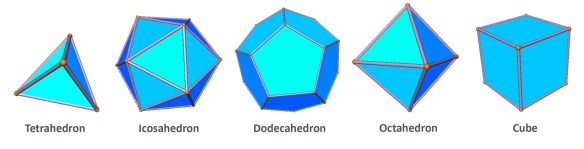

Consider all possible convex polyhedra which have regular polygons as faces. Remove from this set the five Platonic Solids:

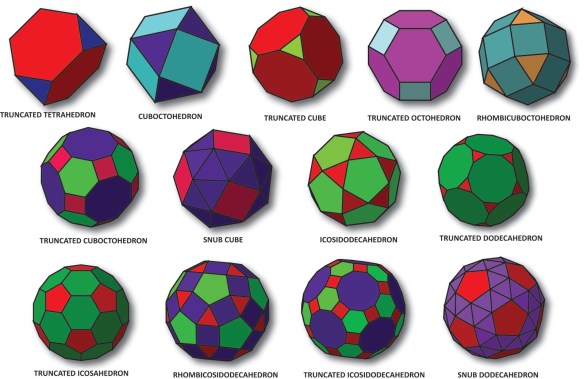

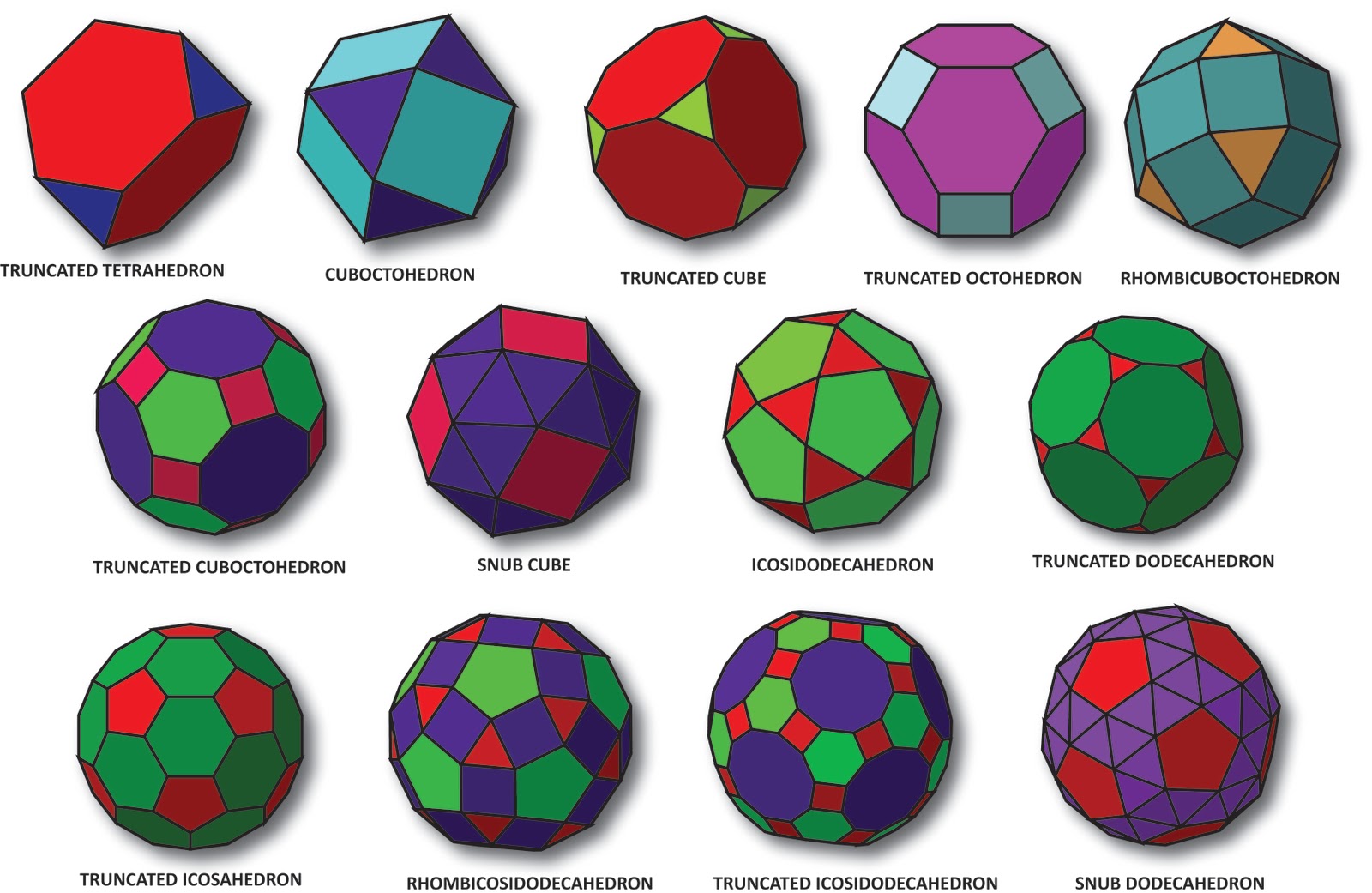

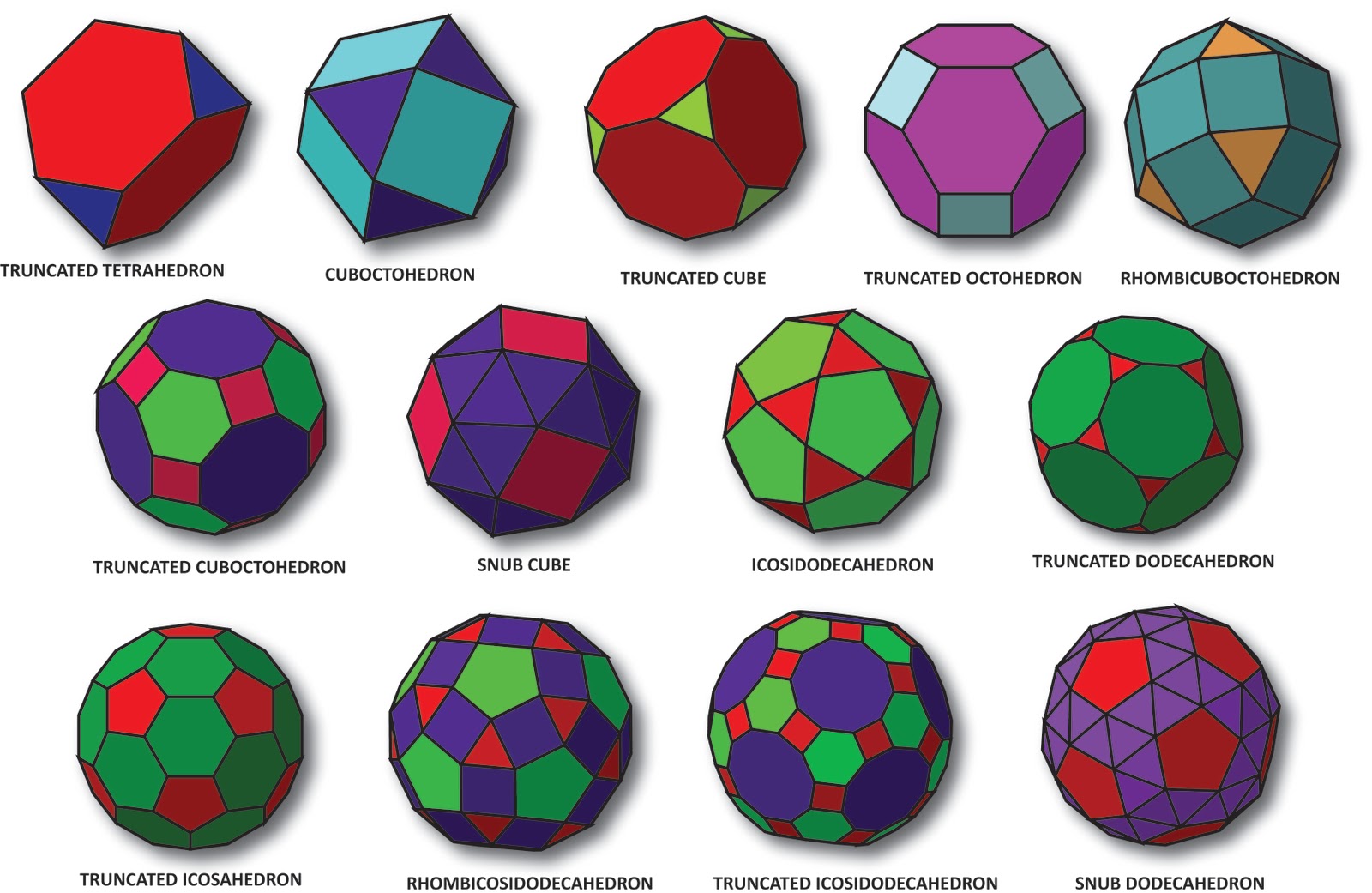

Next, remove the thirteen Archimedean Solids:

Now remove the infinite sets of prisms and antiprisms, the beginning of which are shown here:

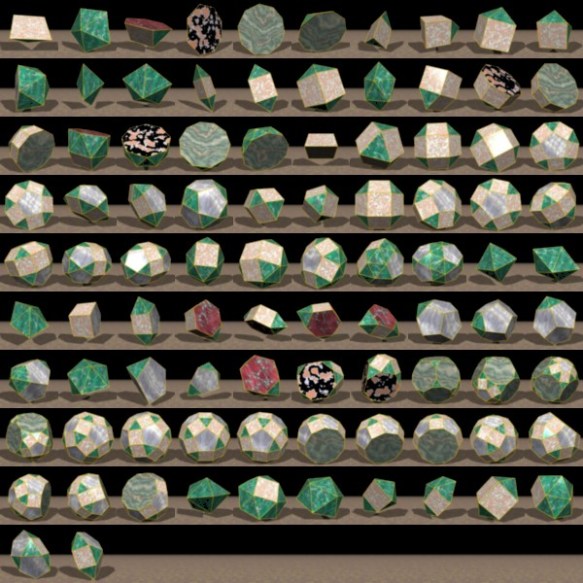

What’s left? The answer to this question is known; it’s the set of Johnson Solids. It has been proven that there are exactly 92 of them:

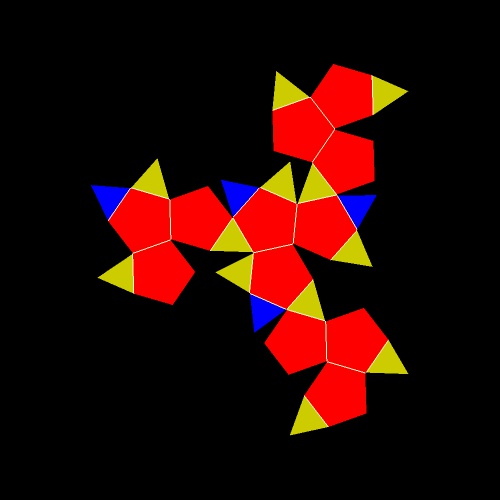

When Norman Johnson systematically found all of these, and named them, in the late 1960s, he found a number of other polyhedra which were extremely close to being in this set. These are called the “near misses.” An example of a near-miss is the tetrated dodecahedron:

If you go to http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php, you can download a free trial version of software, Stella 4d, written by a friend of mine, Robert Webb, which I used to generate this last image. This program has a built-in library of near-misses . . . but it doesn’t have all of them.

Well, why not? The reason is simple: the near-misses have no precise definition. They are simply “almost,” but not quite, Johnson Solids. In the case of the tetrated dodecahedron, what keeps it from being a Johnson Solid is the edges where yellow triangles meet other yellow triangles. These edges must be ~7% longer than the other edges, so the yellow triangles, unlike the other faces, are not quite regular — merely close.

There is no way to justify an arbitrary rule for just how close a near-miss must be to “Johnsonhood” be considered an “official” near-miss, so mathematicians have made no such rule. Research to find more near-misses is ongoing, and, due to the “fuzziness” of the definition, may never stop.

I’ve played a small part in such research, myself. I’ve also been asked how much I’ve been paid for doing this work, but that question misses the point. I’ve collected no money from this, and nobody gets involved in such research in order to get rich. Those of us who do such things are motivated by the desire to have fun through indulgence of mathematical curiosity. Our reward is the pure enjoyment of trying to figure things out, and, on really good days, actually doing so.

I’m having a good day. I’m looking at the Johnson Solids in a different way, purely for fun. I have found something that may be a blind alley, but, if my fellow geometricians show me that it is, that won’t erase the fun I have already had.

Here’s what I have found today. It is not a near-miss in the same way as the tetrated dodecahedron, but is related to the Johnson Solids in a different way. Other than a “heptadecahedron” (for its seventeen faces) it has no name, as of yet:

How is this different from traditional near-misses? Please examine the net (third image). In this heptadecahedron, all of these triangles, pentagons, and the one decagon are perfectly regular, unlike the situation with traditional near-misses. However, some faces, as you can see in the 3-d model, are made of multiple, coplanar equilateral triangles, joined together. In the blue faces, two such triangles form a rhombus; in the yellow faces, three such triangles form an isosceles trapezoid. Since they are coplanar and adjacent, they are one face each, not two, nor three. The dashed lines are not folded in the 3-d model, but merely show where the equilateral triangles are.

Traditional near-misses involve relaxation of the rules for Johnson Solids to permit polyhedra with not-quite-regular faces to join a new “club.”

Well, this heptadecahedron is in a different “club.” To join it, a polyhedron must fit the criteria for “Johnsonhood,” except that some faces may be formed by amalgamation of multiple, coplanar regular polygons.

My current subject of speculation is this: would this new club have an infinite or a finite number of members? If finite, it will, I think, be a larger number than 92. If finite, it will also be a more interesting topic to study.

I don’t know, yet, what answer this new problem has. I do know I am having fun, though. Also known: no one will pay me for this. No one needs to, either.