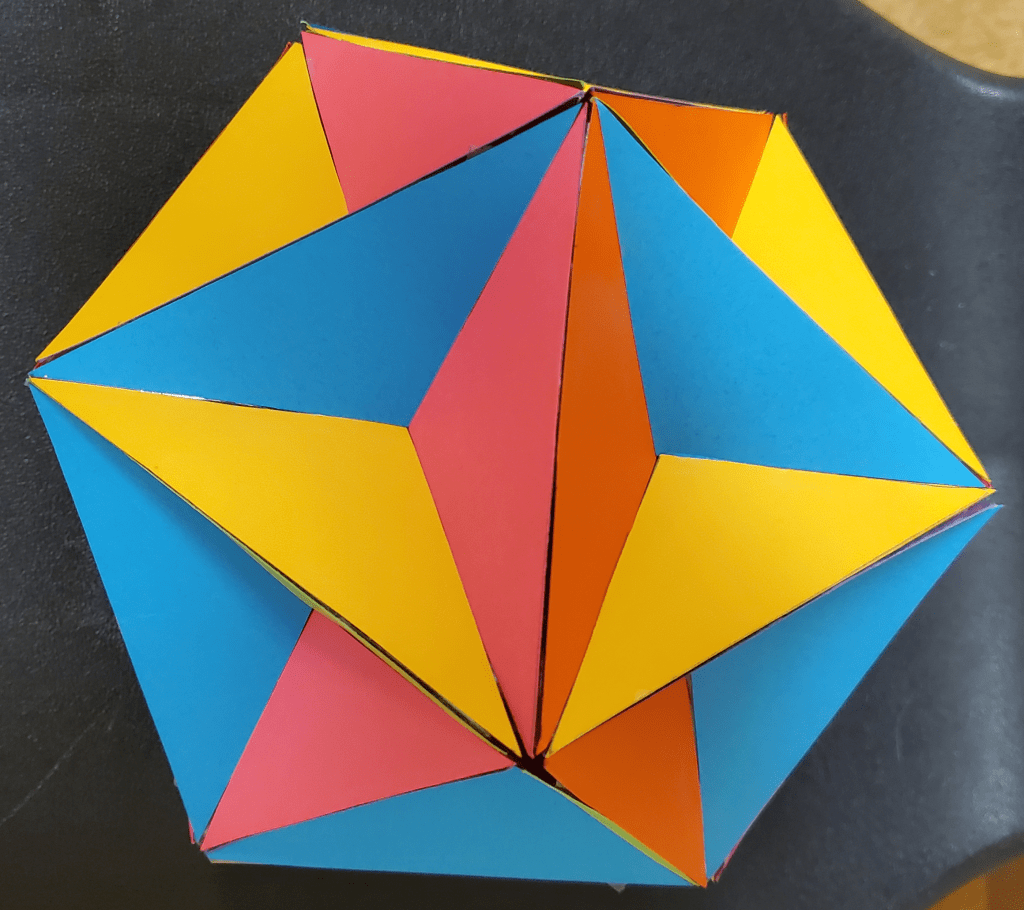

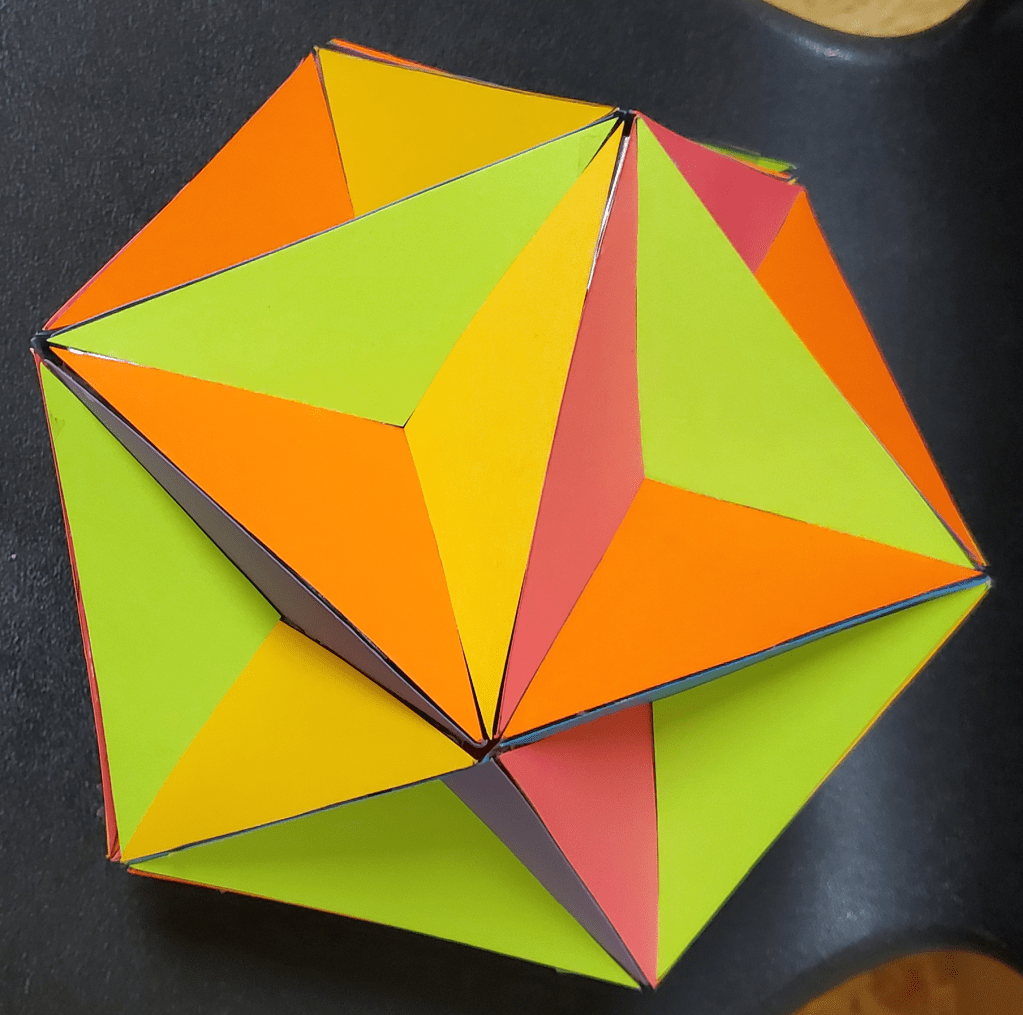

The obtuse triangles here are golden gnomons, which are isosceles triangles with vertex angles of 108 degrees, as well as base-to-leg ratios which are golden. These triangles are facelets; the actual, much larger faces are the regular pentagons of which the golden gnomons are parts. In this model, all facelets which are part of the same (or parallel) faces are all one color, with six colors of paper used, in all, for this non-convex, twelve-faced, regular polyhedron, which is one of the Kepler-Poinsot solids.

Much of each face is hidden from view in this polyhedron’s interior — or rather, this is the case for the mathematical construct called the great dodecahedron. This physical model, on the other hand, is hollow on the inside. One is made only of ideas, while the other is made of atoms.

No computer programs were involved in the construction of this model. It was made using compass, straight edge, scissors, card stock, pencils, and tape.