The troy ounce is a unit of mass, not weight, and is used exclusively for four precious metals. At this time, the prices per troy ounce, according to this source for current precious metal prices, for these four elements, are:

- Gold, $1,094

- Palladium, $600

- Platinum, $965

- Silver, $14.82

(As a side note, it is rare for platinum to have a lower price per troy ounce than gold, as is now the case. I would explain the reasons this is happening, except for one problem: I don’t understand the reasons, myself, well enough to do so. Yet.)

A troy ounce equals 31.1034768 grams, but, for most purposes, 31.103 g, or even 31.1 g, works just fine.

Also, as you can see here, these “troy elements” are all in one part of the periodic table. This is related to the numerous similarities in these elements’ physical and chemical properties, which is itself related, of course, to the suitability of these four elements for such things as jewelry, coinage, and bullion.

To determine the volume of a given mass of one of these metals, it is also necessary to know their densities, so I looked them up, using Google (they are not listed on the periodic table above):

- Gold, 19.3 g/cm³

- Palladium, 11.9 g/cm³

- Platinum, 21.46 g/cm³

- Silver, 10.49 g/cm³

In chemistry, of course, one must often deal with elements (as well as other chemicals) in terms of the numbers of units (such as atoms or molecules), except for one problem: this is absurdly impractical, due to the outrageously small size of atoms. Despite this, though, it is necessary to count such things as atoms in order to do much chemistry at all, so chemists have devised a “workaround” for this problem: when counting units of pure chemicals, they don’t count such things as atoms or molecules directly, but count them a mole at a time. A mole is defined as a number of things equal to the number of atoms in exactly 12 grams of pure carbon-12. To three significant figures, this number is 6.02 x 10²³. To deal with moles, since atoms have differing masses, we need to know the molar mass (mass of one mole) of whatever we are dealing with to convert, both directions, between moles and grams. Here are the molar masses of the four troy-measured elements, as seen on the periodic table above, below each element’s symbol.

- Gold, 196.97 g

- Palladium, 106.42 g

- Platinum, 195.08 g

- Silver, 107.87 g

I’ve given these numbers as the information needed to solve the following problem: rank one dozen precious metal cubes (descriptions follow) by ascending order of volume. There are three cubes each of gold, palladium, platinum, and silver. Four of the twelve (one of each element) have a mass of one troy ounce each. Another four each have a value, at the time of this writing, of $1,000. The last set of four each contain one mole of the element which composes the cube, and, again, there is one of each of these same four elements in the set.

If you would like to do this problem for yourself, the time to stop reading is now. Otherwise (or to check your answers against mine), just scroll down.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In the solutions which follow, a rearrangement of the formula for density (d=m/v) is used; solved for v, this equation becomes v = m/d. In order, then, by both volume and edge length, from smallest to largest, here are the twelve cubes:

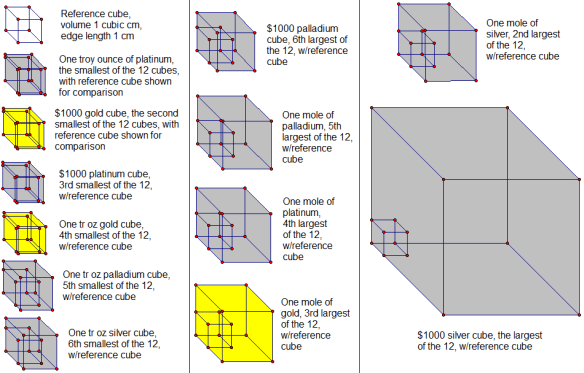

Smallest cube: one troy ounce of platinum

One tr oz, or 31.103 g, of platinum would have a volume of v = m/d = 31.103 g / (21.46 g/cm³) = 1.449 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length equal to the its volume’s cube root, or 1.132 cm. (This explanation for the calculation of the edge length, given the cube’s volume, is omitted in the items below, since the mathematical procedure is the same each time.)

