If you live in the USA, you are probably familiar with the phrase “free lunch,” or “free and reduced lunch,” as used in a public-school context. For those outside the USA, though, an explanation of what that phrase means, in practice, may be helpful, before I explain why a different name for such lunches should be used.

The term “free and reduced lunch” originated with a federal program which pays for school lunches, as well as breakfasts, with money collected from taxpayers — for students whose families might otherwise be unable afford these meals. The program’s eligibility requirements take into account both family income and size. There’s a problem with it, though: the inaccuracy of the wording used, especially the troublesome word “free.” The acronym above, “TANSTAAFL,” is familiar to millions, from the works of Robert A. Heinlein (science fiction author), Milton Friedman (Nobel-Prize-winning economist), and others. It stands for the informally-worded phrase, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch,” which gets to the heart of the problem with the terminology we use when discussing school lunches. (Incidentally, I have seen an economics textbook use the phrase “TINSTAAFL,” in its place, to change “ain’t no” to “is no.” I do not use this version, though, for I am unwilling to correct the grammar of a Nobel laureate.)

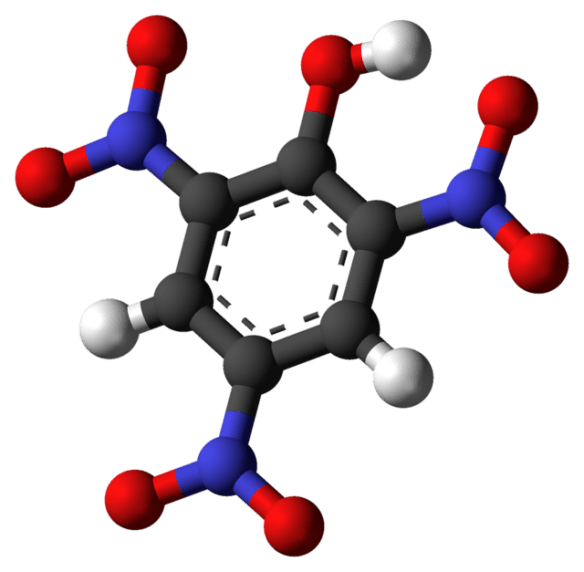

The principle that “free lunches” simply do not exist is an important concept in both physics and economics, as well as other fields. In physics, we usually call it the Law of Conservation of Mass and Energy, or the First Law of Thermodynamics. This physical law has numerous applications, and has been key to many important discoveries. Learning to understand it, deeply, is an essential step in the education of anyone learning physics. Those who teach the subject, as I have in many past years, have an even more difficult task: helping students reach the point where they can independently apply the TANSTAAFL principle to numerous different situations, in order to solve problems, and conduct investigations in the laboratory. It is a fundamental statement of how the universe works: one cannot get something for nothing.

TANSTAAFL applies equally well in economics, where it is related to such things as the fact that everything has a cost, and those costs, while they can be shifted, cannot be made to simply disappear. It is also related to the principle that intervention by governments in the economy always carries costs. For example, Congress could, hypothetically, raise the federal minimum wage to $10 per hour — but the cost of doing so would be increased unemployment, especially for those who now have low-paying jobs. Another possible cost of a minimum-wake hike this large would be a sudden spike in the rate of inflation, which would be harmful to almost everyone.

To understand what people have discovered about the fundamental nature of physical reality, physics must be studied. To understand what is known about social reality in the modern world, economics must be studied. Both subjects are important, and understanding the TANSTAAFL principle is vital in both fields. Unfortunately, gaining that understanding has been made more difficult, for those educated in the United States, simply because of repeated and early exposure to the term “free lunch,” from childhood through high school graduation. How can we effectively teach high school and college students that there are no free lunches, when they have already been told, incessantly, for many years, that such things do exist? The answer is that, in many cases, we actually can’t — until we have first helped our students unlearn this previously-learned falsehood, for it stands in the way of the understanding they need. It isn’t a sound educational practice to do anything which makes it necessary for our students to unlearn untrue statements.

I am not advocating abolition, nor even reduction, of this federal program, which provides essential assistance for many families who need the help. Because I am an American taxpayer, in fact, I directly participate in funding this program, and do not object to doing so. I do take issue, however, with this program teaching students, especially young, impressionable children in elementary school, something which is untrue.

We need to correct this, and the solution is simple: call these school lunches what they actually are. They aren’t free, for we, the taxpayers, pay for them. Nothing is free. We should immediately replace the phrase “free and reduced lunch” with the phrase “taxpayer-subsidized lunch.” The second phrase is accurate. It tells the truth, but the first phrase does the opposite. No valid reason exists to try to hide this truth.