These five fictional characters have strongly influenced me, and I will always be grateful to the brilliant people who created them. I am presenting them in chronological order — using the time when this influence started, rather than their date of creation.

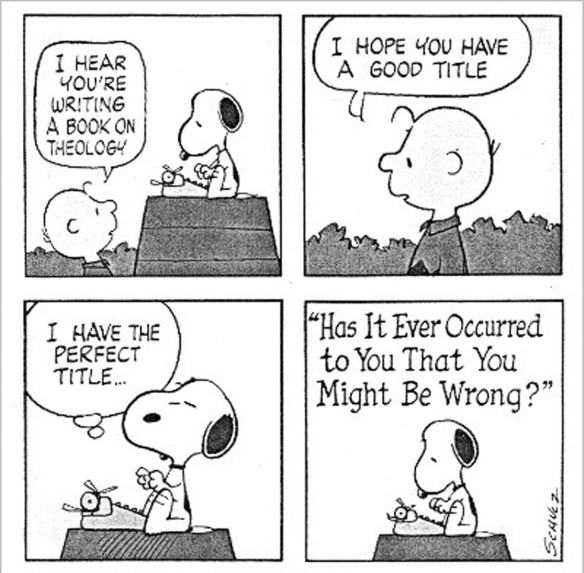

#1: Snoopy

When I was very young — before my memory-record begins, actually — I was given Peanuts books. They were simply left in my possession, as far as I know; no explanation was necessary. The antics of Snoopy, in particular, were extremely entertaining to the little-kid version of me. Since I could see Snoopy dancing around, playing baseball, typing, irritating Lucy, etc., I wanted to understand what was actually going on with all this activity — and this provided the necessary motivation for me to teach myself how to read. There wasn’t any other way for me to tell what was going on in these comic strips!

The fact that I learned to read in this manner led to some very funny moments, due to the fact that the number of words whose meaning I understood, generally from context, exceeded the number of words I knew how to pronounce — and, no doubt, still does. Once, in elementary school, I was laughed at by an entire class, after saying something about the “Eeffel Tower” (yes, that’s how I pronounced it). I also remember pronouncing the “b” in “doubt,” much to the amusement of my parents. Even in graduate school, I made a history professor groan in agony when I made a reference to the Weimar Republic — and pronounced the “W” as it is pronounced in English, rather than German.

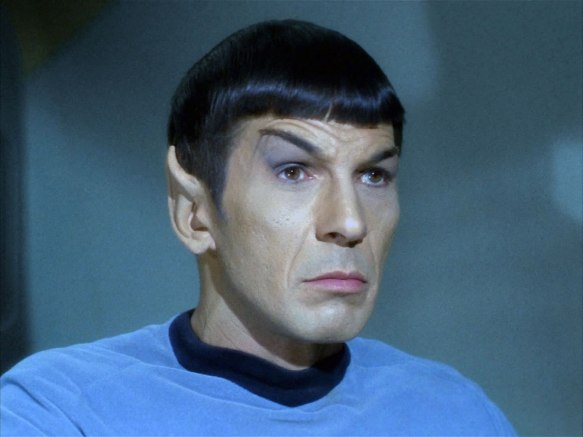

#2: Mr. Spock

A scientist aboard a starship, exploring the galaxy, who uses logic to try to understand two things: the nature of the universe (much of which he understood), and the behavior of illogical humans (something which confuses me to this day, just as it often confounded him). The first person I remember seeing on television had pointed ears, and there were several of them in that episode, “Amok Time.” In other episodes, of course, few Vulcans other than Mr. Spock appeared, and I always found him, to use one of his favorite words, “fascinating.” He influenced me in several ways, and still does, to this day. I am grateful to the creators of this character for inspiring my passion for science, ability to use logic, appreciation of diversity, and strong desire to maintain control of my emotions.

