Tic-tac-toe, played by the traditional rules, is so simple a game that few people with two-digit ages ever play it — just because it’s boring. It is so simple a game, in fact, that chickens can be trained to play it, through extensive operant conditioning. Such chickens play the game at casinos, on occasion — with the rules stating that if the game ends in a tie, or the chicken wins, the human player loses the money they paid to play the game. If the human wins, however, they are promised a large reward — $10,000, for example. Don’t ever fall for such a trick, though, for casinos only use chickens that are so thoroughly trained, by weeks or months of positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and punishment, that they will not ever lose. You’d be better off simply saving the same money until it’s cold, and then setting it on fire, just for the heat. At least that way you’d be warm for a little while, and that certainly beats the humiliation of being beaten, at any game, by a literal bird-brain.

With a small, simple alteration, though, tic-tac-toe can actually become a worthwhile, interesting game, even for adults. I didn’t invent this variation, but have forgotten where I read about it. I call it “mutant tic-tac-toe.”

In this variation, each player can choose to play either “x” or “o” on each play — and the first person to get three “x”s or three “o”s, in a row, wins the game. That’s it — but, if you try it, you’ll find it’s a much more challenging game. I am confident chickens will never be trained to play it successfully.

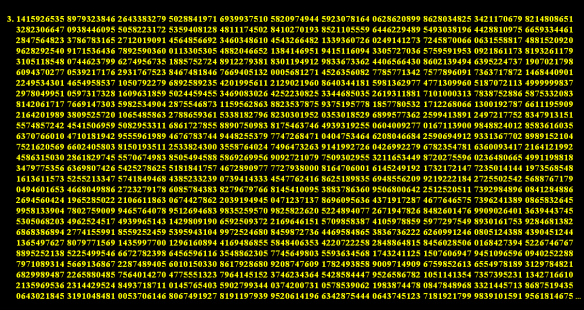

Consider the board pictured above, which happens to match a game I lost, to a high school student, earlier today. Red (the student) moved first, starting with the “o” in the center. I was playing with a blue marker, and chose to play an “x” in a corner spot. This was a mistake on my part, for the student’s next move — another “x,” opposite my “x,” effectively ended the game. I had to play next — passing is not allowed — and my playing an “x” or an “o,” in any of the six open spaces, would have led to an immediate victory by the student. If you study the board, you’ll see why this is the case.

Mutant tic-tac-toe is a great activity for semester exam week, at any school. Students who finish final exams earlier than their classmates can be taught the game quickly and quietly, and then they’ll entertain themselves with this game, rather than distracting students who are still working on their tests. What’s more, students have to really think to play this version of the game well, especially when they first learn it — and isn’t getting students to think what education is supposed to be all about, anyway?