I’m sure I’ll get back to virtual polyhedra soon enough, but, in the meantime, enjoy this icosidodecahedron made using the traditional Euclidean tools, plus scissors, card stock, and tape. No computers were used to make this polyhedron.

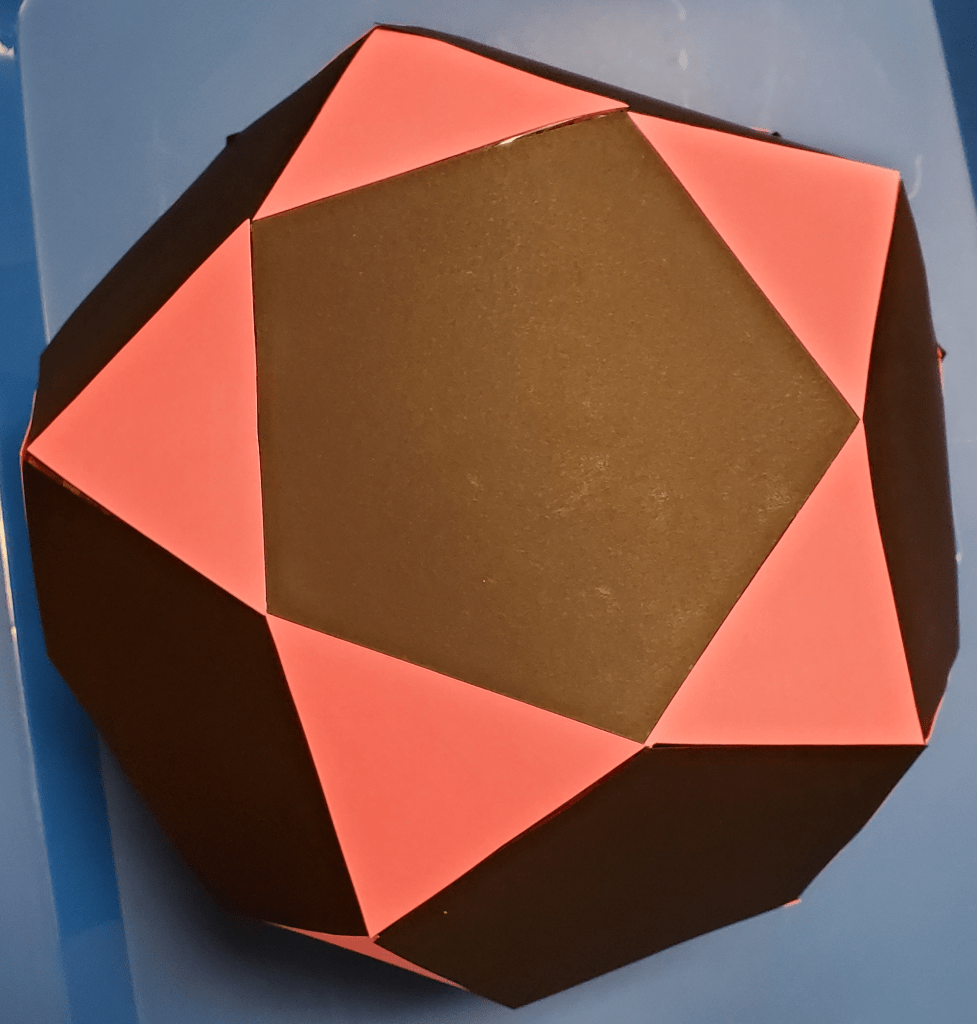

The obtuse triangles here are golden gnomons, which are isosceles triangles with vertex angles of 108 degrees, as well as base-to-leg ratios which are golden. These triangles are facelets; the actual, much larger faces are the regular pentagons of which the golden gnomons are parts. In this model, all facelets which are part of the same (or parallel) faces are all one color, with six colors of paper used, in all, for this non-convex, twelve-faced, regular polyhedron, which is one of the Kepler-Poinsot solids.

Much of each face is hidden from view in this polyhedron’s interior — or rather, this is the case for the mathematical construct called the great dodecahedron. This physical model, on the other hand, is hollow on the inside. One is made only of ideas, while the other is made of atoms.

