I made this compound using software called Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator. This program may be purchased (or a trial download tried for free) at this website.

Tag Archives: polyhedral

A Central Icosidodecahedron, Augmented with Twenty Cuboctahedra, and Twelve More Icosidodecahedra

Above and below, you will find two different coloring-schemes for this particular cluster of polyhedra. I made both of these rotating images using Stella 4d, software you can buy, or try for free, right here.

A Central Icosahedron, Augmented with Twenty Rhombicosidodecahedra

A model this complex would have taken days to build by hand. With software called Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, however, making this “virtual model” was easy. This program is available for purchase at this website — and there is a free trial download available there, as well.

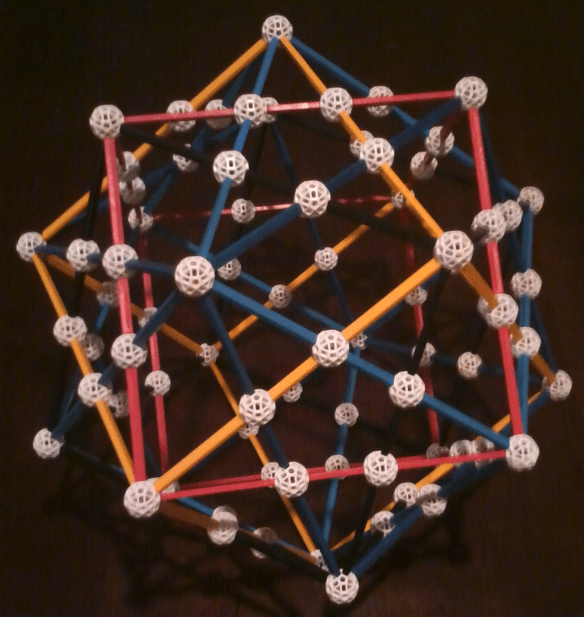

The Compound of Five Cubes, Rendered in Five Colors of Zome

Ordinarily, with Zometools, the compound of five cubes is an all-blue model. However, I wanted to build one in which each cube is a different color, so I made a special request to the Zometool Corporation (their website: http://www.zometool.com) for some off-color parts, to make this possible.

The five colors used in this model are standard blue, a darker shade of blue, red, yellow, and black.

I also received the struts needed to build this model with one cube in white, so I will be making a second version of this soon. I didn’t want the Zomeballs used to match any strut color, though, so I will have to wait for the shipment of purple Zomeballs I ordered, today, to arrive, before I can build that model.

Zome is a fantastic tool to use for mathematical investigations, as well as education, and other applications as well. I recommend this product highly, and without reservation.

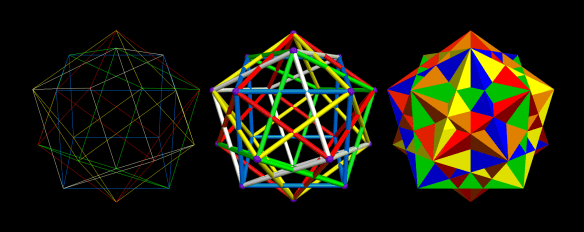

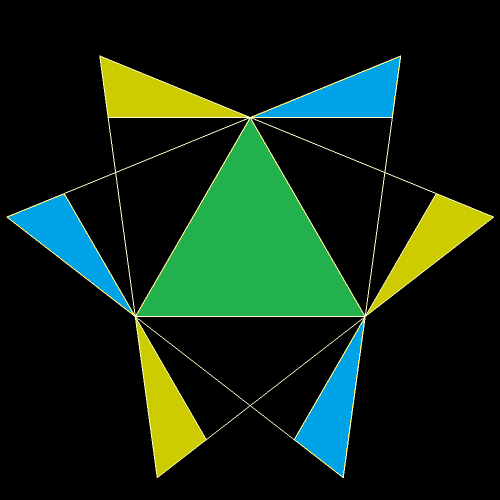

Three Different Depictions of the Compound of Five Cubes

The most common depiction of the compound of five cubes uses solid cubes, each of a different color:

This isn’t the only way to display this compound, though. If the faces of the cubes are hidden, then the interior structure of the compound can be seen. An edges-only depiction, still keeping a separate color for each cube, looks like this:

If these thin edges are then thickened into cylinders, that makes a third way to depict this polyhedral compound. It creates a minor problem, though: edges-as-cylinders looks awful without vertices shown as well, and the best way I have found to depict vertices, in this situation, is with spheres. With vertices shown as spheres, however, a sixth color, only for the vertex-spheres, is needed. Why? Because each vertex is shared by six edges: three from a cube of one color, and three from a second cube, of a different color.

Finally, here are all three versions, side-by-side for comparison, and with the motion stopped.

All images in this post were created using Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software you may try for free at this website.

Various Views of Three Different Polyhedral Compounds: Those of (1) Five Cuboctahedra, (2) Five of Its Dual, the Rhombic Dodecahedron, and (3) Ten Components — Five Each, of Both Polyhedra.

Polyhedral compounds differ in the amount of effort needed to understand their internal structure, as well as the way the compounds’ components are assembled, relative to each other. This compound, the compound of five cuboctahedra, and those related to it, offer challenges not offered by all polyhedral compounds, especially those which are well-known.

