To build an octahedral lattice of rhombic triacontahedra, start with a single rhombic triacontahedron.

Next, augment its faces with more rhombic triacontahedra — but not all thirty faces. Instead, only augment six of them — the six which lie along mutually-perpendicular x-, y-, and z-axes. Another way to look at this is that you only augment the North, South, East, West, top, and bottom faces.

There are now seven rhombic triacontahedra in this small lattice, and one can begin to see the octahedral structure which is forming. The next step is to perform the same type of augmentation on each of the rhombic triacontahedra which exist at this point.

The overall octahedral shape of this lattice is now quite obvious. Also, there is one rhombic triacontahedron in the center, six in the layer next to the center, and eighteen in the outer layer, for a total of 1 + 6 + 18 = 25 rhombic triacontahedra, in the third of these figures, immediately above.

This latest augmentation increases the number of rhombic triacontahedra in the cluster by 38, for a total of 25 + 38 = 63 rhombic triacontahedra in the lattice shown immediately above. This pattern can, of course, be continued indefinitely — and, as it increases, the overall octahedral shape of the lattice becomes progressively more clear.

At this point, the 5th in the sequence, the number of new triacontahedra added, in the outermost layer, becomes more difficult to count, but it is certainly possible. In the middle level of this outermost layer, there are sixteen new triacontahedra. In the levels above and below that, there are twelve new rhombic triacontahedra, each. The next levels up and down contain eight more, each. Above and below those two levels, there are four each — and going one more step up and down takes one to the top, with one rhombic triacontahedron at the top, plus one more at the bottom. The number of new rhombic triacontahedra is, therefore, 16 + 12 + 12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1, which equals 66. Add 66 more (on the outside) to the 63 already inside, and you have the total number of rhombic triacontahedra in this latest lattice: 129.

The number of rhombic triacontahedra at each point in this series of geometric shapes is, itself, interesting. Here’s what we have so far.

- When n = 1, there is 1, or n, rhombic triacontahedral “cell” in the structure.

- When n = 2, there are (1) + (4 + 1 + 1) = 1 + 6 = 7 cells. This is also equal to 3(1) + (4).

- When n = 3, there are (1) + (4 + 1 + 1) + (8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) = 1 + 6 + 18 = 25 cells. This also equals 5(1) + 3(4) + 1(8).

- At n = 4, this number increases to (1) + (4 + 1 + 1) + (8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) = 1 + 6 + 18 + 38 = 63. This also equals 7(1) + 5(4) + 3(8) + 1(12).

- At n = 5, this sum is now (1) + (4 + 1 + 1) + (8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (16 + 12 + 12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) = 1 + 6 + 18 + 38 + 66 = 129. This also equals 9(1) + 7(4) + 5(8) + 3(12) + 1(16), which can also be written as 9 + 28 + 40 + 36 + 16.

Here is the next octahedral lattice of rhombic triacontahedra, with n = 6.

Now, at n = 6, this sum of the number of cells is (1) + (4 + 1 + 1) + (8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (16 + 12 + 12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) + (20 + 16 + 16 + 12 + 12 + 8 + 8 + 4 + 4 + 1 + 1) = 1 + 6 + 18 + 38 + 66 + 102 = 129 interior cells + 102 exterior cells = 231 cells, total. This also equals 11(1) + 9(4) + 7(8) + 5(12) + 3(16) + 1(20), which can also be written as 11 + 36 + 56 + 60 + 48 + 20. In terms of n, when n = 6, 11 + 36 + 56 + 60 + 48 + 20 may also be written as (2n – 1)(1) + (2n – 3)[4(n – 5)] + (2n – 5)[4(n – 4)] + (2n – 7)[4(n – 3)] + (2n – 9)[4(n – 2)] + (2n – 11)[4(n – 1)].

Obviously, I am trying to find a way to express the number of cells in the nth figure, in terms of n, but with only limited success, so far. The first six terms are 1, 7, 25, 63, 129, 231, and patterns of numbers above could easily be used to predict the seventh term, but that’s not my goal. What I want is a simple formula which will give me the total number of cells, in terms of n, for the nth of these octahedral lattices of rhombic triacontahedra. I’ll go ahead and find the seventh term, though, in the hope that it will help me figure out the pattern. When n = 7, the total number of cells will equal 13(1) + 11(4) + 9(8) + 7(12) + 5(16) + 3(20) + 1(24) = 13 + 44 + 72 + 84 + 80 + 60 + 24 = 377. Having found that number, I might as well throw in another picture, also. Stella 4d: Polyhedron Navigator, makes these rotating images easy to make, and you can try that program’s trial version for free, or purchase the fully-functioning version I use, at http://www.software3d.com/Stella.php.