No computer programs were involved in the construction of this model. It was made using compass, straight edge, scissors, card stock, pencils, and tape.

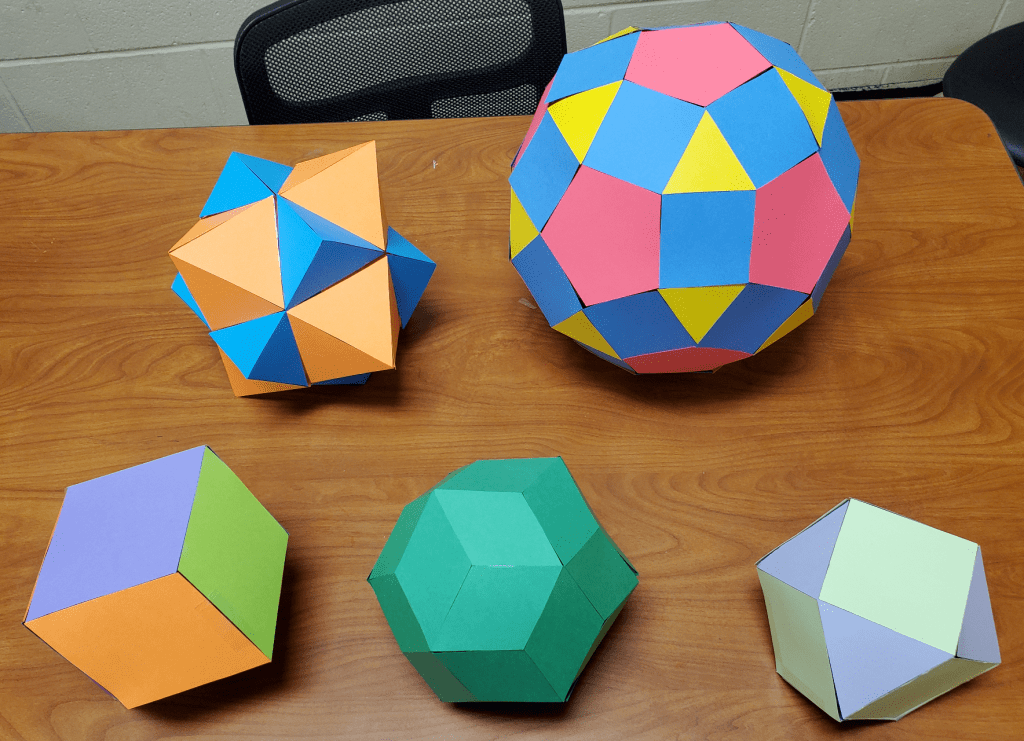

Clockwise from bottom right, these polyhedra are the cuboctahedron, the rhombic triacontahedron, the rhombic dodecahedron, the compound of the cube and the octahedron, and the rhombicosidodecahedron. They were made using card stock, compass, straightedge, scissors, and tape. Since I started blogging polyhedra, I’ve made most of my models using software, and quite a few using Zome. Making paper models was something I used to do . . . until a couple of days ago, when, on a lark, I made the cuboctahedron you see here. Bitten by the bug, I then made the other four models yesterday and today. There’s something satisfying about returning to the basics now and then.

At 53, I’m old enough to have needed a typewriter to write papers, as an undergraduate, back when I was still living with my mother in Little Rock, Arkansas (USA), and attending the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, or UALR. Majoring in history, I wrote many. When I did this, I had a certain ritual about the activity, one that fell from use once I made the much-appreciated transition to using computers, instead.

First, I had to have the typewriter in the center of the living room, oriented at a 45 degree diagonal to the walls. Next, I had to be wearing a bedsheet, wrapped around one shoulder, toga-style. No other clothes were permitted. Finally, I had to have my vinyl version of Mozart’s Requiem playing, over and over, from the time I started the paper until it was completed. This would generally happen early in the morning, on the day the paper was due, procrastination being one of my defining characteristics at that age.

I’m glad I don’t have to write papers anymore, and that the typewriter era is over.