I’ve been trying to figure out for over a year how to make images like the one above, without having holes in the two polyhedra, facing each other. At last, that puzzle of polyhedral manipulation using Stella 4d (software available at this website) has been solved: use augmentation followed by faceting, rather than augmentation followed by simply hiding faces.

Monthly Archives: June 2015

Two Similar Polyhedra with Icosidodecahedral Symmetry

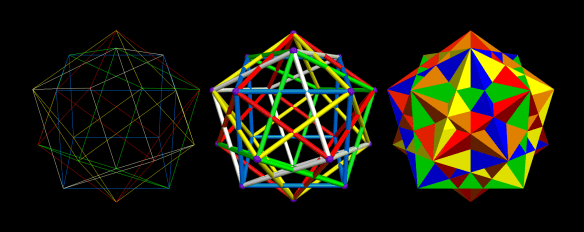

Three Different Depictions of the Compound of Five Cubes

The most common depiction of the compound of five cubes uses solid cubes, each of a different color:

This isn’t the only way to display this compound, though. If the faces of the cubes are hidden, then the interior structure of the compound can be seen. An edges-only depiction, still keeping a separate color for each cube, looks like this:

If these thin edges are then thickened into cylinders, that makes a third way to depict this polyhedral compound. It creates a minor problem, though: edges-as-cylinders looks awful without vertices shown as well, and the best way I have found to depict vertices, in this situation, is with spheres. With vertices shown as spheres, however, a sixth color, only for the vertex-spheres, is needed. Why? Because each vertex is shared by six edges: three from a cube of one color, and three from a second cube, of a different color.

Finally, here are all three versions, side-by-side for comparison, and with the motion stopped.

All images in this post were created using Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software you may try for free at this website.

My New Middle Initial and Name: A Mathematical Welcome-Back Gift from My Alma Mater

I just had a middle initial assigned to me, and then later, with help, figured out what that initial stood for. With apologies for the length of this rambling story, here’s an explanation for how such crazy things happened.

I graduated from high school in 1985, and then graduated college, for the first time, with a B.A. (in history, of all things), in 1992. My alma mater is the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, or UALR, whose website at http://www.ualr.edu is the source for the logo at the center of the image above.

Later, I transferred to another university, became certified to teach several subjects other than history, got my first master’s degree from there (also in history) in 1996, and then quit seeking degrees, but still added certification areas and collected salary-boosting graduate hours, until 2005. In 2005, the last time I took a college class (also at UALR), I suddenly realized, in horror, that I’d been going to college, off and on, for twenty years. That, I immediately decided, was enough, and so I stopped — and stayed stopped, for the past ten years.

Now it’s 2015, and I’ve changed my mind about attending college — again. I’ve been admitted to a new graduate program, back at UALR, to seek a second master’s degree — one in a major (gifted and talented education) more appropriate for my career, teaching (primarily) mathematics, and the “hard” sciences, for the past twenty years. After a ten-year break from taking classes, I’ll be enrolled again in August.

As part of the process to get ready for this, UALR assigned an e-mail address to me, which they do, automatically, using an algorithm which uses a person’s first and middle initial, as well as the person’s legal last name. With me, this posed a problem, because I don’t have a middle name.

UALR has a solution for this: they assigned a middle initial to me, as part of my new e-mail address: “X.” Since I was not consulted about this, I didn’t have a clue what the “X” even stands for, and mentioned this fact on Facebook, where several of my friends suggested various new middle names I could use.

With thanks, also, to my friend John, who suggested it, I’m going with “Variable” for my new middle name — the name which is represented by the “X” in my new, full name.

I’ve even made this new middle initial part of my name, as displayed on Facebook. If that, plus the e-mail address I now have at UALR, plus this blog-post, don’t make this official, well, what possibly could?

Various Views of Three Different Polyhedral Compounds: Those of (1) Five Cuboctahedra, (2) Five of Its Dual, the Rhombic Dodecahedron, and (3) Ten Components — Five Each, of Both Polyhedra.

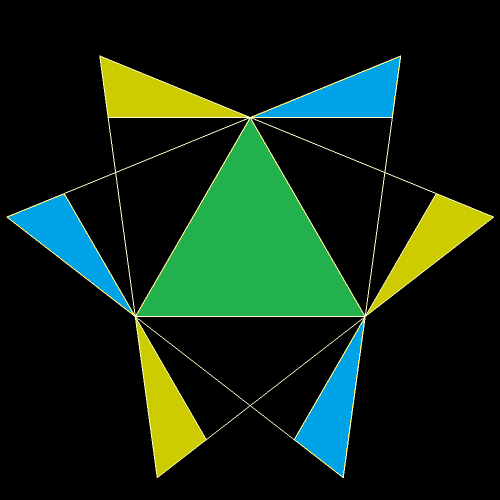

Polyhedral compounds differ in the amount of effort needed to understand their internal structure, as well as the way the compounds’ components are assembled, relative to each other. This compound, the compound of five cuboctahedra, and those related to it, offer challenges not offered by all polyhedral compounds, especially those which are well-known.