Second-smallest cube: $1000 worth of gold

Gold worth $1000, at the time of this posting, would have a troy mass, and then a mass in grams, of $1000.00/($1,094.00/tr oz) = (0.914077 tr oz)(31.103 g/tr oz) = 28.431 g. This mass of gold would have a volume of v = m/d = 28.431 g / (19.3 g/cm³) = 1.47 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.14 cm.

Third-smallest cube: $1000 worth of platinum

Platinum worth $1000, at the time of this posting, would have a troy mass, and then a mass in grams, of $1000.00/($965.00/tr oz) = (1.0363 tr oz)(31.103 g/tr oz) = 32.231 g. This mass of platinum would have a volume of v = m/d = 32.231 g / (21.46 g/cm³) = 1.502 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.145 cm.

Fourth-smallest cube: one troy ounce of gold

One tr oz, or 31.1 g, of gold would have a volume of v = m/d = 31.1 g / (19.3 g/cm³) = 1.61 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.17 cm.

Fifth-smallest cube: one troy ounce of palladium

One tr oz, or 31.1 g, of palladium would have a volume of v = m/d = 31.1 g / (11.9 g/cm³) = 2.61 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.38 cm.

Sixth-smallest cube: one troy ounce of silver

One tr oz, or 31.103 g, of silver would have a volume of v = m/d = 31.103 g / (10.49 g/cm³) = 2.965 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.437 cm.

Sixth-largest cube: $1000 worth of palladium

Palladium worth $1000, at the time of this posting, would have a troy mass, and then a mass in grams, of $1000.00/($600.00/tr oz) = (1.6667 tr oz)(31.103 g/tr oz) = 51.838 g. This mass of palladium would have a volume of v = m/d = 51.838 g / (11.9 g/cm³) = 4.36 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 1.63 cm.

Fifth-largest cube: one mole of palladium

A mole of palladium, or 106.42 g of it, would have a volume of v = m/d = 106.42 g / (11.9 g/cm³) = 8.94 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 2.07 cm.

Fourth-largest cube: one mole of platinum

A mole of platinum, or 195.08 g of it, would have a volume of v = m/d = 195.08 g / (21.46 g/cm³) = 9.090 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 2.087 cm.

Third-largest cube: one mole of gold

A mole of gold, or 196.97 g of it, would have a volume of v = m/d = 196.97 g / (19.3 g/cm³) = 10.2 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 2.17 cm.

Second-largest cube: one mole of silver

A mole of silver, or 107.87 g of it, would have a volume of v = m/d = 107.87 g / (10.49 g/cm³) = 10.28 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 2.175 cm.

Largest cube: $1000 worth of silver

Silver worth $1000, at the time of this posting, would have a troy mass, and then a mass in grams, of $1000.00/($14.82/tr oz) = (67.48 tr oz)(31.103 g/tr oz) = 2099 g. This mass of gold would have a volume of v = m/d = 2099 g / (10.49 g/cm³) = 200.1 cm³. A cube with this volume would have an edge length of 5.849 cm.

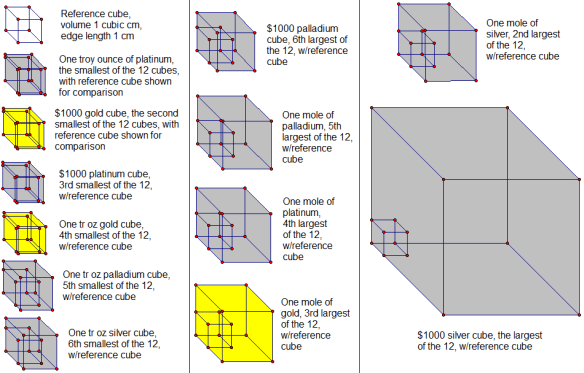

Finally, here are pictures of all 12 cubes, with 1 cm³ reference cubes for comparison, all shown to scale, relative to one another.

A third of these cubes change size from day-to-day, and sometimes even moment-to-moment during the trading day, if their value is held constant at $1000 — which reveals, of course, which four cubes they are. The other eight cubes, by contrast, do not change size — no precious metal prices were used in the calculation of those cubes’ volumes and edge lengths, precisely because the size of those cubes is independent of such prices, due to the way those cubes were defined in the wording of the original problem.