This pattern could be continued, indefinitely, into space.

Here is a second view, in rainbow color mode, and with all the squares hidden.

[These images were created with Stella 4d, software you may buy — or try for free — right here.]

This pattern could be continued, indefinitely, into space.

Here is a second view, in rainbow color mode, and with all the squares hidden.

[These images were created with Stella 4d, software you may buy — or try for free — right here.]

I have made many posts here using polyhedral augmentation, but what I haven’t done — yet — is explain it. I have also neglected the reciprocal function of augmentation, which is called excavation. It is now time to fix both these problems.

Augmentation is the easier of the two to explain, especially with images. The figure below call be seen as a blue icosahedron augmented, on a single face, by a red-and-yellow icosidodecahedron. It can also be viewed, with equal validity, as the larger figure (the icosidodecahedron) augmented, on a single triangular face, with an icosahedron.

When augmenting an icosidodecahedron with an icosahedron in this manner, one simply attaches the icosahedron to a triangular face of the icosidodecahedron. The reciprocal process, excavation, involves “digging out” one polyhedral shape from the other. Here is what an icosidodecahedron looks like, after having an icosahedron excavated from it, on a single triangular face.

Excavating the smaller polyhedron from the larger one is easier to picture in advance, just as one can imagine what the Earth would look like, if a Moon-sized sphereoid were excavated from it, with a large, round hole making the excavation visible. (This is mathematics, not science, so we’re ignoring the fact that gravity would instantly cause the collapse of such a compound planetary object, with dire consequences for all inhabitants.) What’s more difficult is picturing what would result if this were turned around, and the Earth was used to excavate the Moon.

This “Earth-excavated Moon” idea is analogous to excavating the larger icosidodecahedron from the smaller icosahedron. If one thinks of subtracting the volume of one solid from that of the other, such a creature should have negative volume — except, of course, that this makes no sense, which is consistent with the fact that it would be impossible to do such a thing with physical objects: there isn’t enough matter in the Moon to remove an Earth’s worth of matter from the Moon. Also, moving back to polyhedra, with excavation only into a single face, it turns out that there is no change in appearance when the excavation-order is reversed:

(Well, OK, there was a small change in appearance between the two images, but that’s only because I changed the viewing angle a bit, to give you a better view of the blue faces.)

Things get different — and the augmentation- and excavation-orders begin to matter a lot more — when these operations are performed on all available faces at once, which, in this case, means on all twenty of each polyhedron’s triangular faces. Here is the easiest case to visualize: an icosidodecahedron, augmented by twenty icosahedra.

If you use the reciprocal function, excavation, but leave the order of polyhedra the same, you get a central icosidodecahedron, excavated by twenty smaller, intersecting icosahedra:

It is, of course, possible to have other combinations. The ones I find most interesting, using these two polyhedra, are “global” augmentation and excavation of the smaller figure, the icosahedron, by twenty of the larger ones, the icosidodecahedra. Why? Simple: putting the icosidodecahedra on the outside allows for maximum visibility of both pentagons and triangles. On the other hand, the central icosahedron is completely hidden from view, whether augmentation or excavation is used. Here is the augmentation case, or what I have called a “cluster” polyhedron, many varieties of which can be seen elsewhere on this blog (just search for “cluster,” or “cluster polyhedron,” to find them):

The global-excavation case which has the icosahedron hidden in the middle is similar to the cluster immediately above, in that all that can be seen are twenty intersecting icosidodecahedra. However, it also varies noticeably, because, with excavation, the icosidodecahedra are closer to the center of the entire cluster (the invisible, central icosahedron’s center) than was the case with augmentation. The last image here is of an invisible, central icosahedron, with an icosidodecahedron excavated from all twenty triangular faces. The larger polyhedra “punch through” the smaller one from all sides at once, trapping the central polyhedron — the blue icosahedron — from view. The remaining object looks, to me at least, more like a faceted icosidodecahedron than a cluster-polyhedron. I am of the opinion, but have not verified, that this resemblance to a faceting of the icosidodecahedron is illusory.