#3: Matt Murdock / Daredevil

I may not have red hair, but I share many other characteristics with Daredevil — and I mean the character from comic books, not that disappointing B-movie (which deserves no further mention). Other than amplified senses — which I experience (unpleasantly) when I get migraines — Daredevil has no superpowers, yet he faces, and does battle with, super-powered villains, and usually wins. He is also a study in contradictions: a lapsed Catholic, who spends a lot of time dressed in a devil costume; a lawyer, with a second “career” as a costumed vigilante; and a blind man, who nonetheless perceives the world around him more clearly than anyone else. Matt Murdock has inspired me to respect the concept of justice, has influenced me to study what laws I need to understand, and, most importantly, has shown me, by example, how to face down those who would do harm to those I care about — and do it, as Daredevil does, without fear. I have also developed my “never give up” attitude, toward my adversaries (bullies, mostly), with inspiration from this character.

Matt Murdock and I have also had very rocky histories when it comes to romantic relationships. I have (finally) found happiness in this aspect of life, and am writing this next to my beloved, sleeping wife. Unfortunately, the writers of Daredevil, while they will let Matt Murdock enjoy temporary happiness in relationships with women, will never allow him to keep it.

#4: Data

Data is amazing to me: a sentient android, and an artificial person. He actually had to go on trial to assert his rights to personhood, and, with the aid of Captain Picard, won the case. He has a lightning-speed calculator, built right in to his positronic brain, which far exceeds the abilities of my own, not-too-shabby mental calculator. I have long had the ambition to gain the ability to reprogram my own brain’s “software,” and have written, on this blog, about how I finally gained that ability, after working on developing it for roughly thirty years. Data, of course, had this ability from the moment he was activated, but, unlike me, he does not have to sleep for it to work.

Despite his claim to experience no emotions, Data often expressed a feeling of being perpetually alone, for there was no one else like him anywhere — until he met his brother, another android, who turned out to be malicious. That feeling of being unlike everyone else is quite familiar to me.

Both Data, and Mr. Spock, display many characteristics of Asperger’s Syndrome, and my study of these two characters helped me figure out that I am, myself, an “Aspie” — our nickname for ourselves.

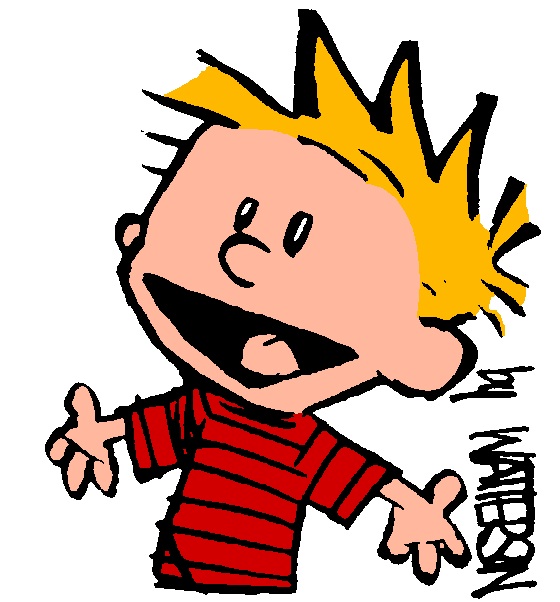

#5: Calvin

When I am playing (and, yes, I play a lot, especially with mathematics), and someone asks me why I, an adult, am playing, I have a standard reply: “Because I’m six.” This is a reference to Calvin, who was six years old during the entire ten-year run of Calvin and Hobbes, the best comic strip ever created. I read it from the first day it appeared in newspapers, and have the boxed set of the complete collection of these comic strips only a meter away, as I write this. Calvin is a six-year old prodigy, as one can tell from his expansive vocabulary, but is prone to making social errors, due to a lack of understanding of social conventions — and both of these things mirror my own life. (I grew up, literally, in science laboratories, unsupervised for hours at a time, designing and conducting my own experiments, and that sort of thing simply doesn’t happen without having profound effects on a child’s development — but, then again, why would I want to be normal?) Calvin, like myself, found elementary school boring in the extreme, and so he slipped, frequently, into his own inner life of fantasy. The fact that, being socially isolated (no siblings, and no friends, other than his stuffed tiger), he is usually alone, never stopped Calvin from having fun. Just like Calvin, I can have unlimited fun, in solitude — because I choose to be this way. Some adults lose the child within them, but, thanks to Calvin’s inspiration, that will never happen to me. I’m actually 46 years old now — so I’m pretty sure that, if I was ever going to lose the ability to have fun, it would have happened already.

To those brilliant people who invented these five characters: thank you.