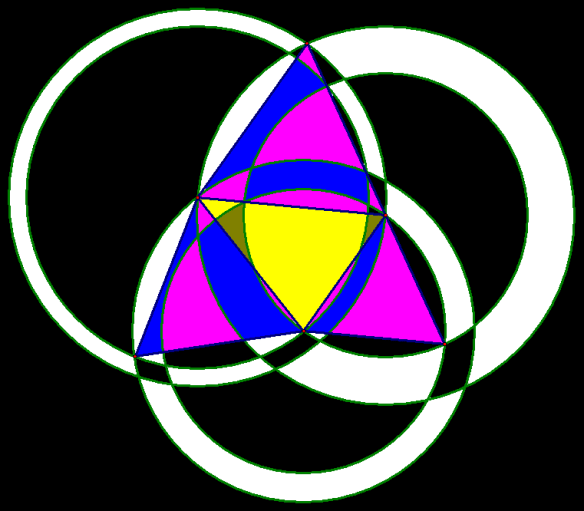

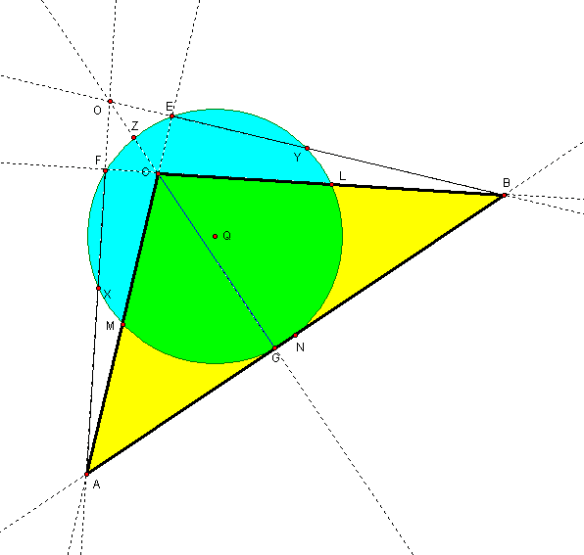

In this diagram, the original triangle is ABC, and is yellow. The brown line, u, is that triangle’s Euler Line, which contains the triangle’s orthocenter (O), circumcenter (K), centroid (R), and nine-point circle center (circle shown, centered at Q). The point I have found on the Euler Line is at W.

To find W, do the following: reflect triangle ABC over the Euler Line to form triangle A’B’C’ (shown uncolored, and with thick black edges). Both triangles, ABC and A’B’C’, have the same circumcircle (shown in green, with uncolored interior). Because of this, a cyclic hexagon may be formed by joining A, A’, B, B’, C, and C’ with segments, linking each in turn as one encounters them on a mental trip once around this circumcircle (the order in which these six points are encountered can change as A, B, and/or C are moved).

A hexagon has 9 diagonals. Of these, six are the sides of ABC and A’B’C’. Here, they are shown in black, and the other three diagonals are shown in red. These red diagonals are not necessarily concurrent, but any two of them do have to intersect, and those three intersections are points T, V, and W. At least one of those points — W, in this case — must be on the Euler Line. To get the other two points on the Euler Line, make the triangle approach regularity. As this is done, K, R, Q, O, and W converge, making the definition of the Euler Line itself problematical.

Point W needs a better definition. Which two of the three hexagon-diagonals which aren’t sides of the original triangle, nor its reflection, intersect on the Euler Line? I haven’t figured that out yet. Also, a formal proof for most of what I have described here is beyond my present abilities.

Why, then, do I believe the statements to be true? Answer: the evidence provided by experiment. This image is a screenshot from Geometer’s Sketchpad — but I don’t know how to post an animation of what happens when A, B, or C are moved. However, I can move them myself, with the program in operation, and observe how everything changes (this is one of the best features of Sketchpad, in my opinion). As these points are moved around, pairs of the heavy red segments (hexagon sides, and three of its diagonals) sometimes “flip” — a side becomes a diagonal, and that diagonal becomes a side. At that point, T, V, and W must be relabeled. Also, some positions of A, B, and C make the area of triangle TVW approaches zero — it collapses to a point on the Euler Line.