[Image credits: all images in this post were made using Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator. This program may be purchased, or tried as a free trial download, at http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php.]

I found both of these with what one could call “random-walk playing” with polyhedral-manipulation software, Stella 4d, available here, with a free trial-download available. In the figure above, both compound components are skewed cubes, while the image below shows a compound of three skewed tetrahedra. Since (2)(6) = (3)(4) = 12, each of these compounds has the same total number of faces, although, of course, the number of faces per component polyhedron varies from one compound to the other.

Many commercial products are available to model polyhedra, such as Zometools, Stella 4d, Polydrons, Astro-Logix, and magnetic spheres which can be assembled into polyhedral shapes, sometimes with brightly-colored struts for the edges of the polyhedron. The first three tools, I can recommend without reservation (and I simply haven’t tried Astro-Logix, yet), but there is a problem with using rare-earth “ball magnets” to model polyhedra: the magnets don’t last long, for, while their magnetic fields are powerful, the neodymium-iron-boron alloy used to make these magnets is not durable, and such spherical magnets break easily.

For this reason, I decided to try a variation of the “ball magnet” idea, and instead obtained some (non-magnetic) steel balls, along with small, cylindrical rare-earth magnets to go between them, thus serving as polyhedral edges, while the steel balls serve as polyhedral vertices. With the steel balls keeping these cylindrical magnets separated (rather than smashing into each other), the magnets are more durable, and the steel balls, of course, do not have a durability problem. Here’s what I was able to produce when I attempted to make a set of Platonic solids, using this method:

The icosahedron, cube, octahedron, and tetrahedron shown above were easy to make, but attempting to construct a dodecahedron from these materials was an exercise in frustration. Forming one pentagon of this type is easy, but pentagons of this type lack the rigidity of triangles, or even the lesser rigidity of squares, and I was never able to get twelve such pentagons formed into a dodecahedron without the whole thing collapsing into a big ferromagnetic glob, which isn’t what I wanted at all.

Every polyhedron-modeling system has advantages and disadvantages, and the weakness of this particular system was made apparent by my failed attempt to construct a dodecahedron. I next tried adding triangles to pentagons, hoping the rigidity of the triangles would stabilize the pentagons, and allow me to construct an icosidodecahedron, the Archimedean solid which combines the twenty triangles of an icosahedron with the twelve pentagons of a dodecahedron. This method of combining triangles with pentagons did work, and I was able to construct an icosidodecahedron.

A major advantage of this medium for polyhedral modeling is that it is incredibly economical, compared to most specialized-purpose polyhedron-building tools. The materials are readily available on eBay. Non-magnetized steel balls are much less expensive than their magnetic counterparts; also, small cylindrical magnets are inexpensive as well, especially in large quantities. These will not be the last polyhedra I build using these materials — but they are suited for certain polyhedra, more so than others. With this system, the more equilateral triangles a given polyhedron has as faces, the better, for the rigidity of triangles adds to the overall stability of triangle-containing polyhedral models.

One of my early introductions to polyhedra came through playing the game Advanced Dungeons and Dragons (AD&D), which uses a standard seven-die set which includes the five Platonic Solids, plus two “d10s” (either ten-faced dipyramids or trapezohedra) which are used as a pair to generate random numbers from 1 to 100.

Assuming they are made with uniform density, these polyhedral dice are all “fair dice” — meaning that, for example, the d12 at the top of the picture has an equal chance of rolling any of 12 results, every time it is rolled.

