Let me make it clear from the outset that this is a purely academic exercise. I don’t REALLY want to destroy any planet, let alone the one we live on, even though the beginning of this song — http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rR5xTgMwpiM — is my cell phone ringtone. I will admit that much.

But, seriously, how would one destroy a planet? I don’t mean kill everything on it — I mean utterly obliterate the whole ball of rock.

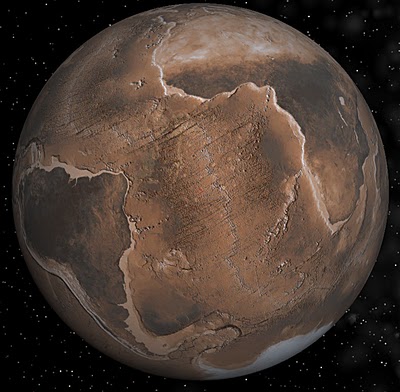

Well, let’s assume it isn’t a rogue planet, but one like ours. It orbits a star, in a nearly-circular orbit, and rotates on its axis. Let’s say it’s the blue one in this picture:

…and we want to know a way to destroy it — just as an interesting puzzle to solve. That’s all — I promise.

Well, planets that are closer to their stars orbit faster, which is why the planet Mercury is the fastest-moving planet in our solar system. Speed up the orbital velocity, then, and a planet’s orbit will get smaller in diameter, for faster planets orbit more quickly. In the diagram (not even close to being at scale for anything real), this is why the red planet’s velocity vector is shown as being longer (faster) than that of the blue planet.

So, speed up a planet enough, and its orbit will decay until it falls into its star, which should destroy it most effectively.

So it’s really pretty simple. On the blue planet, pile up a bunch of nuclear weapons, rocket engines — whatever you can find that invokes Newton’s Third Law of Motion — and start blasting at the position where you see the orange triangle (sundown, local time), right on the equator (unless there is axial tilt involved; correct for that if there is, and keep the blast site in the plane of the ecliptic). Keep blasting as the planet rotates for one-fourth of a rotation (counterclockwise), until the blast site is at midnight local time, and then stop. Repeat at the next sundown, and so on.

All of this blasting will speed up the blue planet’s orbital velocity. Eventually, it will end up where the red planet is, if you do this gradually enough to maintain near-circularity of the orbit (get too eccentrically elliptical, and other results may occur). Keep up this madness, and the target planet will end up slowly spiraling into its star.

That’s it. Game over.

Please do not try this at home, though. All my stuff is here.

[Later edit: I showed this to many of my science-geek friends, and they tore it to shreds. There are a lot of mistakes here. I considered taking it down, out of embarrassment, but have decided to leave it posted to remind myself that I can, and do, screw things up. I need such reminders!]