The image above (made with Stella 4d, as are others in this post — software available here) is colored in the traditional style for compounds: each of the five cuboctahedra is assigned a color of its own. There’s a problem with this, however, and it is related to the triangular faces, due to the fact that these faces appear in coplanar pairs, each from a different component of the compound.

The yellow regions above are from a triangular face of the yellow component, while the blue regions are from a blue triangular face. The equilateral triangle in the center, being part of both the yellow and blue components, must be assigned a “compromise color” — in this case, green. The necessity of such compromise-colors can make understanding the compound by examination of an image more difficult than it with with, say, the compound of five cubes (not shown, but you can see it here, if you wish). Therefore, I decided to look at this another way: coloring each face of the five-cuboctahedra compound by face type, instead of by component.

Another helpful view may be created by simply hiding all the faces, revealing internal structure which was previously obscured.

Since the dual of the cuboctahedron is the rhombic dodecahedron, the dual of the compound above is the compound of five rhombic dodecahedra, shown, first, colored by giving each component a different color.

A problem with this view is that most of what’s “going on” (in the way the compound is assembled) cannot be seen — it’s hidden inside the figure. An option which helped above (with the five-cuboctahedra compound), coloring by face type, is not nearly as helpful here:

Why wasn’t it helpful? Simple: all sixty faces are of the same type. It can be made more attractive by putting Stella 4d into “rainbow color” mode, but I cannot claim that helps with comprehension of the compound.

With this compound, what’s really needed is a “ball-and-stick” model, with the faces hidden to reveal the compound’s inner structure.

Since the two five-part compounds above are duals, they can also be combined to form a ten-part compound: that of five cuboctahedra and five rhombic dodecahedra. In the first image below, each of the ten components is assigned its own color.

In this ten-part compound, the coloring-problem caused in the first image in this post, coplanar and overlapping triangles of different colors, vanishes, for those regions of overlap are hidden in the ten-part compound’s interior. This is one reason why this coloring-scheme is the one I find the most helpful, for this ten-part compound (unlike the two five-part compounds above). However, so that readers may make this choice for themselves, two other versions are shown below, starting with coloring by face type.

Finally, the hollow version of this ten-part compound. This is only a personal opinion, but I do not find this image quite as helpful as was the case with the five-part compounds described above.

Which of these images do you find most illuminating? As always, comments are welcome.

99% of Critical

Created using Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software which is available for either purchase, or a free trial download, right here.

Flying Kites into the Snub Dodecahedron, a Dozen at a Time, Using Tetrahedral Stellation

I’ve been shown, by the program’s creator, a function of Stella 4d which was previously unknown to me, and I’ve been having fun playing around with it. It works like this: you start with a polyhedron with, say, icosidodecahedral symmetry, set the program to view it as a figure with only tetrahedral symmetry (that’s the part which is new to me), and then stellate the polyhedron repeatedly. (Note: you can try a free trial download of this program here.) Several recent posts here have featured polyhedra created using this method. For this one, I started with the snub dodecahedron, one of two Archimedean solids which is chiral.

Using typical stellation (as opposed to this new variety), stellating the snub dodecahedron once turns all of the yellow triangles in the figure above into kites, covering each of the red triangles in the process. With “tetrahedral stellation,” though, this can be done in stages, producing a greater variety of snub-dodecahedron variants which feature kites. As it turns out, the kites appear twelve at a time, in four sets of three, with positions corresponding to the vertices (or the faces) of a tetrahedron. Here’s the first one, featuring one dozen kites.

Having done this once (and also changing the colors, just for fun), I did it again, resulting in a snub-dodecahedron-variant featuring two dozen kites. At this level, the positions of the kite-triads correspond to those of the vertices of a cube.

You probably know what’s coming next: adding another dozen kites, for a total of 36, in twelve sets of three kites each. At this point, it is the remaining, non-stellated four-triangle panels, not the kite triads, which have positions corresponding to those of the vertices of a cube (or the faces of an octahedron, if you prefer).

Incoming next: another dozen kites, for a total of 48 kites, or 16 kite-triads. The four remaining non-stellated panels of four triangles each are now arranged tetrahedrally, just as the kite-triads were, when the first dozen kites were added.

With one more iteration of this process, no triangles remain, for all have been replaced by kites — sixty (five dozen) in all. This is also the first “normal” stellation of the snub dodecahedron, as mentioned near the beginning of this post.