Odd things also happen if you make triangle ABC isosceles, because the Euler Line for an isosceles triangle is the perpendicular bisector of the base, which causes triangle A’B’C’, upon reflection of triangle ABC across the Euler Line, to map onto triangle ABC. When this happens, the hexagon becomes a single triangle, making its diagonals vanish — and point W goes and “hides” at the vertex opposite the base of isosceles triangle ABC, by which I mean W approaches that vertex as scalene triangles get closer to being isosceles.

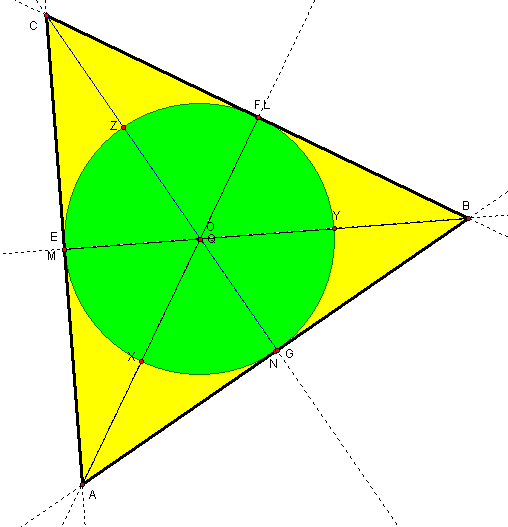

Also, things change a bit if triangle ABC is obtuse:

The Nagel Line (that line which contains the incenter, S, and the centroid, R, where it intersects the Euler Line) has been added, and is shown in purple. As you can see, point W is not on the Nagel Line. With the triangle being obtuse, the earlier all-red convex hexagon is now gone, because two of its sides are black, due to them being sides of triangles ABC and A’B’C’. Point W persists, though, still on the Euler Line, and located in the area between the vertices of these two triangles’ obtuse angles. My hope, in pointing this last fact out, is that it might help define which two hexagon-diagonals’ intersection defines the location of W. It might also be possible to use this to distinguish between the first diagram’s points T, V, and W, for, in the first diagram, W, which is what I am calling the only one of these three points to be on the Euler Line, was the one nearest the largest interior angle of triangle ABC — and the same is also true of triangle A’B’C’, as well. However, the matter of picking W out of the “T, V, and W” set of points may have nothing to do with angle size — it could be, instead, a matter of proximity of A, B, and C, as well as their reflections, to the Euler Line itself. In other words, “Which one is W?” might be answerable simply by examination of which member of the “T, V, and W” set is closest to the member of the set “A, B, and C,” as well as “A’, B’, and C’,” which is, itself, closest to the Euler Line. This matter needs further investigation, with which I would welcome help from anyone.

Also: there are two easier-to-define points on the Euler Line, unlabeled in the diagrams above, which are the two points where triangles ABC and A’B’C’ intersect. The existence of these points on the Euler Line is simply a consequence of the fact that A’B’C’ was formed by reflecting the original triangle over the Euler Line. These two points could use special names, but nothing is immediately springing to my mind which would be appropriate. Another point on the Euler Line, also a consequence of reflection, appears as the midpoint of segment TV in the first diagram, and the midpoint of BB’ in the second — segments which appear analogous. This also seems to apply to the midpoints of AA’ and CC’. At this stage of the discovery process, though, appearances can be misleading.

I want to work out a better definition for this point, W, on the Euler Line, perhaps as an as-yet-undiscovered member of the large collection of triangle centers. I also need to know if it has already been found. If you have information pertinent either of these things, or to any part of this post, please leave it here, in a comment.