This did help: it helped me avoid a dead end (later edit: or so I thought). I had noticed that the first six terms (1, 7, 25, 63, 129, 231) stayed close to, or matched exactly, the cubes of the first six counting numbers (1, 8, 27, 64, 125, 216), with only the sixth term deviating far from the sixth perfect cube. With the seventh term, 377, the deviation from the seventh perfect cube, 343, grows even wider, so, at this point, I don’t think the solution is related to perfect cubes in any way. (However, please keep reading; sometimes things which appear to be mathematical dead ends are actually only illusions of dead ends.)

I’m not yet willing to give up, though. I will next analyze the differences in successive terms, the differences between those differences, and so on. For this, the eighth term might be helpful, so I’ll go ahead and find it. From one of the patterns above, I can see that the 8th term will equal 15(1) + 13(4) + 11(8) + 9(12) + 7(16) + 5(20) + 3(24) + 1(28) = 15 + 52 + 88 + 108 + 112 + 100 + 72 + 28 = 575. The cube of 8 is 512, so, as I expected, the deviation from the sequence of perfect cubes continues to widen. Here, also, is a picture for the next of these figures, when n = 8.

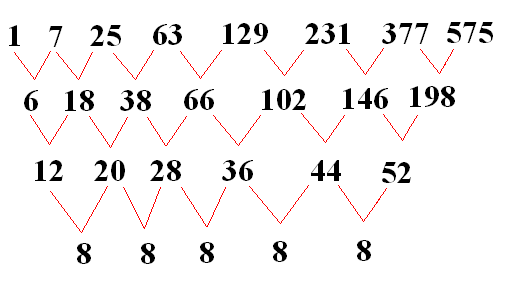

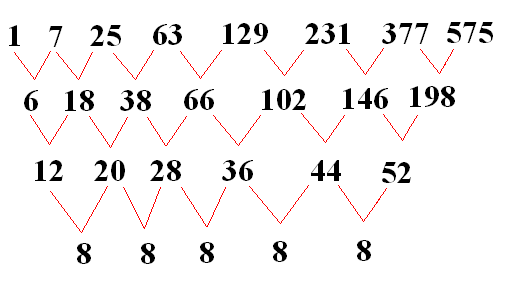

Now it is time for the analysis of differences in this sequence, the differences in those differences, and so on. Here goes….

Now this is helpful! It tells me that the solution to this problem will take the form a third-order polynomial, also known as a cubic equation — so my earlier idea that this sequence was not related to the perfect cubes was, I now know, completely false.

Now this is helpful! It tells me that the solution to this problem will take the form a third-order polynomial, also known as a cubic equation — so my earlier idea that this sequence was not related to the perfect cubes was, I now know, completely false.

I next struggled, for several hours, to find the cubic equation for the solution to this problem, without success. After finally giving up on finding the solution myself, I asked my wife to assist me (she’s also a math teacher, and her knowledge of algebra exceeds my own, for I specialize in geometry). She performed a cubic regression, and this is how we now know that the solution to this problem is that the number of cells for the nth figure in this sequence equals (4/3)n3 – 2n2 + (8/3)n – 1. I spent many hours on this problem, but my wife finished solving it in mere minutes!

It’s no wonder I couldn’t find this solution, for I was only considering integers as coefficients, since only whole numbers for answers make sense — which I thought, incorrectly, would require the coefficients to be integers. However, for every value of n I have tested, the number of thirds in the answer always ends up being a multiple of three, cancelling threes in all denominators, and yielding whole numbers for answers. In retrospect, this makes sense, considering that the octahedron is a dipyramid, and that there is a 1/3 in the pyramid’s volume formula.

I was originally seeking to make an informative and interesting blog-post when I started this. However, I didn’t anticipate that I would learn as much as I did from the experience. I’m giving my wife joint credit for this solution, for I would not have been able to solve this problem without her help.

[Later edit: more information about this sequence can be found on these two websites: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centered_octahedral_number and https://oeis.org/A001845. I did not know about these sites until after I had finished this post.]