The image above (made with Stella 4d, as are others in this post — software available here) is colored in the traditional style for compounds: each of the five cuboctahedra is assigned a color of its own. There’s a problem with this, however, and it is related to the triangular faces, due to the fact that these faces appear in coplanar pairs, each from a different component of the compound.

The yellow regions above are from a triangular face of the yellow component, while the blue regions are from a blue triangular face. The equilateral triangle in the center, being part of both the yellow and blue components, must be assigned a “compromise color” — in this case, green. The necessity of such compromise-colors can make understanding the compound by examination of an image more difficult than it with with, say, the compound of five cubes (not shown, but you can see it here, if you wish). Therefore, I decided to look at this another way: coloring each face of the five-cuboctahedra compound by face type, instead of by component.

Another helpful view may be created by simply hiding all the faces, revealing internal structure which was previously obscured.

Since the dual of the cuboctahedron is the rhombic dodecahedron, the dual of the compound above is the compound of five rhombic dodecahedra, shown, first, colored by giving each component a different color.

A problem with this view is that most of what’s “going on” (in the way the compound is assembled) cannot be seen — it’s hidden inside the figure. An option which helped above (with the five-cuboctahedra compound), coloring by face type, is not nearly as helpful here:

Why wasn’t it helpful? Simple: all sixty faces are of the same type. It can be made more attractive by putting Stella 4d into “rainbow color” mode, but I cannot claim that helps with comprehension of the compound.

With this compound, what’s really needed is a “ball-and-stick” model, with the faces hidden to reveal the compound’s inner structure.

Since the two five-part compounds above are duals, they can also be combined to form a ten-part compound: that of five cuboctahedra and five rhombic dodecahedra. In the first image below, each of the ten components is assigned its own color.

In this ten-part compound, the coloring-problem caused in the first image in this post, coplanar and overlapping triangles of different colors, vanishes, for those regions of overlap are hidden in the ten-part compound’s interior. This is one reason why this coloring-scheme is the one I find the most helpful, for this ten-part compound (unlike the two five-part compounds above). However, so that readers may make this choice for themselves, two other versions are shown below, starting with coloring by face type.

Finally, the hollow version of this ten-part compound. This is only a personal opinion, but I do not find this image quite as helpful as was the case with the five-part compounds described above.

Which of these images do you find most illuminating? As always, comments are welcome.

Four Different Clusters of Multiple Rhombicosidodecahedra

To make the cluster above, I began with the compound of five octahedra, which has 5(8) = 40 faces, all of them equilateral triangles. Next, I augmented each of those triangular faces with a single rhombicosidodecahedron — forty in all.

Next, I started anew with the compound of five dodecahedra, which has 5(12) = 60 pentagonal faces, all of them regular. Each of these sixty pentagons was then augmented by a single rhombicosidodecahedron.

For the next cluster, I started with the most well-known compound of ten tetrahedra. There are actually two such compounds; I used the one which is the compound of the chiral five-tetrahedron compound, combined with its mirror image. Since 10(4) = 40, this cluster, like the first one in this post, contains forty rhombicosidodecahedra. Unlike the other models shown here, this one has “holes,” which you can see as it rotates, but the reason for this is a mystery to me. The same is true for the first cluster shown in this post.

There also exist two compounds of eight tetrahedra each, and I used one of them for this next cluster, using the same procedure, so this cluster is composed of 8(4) = 32 rhombicosidodecahedra.

All four of these clusters were created with Stella 4d, a program you may try for free here.

Polyhedral Violets and a Blue Sky

Created with Stella 4d, available here.

The Final Stellation of the Great Rhombicosidodecahedron, Together with Its Dual

In the last post, several selections from the stellation-series of the great rhombicosidodecahedron (which some people call the truncated icosidodecahedron) were shown. It’s a long stellation-series — hundreds, or perhaps thousands, or even millions, of stellations long (I didn’t take the time to count them) — but it isn’t infinitely long. Eventually, if repeatedly stellating this polyhedron, one comes to what is called the “final stellation,” which looks like this:

Stellation-series “wrap around,” so if this is stellated one more time, the result is the (unstellated) great rhombicosidodecahedron. In other words, the series starts over.

The dual of the great rhombicosidodecahedron is called the disdyakis triacontahedron. The reciprocal function of stellation is faceting, so the dual of the figure above is a faceted disdyakis triacontahedron. Here is this dual:

To complicate matters further, there is more than one set of rules for stellation. For an explanation of this, I refer you to this Wikipedia page. In this post, and the one before, I am using what are known as the “fully supported” rules.

Both these images were made using Stella 4d, software you can buy, or try for free, right here. When stellating polyhedra using this program, it can be set to use different rules for stellation. I usually leave it set for the fully supported stellation criteria, but other polyhedron enthusiasts have other preferences.

Two Compounds with Pyritohedral Symmetry: the Icosidodecahedron / Truncated Octahedron Compound, and the Rhombic Triacontahedron / Tetrakis Cube Compound

Stella 4d, a program you can try here, was used to create these two compounds. Both have pyritohedral symmetry: the symmetry of a standard volleyball. The two compounds are also duals.