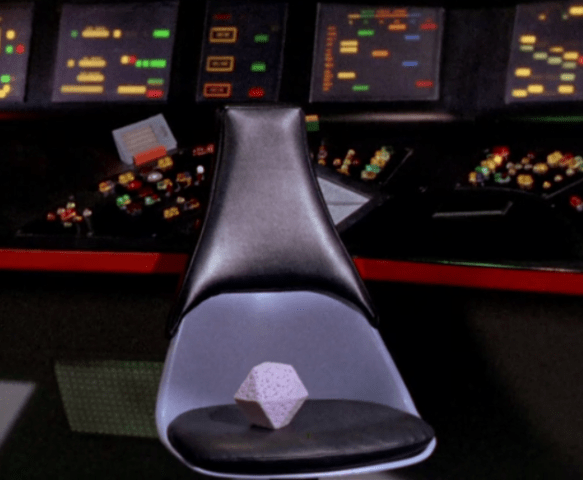

I had also encountered, even earlier, a polyhedron which I believed (correctly) would not work as a fair die, since there is no reason to assume that rolling a cuboctahedron would result in equal probabilities for each face, given that some of the faces are squares, while others are triangles. This shape was familiar to me long before I heard (or even read) the word “cuboctahedron,” though, because I learned about it while watching “By Any Other Name,” an episode of the original Star Trek television series. At no point in this episode is the word “cuboctahedron” used, even though the entire crew of the USS Enterprise (with four exceptions) spend most of the episode in cuboctahedral form, as Lt. Uhura appears, at her bridge station, in this screenshot:

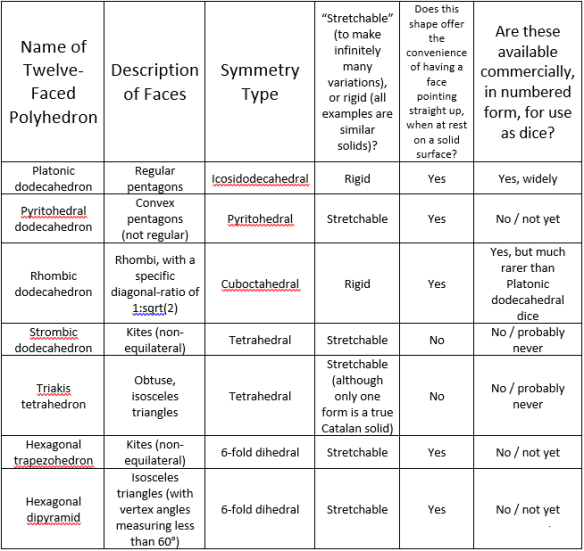

When examining uniform-density polyhedra to look for “fair dice,” therefore, one of the first things I look for is isohedrality — all faces must have the same shape, unlike the case of the cuboctahedron, but like the cases of AD&D dice. The next thing I examine is symmetry, hoping to find that a particular polyhedron’s symmetry gives no probability-advantage to any face(s). With these two tests in mind, I decided to see how many different fair, dodecahedral d12s I could find, including polyhedra which could work, whether or not such shapes had actually been used as real dice, at any time, by anyone.

When looking for dodecahedral “fair dice,” anyone with a familiarity with AD&D, or polyhedra, is likely to identify, first, the one with this shape:

The word “dodecahedron” literally refers simply to any polyhedra with twelve faces, but, in practice, most references to dodecahedra concern this twelve-faced polyhedron — the one found immediately above, and at the top of the photograph of a standard set of AD&D dice. When it is necessary to distinguish it from other twelve-faced polyhedra, this can be called, instead, the “Platonic dodecahedron.” It is the only dodecahedron to be both regular and convex; it also possesses icosidodecahedral symmetry, also known as icosahedral symmetry.

Although the pentagons in the Platonic dodecahedron are regular, it is also possible to make a fair-die polyhedron with irregular pentagons. Such a shape appears, occasionally, in the mineral pyrite, or FeS2, explaining the origin of the term “pyritohedral symmetry,” which is the symmetry-type of this particular dodecahedron: the pyritohedral dodecahedron.

There are actually an infinite number of slightly-different pyritohedral dodecahedra, as one can easily picture, by imagining a change in the length of the longest edges in the image directly above. However, for purposes of this survey, all possible pyritohedral dodecahedra are viewed as a single answer — the second, after the Platonic dodecahedron — to the question, “Which twelve-faced polyhedra would work as ‘fair dice?'”