From beginning to end, these polyhedra never lost their chirality, nor had it reversed.

A Compound of the Octahedron, and a Pyritohedral Dodecahedron

This compound is the first I have seen which combines a Platonic solid (the blue octahedron) with a pyritohedral modification of a Platonic solid. Here’s what a pyritohedral dodecahedron looks like, by itself:

Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator was used to make these — software you can try right here: http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php.

A (Possible) New Near-Miss to the Johnson Solids

In the polyhedron above, the octagons, hexagons, and triangles are regular. The only irregularities are found in the near-squares, which are actually isosceles trapezoids with three edges of equal length: the ones shared with the octagons and hexagons. The trapezoid-edges adjacent to the triangles, however, are ~15.89% longer than its other three edges. As a result, two of the interior angles of the trapezoids measure ~85.44º (the ones nearest the triangles), while the other two (adjacent to the shorter of the two trapezoid bases) measure ~94.56º. In a rotating model, it can be difficult to see the irregularities in these trapezoids. Were someone to build an actual physical model, however, the fact that they are not squares would be far more obvious.

In case someone would like to build such a model, here is a net you can use.

As you can see on this Wikipedia page, near-misses are not precisely defined — nor can they be, without such a definition (including something such as “no edge may be more than 10% longer than any other) being unjustifiably arbitrary. Instead, new near-miss candidates are discussed among members of the small community of polyhedral enthusiasts with an interest in near-misses, and are either admitted to the set of recognized near-misses, or not, based on consensus of opinion. This isn’t an entirely satisfactory system, but it’s the best we have, and may even be the best system possible.

The shortest definition for “near-miss Johnson solid” is simply “a polyhedron which is almost a Johnson solid.” Recently, a new (and even more informal) term has been created: the “near near-miss,” for polyhedra which are almost near-misses, but with deviations from regularity which are too large, by consensus of opinion, to be called near-misses. This polyhedron may well end up labeled a “near near-miss,” rather than a genuine near-miss.

Several questions remain at this point, and once I have found the answers, I will update this post to include them.

- Is this close enough to being a Johnson solid to be called a near-miss, or merely a “near near-miss?”

- Has this polyhedron already been found before? It looks quite familiar to me, and so it is entirely possible I have seen it before, and have simply forgotten when and where I saw it. On the other hand, this “I’ve seen it before” feeling may be caused by this polyhedron’s similarity to the great rhombcuboctahedron (also known as the truncated cuboctahedron, and a few other names), one of the Archimedean solids.

- Does this polyhedron already have a name?

- If unnamed at this time, what name would be suitable for it?

All the images in this post were created using Stella 4d, and I also used this software to obtain the numerical data given above. A free trial download of this program is available, and you can find it at http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php. Also, since it was mentioned above, I’ll close this post with a rotating image of the great rhombcuboctahedron. Perhaps a suitable name for the near-miss candidate above would be the “expanded great rhombcuboctahedron,” although it is entirely possible that a better name will be found.

Update #1: I now remember where I’ve seen this before: right here on my own blog! You can find that post here. I could delete this, as a duplicate post, but am choosing not to. One reason: the paths I took to create these two identical polyhedra were entirely different. Another reason is that this post includes information not included the first time around.

Update #2: This was already discussed among my circle of polyhedral enthusiasts. As I now recall, the irregularity in the quadrilaterals was agreed to be too large to call this a true “near-miss,” so, clearly, it’s a “near near-miss” instead.

Five More Clusters of Rhombicosidodecahedra

Making the four different clusters of rhombicosidodecahedra seen in the post right before this one was fun, so I decided to make more of them.

There are two different forms of the compound of twenty tetrahedra. To make the polyhedral cluster above, I chose one of them, and then augmented each of its 20(4) = 80 triangular faces with a rhombicosidodecahedron.

For the next of these clusters, I decided to move away from using compounds for the central, hidden figure. Instead, I chose a snub cube, and augmented each of its 32 triangular faces with a rhombicosidodecahedron. Since the snub cube is chiral, this cluster is chiral as well.

Any chiral polyhedron can be combined with its mirror-image to produce a new compound, and that’s what I did to make this next cluster, which is composed of 64 rhombicosidodecahedra: I simply added the cluster above to its own reflection.

Next, I turned to the snub dodecahedron, also chiral, and with 80 triangular faces. Augmentation of all 80 produced this chiral cluster of 80 rhombicosidodecahedra:

Finally, I added this last cluster to its own mirror-image, producing this symmetrical cluster of 160 rhombicosidodecahedra.

Each of these was created using a program called Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, software you can try for free right here.