It’s important to explain, right up front, that Ronald Reagan was president when I last took calculus. However, I have a new determination to learn the subject. I have a hunch this may go better without the “help” of actually being enrolled in a calculus class, since the way I learn things, and the way most people learn things, aren’t much alike.

My current calculus puzzle started when I noticed that taking the derivative of the volume of a sphere, in terms of the radius, (4/3)πr³, yields the formula for the surface area of a sphere, 4πr². That was both unexpected and exciting, so I tried applying the same idea to another solid: the cube. With edge length e, the volume of a cube is e³, and the derivative of that is 3e² . . . but that’s only half of the surface area of a cube, which is 6e².

Half? What’s going on here? I mentioned this puzzle on Facebook, where I have many on my friends’-list whose mathematical knowledge exceeds my own. It was pointed out to me that I’d made an important and unhelpful change by going from using the radius, for the sphere, to the edge length, for the cube.

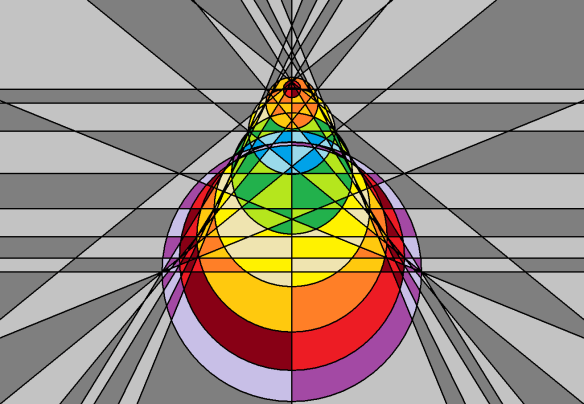

So I’ll try this again, but do it in terms of the radius of the cube, rather than the edge length. For a cube, the radius extends from the center to any of the cube’s eight vertices. Both the light and dark blue segments in the diagram below are cube radii.

This radius is sqrt(3)/2 times the cube’s edge length, as can be verified by applying the Pythagorean Theorem twice, first to triangle ABC (which shows that the green face-diagonal is sqrt(2) times the edge length), and then to triangle BCD (which yields sqrt(3) times the edge length for the interior diagonal DC, half of which is the radius).

It then follows that, if r = [sqrt(3)/2]e, that e = [2/sqrt(3)]r, which “cleans up” to e = (2/3)sqrt(3)r, when the denominator is rationalized.

If a cube’s volume is e³, and e = (2/3)sqrt(3)r, it then follows that V = [(2/3)sqrt(3)r]³ = (8/27)(3)sqrt(3)r³ = (24/27)sqrt(3)r³ = [8sqrt(3)/9]r³. If I take the derivative of the last expression, I get [8sqrt(3)/3]r² for the derivative of the volume, which I now need to compare to the surface area of a cube, in terms of its radius, rather than edge length.

So here goes . . . SA = 6e² = 6[(2/3)sqrt(3)r]² = [48(3)/9]r² = 16r², which isn’t what I got for the derivative of the volume, above.

Well, I was using, as the radius, the radius of the cube’s circumscribed sphere. Perhaps I should have used the inscribed sphere, instead? The radius of the cube’s inscribed sphere is the “invisible” segment FM in the diagram above, which I’m going to call “a” (for “apothem,” because this looks like the 3-d version of the apothem of a regular polygon). The length of a is exactly one-half that of e, the cube’s edge length, which means that e = 2a. Therefore, V = e³ = (2a)³ = 8a³, the derivative of which is 24a².

Now to check the surface area, in terms of a: SA = 6e² = 6(2a)² = 24a², and that’s what I got when I took the derivative of the volume, in terms of a.

So this trick works for the cube if you use the radius of the inscribed sphere, but not the circumscribed sphere. This leaves me with three questions to address later:

- Will this also work for other polyhedra? This is something I intend to explore in future blog-posts, starting with the tetrahedron and the octahedron.

- Why did this work at all?

- Why was it necessary to use the radius of the cube’s inscribed sphere, rather than its circumscribed sphere?

If any reader of this post knows the answer(s) to #2 and/or #3, sharing your knowledge in a comment would be very much appreciated.

Here’s what it looks like, when viewed from two other angles.

Here’s what it looks like, when viewed from two other angles.