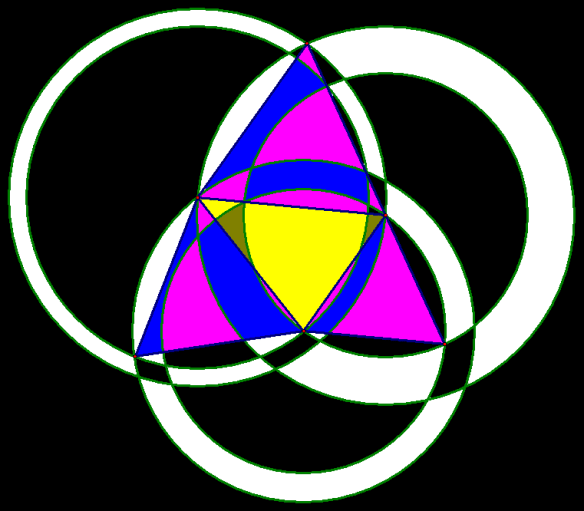

The Ancient Greeks figured out how to combine the Euclidean constructions of the regular pentagon and triangle to obtain constructions for the regular pentadecagon, which has central angles (between adjacent radii) of 360/15 = 24 degrees. Here’s an example, showing how this can be performed:

Also, it’s easy to construct an equilateral triangle, and then bisect an angle of it, to obtain a 30 degree angle.

The existence of angle difference identities in trigonometry is tied to the fact that you can subtract angles, on paper, with Euclidean constructions. Therefore, an angle of 24 degrees may be subtracted from a 30 degree angle to obtain a 6 degree angle. This can be bisected to get a 3 degree angle, and then bisected again to obtain a 1.5 degree angle, then a 0.75 degree angle, and so on.

However, a one degree angle is impossible to construct. Were this not the case, a 24 degree angle’s constructibility would imply that of the 23 degree angle, by subtraction of a one degree angle. After that, subtract three degrees more, and you have a 20 degree angle . . . and with that, you can construct a regular enneagon, also known an a nonagon. But we know — it has been proven — that regular enneagons have no valid Euclidean constructions. Therefore, one degree angles are also non-constructible, by reductio ad absurdam.

Carl Friedrich Gauss’s much more recent proof (1796; he was 19 years old) that a regular polygon of 17 sides can also be constructed — the first significant advance in this field since the time of the ancient Greeks — adds more constructible angles. Building on his work, other mathematicians have also shown that regular polygons with 257 and 65,537 sides can also be constructed, adding yet more constructible angles, but they are all for angles measuring fractional numbers of degrees, since none of these numbers are factors of 360, which equals (2³)(3²)(5). It’s also possible to combine these possible constructions to construct more regular polygons, as was shown above for the pentadecagon. For example, one can construct a regular pentagon with 51 sides, since 51 = (17)(3) — but, again, combinations of this type only lead to possible constructions of angles with measures which are fractional numbers of degrees. For angles with degree measures which are integers, it’s multiples of three — and that’s it.

[Note regarding images: the photograph of a compass at the top of this page was not taken by me, but simply found with a Google image-search. The pentadecagon-construction image, though, I did make, using both Geometer’s Sketchpad and MS-Paint.]