The third answer to this question is provided by a completely different polyhedron, rather than a “warping” of the Platonic dodecahedron. In this third dodecahedron, the faces are rhombi, explaining why it is called the rhombic dodecahedron. Johannes Kepler studied this polyhedron extensively. Not just any rhombus will work, as a face, to make this polyhedron; it must be a specific type — one with diagonal-lengths in a ratio of one, to the square root of two.

This particular “fair die” occurs in nature, as crystals of the mineral garnet. There are also twelve-sided dice of this type now being sold, although finding them isn’t the easiest thing to do; one such retail outlet (in case you’d like to buy some rhombic dodecahedral dice) is The Dice Lab, which sells such dice at this website.

The rhombic dodecahedron, unlike the other dodecahedra shown above or below, has cuboctahedral symmetry, also known as octahedral symmetry. It is also the dual of the cuboctahedron — the same polyhedron about which I first learned as a young child, watching Star Trek.

Just as the first solution to this twelve-faced “fair dice” quest (the Platonic dodecahedron) can be “stretched” to find a second solution (the pyritohedral dodecahedron), this third solution (the rhombic dodecahedron) can be altered slightly to give a fourth solution, which I call the strombic dodecahedron, although it has other names as well (one, for example, is the “deltoidal dodecahedron”). To make this shape, one keeps the overall pattern of the rhombic dodecahedron, but allows the rhombi to be stretched into non-equilateral kites, as shown here:

As far as I know, no one has actually made such dice — but that doesn’t matter, for the point is that such dice could be made, and would be fair, given uniform density. This is actually a family of possible solutions, as was the case with the pyritohedral dodecahedron, because different versions of the strombic dodecahedron can be created by varying the length-ratio of the long and short edges of the figure. Such variants would still have the same name and symmetry-type, however, and that symmetry-type is tetrahedral.

At least one other twelve-faced “fair die” can be made which also has tetrahedral symmetry: the Catalan solid known as the triakis tetrahedron, dual of the Archimedean truncated tetrahedron:

The triakis tetrahedron can be viewed as a Platonic tetrahedron, with each of its faces augmented by short, triangular pyramids which have lateral faces which are obtuse, isosceles triangles. The height of these short pyramids can be changed, while still leaving the overall polyhedron convex, over a range of heights; such altered versions, if not true duals of the Archimedean truncated tetrahedron, could simply be called non-Catalan tetrakis tetrahedra. The Catalan (and various convex non-Catalan) tetrakis tetrahedra are here collectively offered as the fifth type of twelve-faced polyhedra which can serve as fair dice.

The fourth and fifth solutions do have a problem, due to their tetrahedral symmetry: as a physical die, when rolled on a horizontal surface, the various strombic dodecahedra and triakis tetrahedra would land without a face pointing straight up, since they do not have parallel faces. This, however, merely means that, as fair dice, they wouldn’t be as convenient as the others; one might, for example, number their faces, and then pick up the die after it is rolled, to see which number ended up pointing straight down, rather than straight up. Other “workarounds” could also be devised. The need for such extra work, however, does not negate the fact that these polyhedra can be used as fair dice, for the problem was not set up with a convenience-requirement.

Further examination of a standard seven-piece AD&D dice set can lead to still more “fair d12s,” due to the presence of the d10s, also known, when used in pairs, as percentile dice. Most AD&D d10s have kites as faces (as seen in the metal dice set above), and are duals of pentagonal antiprisms, and so are themselves known as pentagonal trapezohedra (also known as “pentagonal deltohedra,” among other names). To get a similar fair die with twelve faces, rather than ten, one can simply start with a hexagonal antiprism, and then examine its dual: the hexagonal trapezohedron, which has six-fold dihedral symmetry:

