Those who have taught geometry, when teaching triangle congruence, go through a familiar pattern. SSS (side-side-side) triangle congruence is usually taught first, as a postulate, or axiom — a statement so obvious that it requires no proof (although demonstrations certainly do help students understand such statements, even if rigorous proof is not possible). Next, SAS (side-angle-side) and ASA (angle-side-angle) congruence are taught, and most textbooks also present them as postulates. AAS (angle-angle-side) congruence is different, however, for it need not be presented without proof, for it follows logically from ASA congruence, paired with the Triangle Sum Theorem. With such a proof, of course, AAS can be called a theorem — and one of the goals of geometricians is to keep the number of postulates as low as possible, for we dislike asking people to simply accept something, without proof.

At about this point in a geometry course, because the subject usually is taught to teenagers, some student, to an audience of giggling and/or snickering, will usually ask something like, “When are we going to learn about angle-side-side?”

The simple answer, of course, is that there’s no such thing, but there’s a much better reason for this than simple avoidance of an acronym which many teenagers, being teenagers, find amusing. When I’ve been asked this question (and, yes, it has come up, every time I have taught geometry), I accept it as a valid question — since, after all, it is — and then proceed to answer it. The first step is to announce that, for the sake of decorum, we’ll call it SSA (side-side-angle), rather than using a synonym for a donkey (in all caps, no less), by spelling the acronym in the other direction. Having set aside the silliness, we can then tackle the actual, valid question: why does SSA not work?

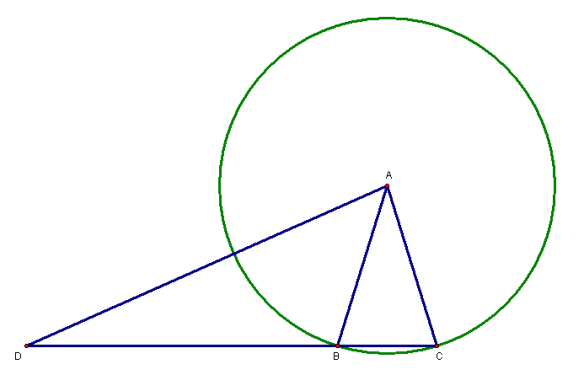

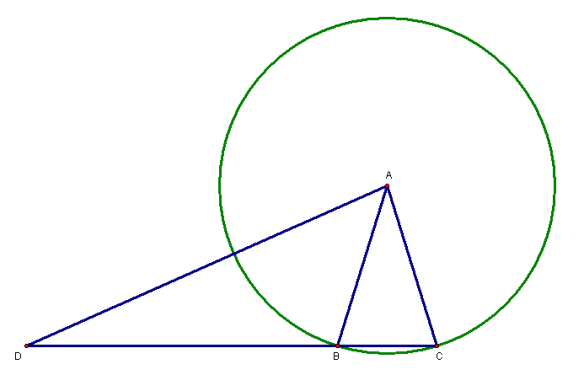

This actually is a question worth spending class time on, for it goes to the heart of what conjectures, theorems, proof, and disproof by counterexample actually mean. When I deal with SSA in class, I refer to it, first, as a conjecture: that two triangles can be shown to be congruent if they each contain two pairs of corresponding, congruent sides, and a pair of corresponding and congruent angles which are not included between the congruent sides, of either triangle. To turn a conjecture into a theorem requires rigorous proof, but, if a conjecture is false, only one counterexample is needed to disprove its validity. Having explained that, I provide this counterexample, to show why SSA does not work:

In this figure, A is at the center of the green circle. Since segments AB and AC are radii of the same circle, those two segments must be congruent to each other. Also, since congruence of segments is reflexive, segment AD must be congruent to itself — and, finally, because angle congruence is also reflexive, angle D must also be congruent to itself.

That’s two pairs of corresponding and congruent segments, plus a non-included pair of congruent and corresponding angles, in triangle ABD, as well as triangle ACD. If SSA congruence worked, therefore, we could use it to prove that triangle ABD and triangle ACD are congruent, when, clearly, they are not. Triangle ACD contains all the points inside triangle ABD, plus others found in isosceles triangle ABC, so triangles ABD and ACD are thereby shown to have different sizes — and, by this point, it has already been explained that two triangles are congruent if, and only if, they have the same size and shape. This single counterexample proves that SSA does not work.

Now, can this figure be modified, to produce an argument for a different type of triangle congruence? Yes, it can. All that is needed is to add the altitude to the base of isosceles triangle ABC, and name the foot of that altitude point E, thereby creating right triangle AED.

It turns out that, for right triangles only, SSA actually does work! The relevant parts of the right triangle, shown in red, are segment DA (congruent to itself, in any figure set up this way), segment AE (also congruent to itself), and the right angle AED (since all right angles are congruent to each other). However, as I’ve explained to students many times, we don’t call this SSA congruence, since SSA only works for right triangles. To call this form of triangle congruence SSA (forwards or backwards), when it only works for some triangles, would be confusing. We use, instead, terms that are specific to right triangles — and that’s how I introduce HL (hypotenuse-leg) congruence, which is what SSA congruence for right triangles is called, in order to avoid confusion. Only right triangles, of course, contain a hypotenuse.

This is simply one example of how to use a potentially-disruptive student question — also known as a teenager being silly — and turn it around, using it as an opportunity to teach something. Many other examples exist, of course, in multiple fields of learning.