By varying the long-to-short edge length ratio of the kite-faces in this polyhedron, the overall height of this polyhedron, as a function of its width, can be changed. This sixth solution is, therefore, another “infinite family” solution — as is the seventh solution, shown below, which can be easily made from the sixth solution (immediately above). To do so, mentally hold in place the bottom half of the hexagonal trapezohedra — but let the top half rotate for another 1/12 of a rotation before also “freezing” it. There is no need, now, for the zig-zagging “equator” in the polyhedron seen above — it can now be replaced with the coplanar edges of a hexagon, hidden inside the polyhedron, with the result that the twelve kites are replaced by a dozen isosceles triangles, turning the overall shape into a hexagonal dipyramid. These isosceles triangles must have vertex angles which measure less than 60° — in order to keep the figure from collapsing into something with no height, or with many edges which do not meet. Like the sixth solution before it, this seventh solution also has six-fold dihedral symmetry.

Next, here is a table which summarizes information about these seven possible dodecahedral “fair d12s.”

It is important to point out that this collection of seven solutions may not be complete, and I make no claim that it is. In fact, I strongly suspect it is not complete. It is simply the set of all solutions which have occurred to me — so far.

Some may wonder why I did not include the “barrel”-style d12s, which are also commercially available. This omission is no oversight. This particular style of d12 is not actually dodecahedral; it really has more than 12 faces, but is designed in such a way that it only has 12 faces which such dice can land on, and stay on — and that is not the same thing, at all. Also, I’m only looking for d12s here, which is why I did not include the “barrel”-style d4, even though it is a polyhedron which does have twelve faces.

Lastly, of the pictures in this post, the seven which feature rotating polyhedra were created using Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software which may be purchased, or tried for free, at this website.

In the last post here, three different color-versions of the same cluster-polyhedron were shown. Since this cluster-polyhedron is chiral, it is possible to make a compound of it, and its own enantiomer (or “mirror-image,” if you prefer). This first image shows that, with the face-color chosen by the number of sides of each face.

Shown next is the dual of this figure, also colored by the number of sides of each face.

Next, another image of the first compound shown here, but with the colors chosen by face-type (referring to each face’s position in the overall polyhedron).

Finally, here is the dual, again, also with colors chosen by face-type.

All four of these images were generated with Stella 4d, a computer program available at http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php.

This cluster-polyhedron was made with Stella 4d, software you can try at this website. Above, it is colored by face-type, referring to each face’s position within the overall cluster. In the image below, the original compound of five cubes contained one cube each, of five colors, and then each snub cube “inherited” its color from the cube to which it was attached.

In the next version, the colors are chosen by the number of sides of each face.

The rhombic enneacontahedron has thirty faces which are narrow rhombi, and sixty faces which are wider rhombi. It is also known as a vertex-based zonohedrified dodecahedron. To create this cluster-polyhedron, I started with one rhombic enneacontahedron in the center, and then augmented its thirty red faces (the narrow rhombi) with additional rhombic enneacontahedra. In the image above, I kept the yellow color for all the wide rhombi, and red for all the narrow ones. In the next image, however, the rhombi are colored by face type, referring to their position in the entire cluster-polyhedron.

Software credit: I created this using Stella 4d, software you can buy, or try for free, at this website.

The version of the final stellation of the compound of five cubes shown above has its colors derived from the traditional five-color version of the original compound, itself. The one below, by contrast, has its colors selected by face-type, without regard for the original compound.

Both of these virtual models were created with Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software available at this website. Also, for more about this particular polyhedron, please see the next post.

Because the snub dodecahedron is chiral, the polyhedral cluster, above, is also chiral, as only one enantiomer of the snub dodecahedron was used when augmenting the single icosahedron, which is hidden at the center of the cluster.

As is the case with all chiral polyhedra, this cluster can be used to make a compound of itself, and its own enantiomer (or “mirror-image”):

The image above uses the same coloring-scheme as the first image shown in this post. If, however, the two enantiomorphic components are each given a different overall color, this second cluster looks quite different:

All three of these virtual models were created using Stella 4d, software available at this website.