Unless you understand all of mathematics — and absolutely no one does — there is a point, for each of us, where mathematics no longer makes sense, at least at that moment. Subjectively, this can make the mathematics beyond this point, which always awaits exploration, appear to be some form of sorcery.

Mathematics isn’t supernatural, of course, but this is a reaction humans often have to that which they do not understand. Human reactions do not require logical purpose, and they don’t always make sense — but there is always a reason for them, even if that reason is sometimes simply that one is utterly bewildered.

In my case, this is the history of my own reactions, as I remember them, to various mathematical concepts. The order used is as close as I can remember to the sequence in which I encountered each idea. The list is, of necessity, incomplete.

- Counting numbers: no problem, but what do I call the next one after [last one I knew at that time]? And the next one? And the next? Next? Next? [Repeat, until everyone within earshot flees.]

- Zero exists: well, duh. That’s how much of whatever I’m snacking on is left, after I’ve eaten it all.

- Arithmetic: oh, I’m glad to have words for this stuff I’ve been doing, but couldn’t talk about before.

- Negative numbers: um, of course those must exist. No, I don’t want to hear them explained; I’ve got this already. What, you want me to demonstrate that I understand it? Ok, can I borrow a dollar? Oh, sure, I’ll return it at some point, but not until after I’ve spent it.

- Multiple digits, the decimal point, decimal places, place value: got it; let’s move on, please. (I’ve never been patient with efforts to get me to review things, once I understand them, on the grounds that review, under such conditions, is a useless activity.)

- Pi: love at first sight.

- Fractions: that bar means you divide, so it all follows from that. Got it. Say, with these wonderful things, why, exactly, do we need decimals, again? Oh, yeah, pi — ok, we keep using decimals in order to help us better-understand the number pi. That makes sense.

- “Improper” fractions: these are cool! I need never use “mixed numbers” again (or so I thought). Also, “improper” sounds much more fun than its logical opposite, and I never liked the term “mixed numbers,” nor the way those ugly things look.

- Algebra: ok, you turned that little box we used before into an “x” — got it. Why didn’t we just use an “x” to begin with? Oh, and you can do the same stuff to both sides of equations, and that’s our primary tool to solve these cool puzzles. Ok. Got it.

- Algebra I class: why am I here when I already know all this stuff?

- Inequality symbols: I’m glad they made the little end point at the smaller number, and the larger side face the larger number, since that will be pretty much impossible to forget.

- Scientific notation: well, I’m glad I get to skip writing all those zeroes now. If only I knew about this before learning number-names, up to, and beyond, a centillion. Oh well, knowing those names won’t hurt me.

- Exponents: um, I did this already, with scientific notation. Do not torture me with review of stuff I already know!

- Don’t divide by zero: why not? [Tries, with a calculator]: say, is this thing broken? [Tries dividing by smaller and smaller decimals, only slightly larger than zero]: ok, the value of the fraction “blows up” as the denominator approaches zero, so it can’t actually get all the way there. Got it.

- Nonzero numbers raised to the power of zero equal one: say what? [Sits, bewildered, until thinking of it in terms of writing the number one, using scientific notation: 1 x 10º.] Ok, got it now, but that was weird, not instantly understanding it.

- Sine and cosine functions: got it, and I’m glad to know what those buttons on the calculator do, now, but how does the calculator know the answers? It can’t possibly have answers memorized for every millionth of a degree.

- Tangent: what is this madness that happens at ninety degrees? Oh, right, triangles can’t have two right angles. Function “blows up.” Got it.

- Infinity: this is obviously linked to what happens when dividing by ever-smaller numbers, and taking the tangent of angles approaching a right angle. I don’t have to call it “blowing up” any more. Ok, cool.

- Factoring polynomials: I have no patience for this activity, and you can’t stop me from simply throwing the quadratic formula at every second-order equation I see.

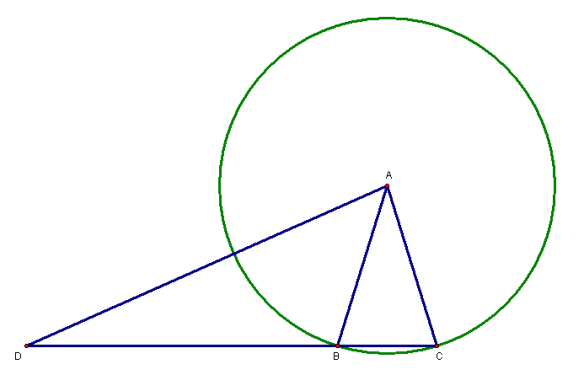

- Geometry (of the type studied in high school): speed this up, and stop stating the obvious all the time!

- Radicals: oh, I was wondering what an anti-exponent would look like.

- Imaginary numbers: well, it’s only fair that the negative numbers should also get square roots. Got it. However, Ms. _____________, I’d like to know what the square root of i is, and I’d like to know this as quickly as possible. (It took this teacher and myself two or three days to find the answer to this question, but find it we did, in the days before calculators would help with problems like this.)

- The phrase “mental math” . . . um, isn’t all math mental? Even if I’m using a calculator, my mind is telling my fingers which buttons to press on that gadget, so that’s still a mental activity. (I have not yielded from this position, and therefore do not use the now-despised “mental math” phrase, and, each time I have heard it, to date, my irritation with the term has increased.)

- 0.99999… (if repeated forever) is exactly equal to one: I finally understood this, but it took attacks from several different directions to get there, with headaches resulting. The key to my eventual understanding it was to use fractions: ninths, specifically.

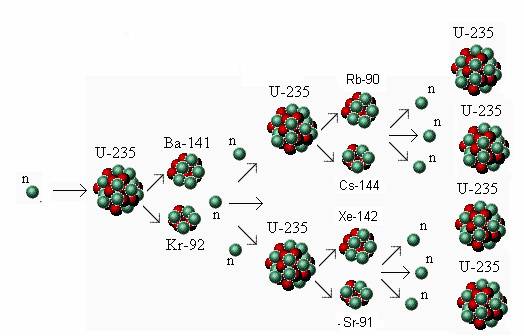

- The number e, raised to the power of iπ, equals -1: this is sorcery, as far as I can see. [Listens to, and attempts to read, explanations of this identity.] This still seems like sorcery!

- What it means to take the derivative of an expression: am I just supposed to memorize this procedure? Is no one going to explain to me why this works?

- Taking the derivative of a polynomial: ok, I can do this, but I don’t have the foggiest idea why I’m doing it, nor why these particular manipulations of one function give you a new function which is, at all points along the x-axis, the slope of the previous function. Memorizing a definition does not create comprehension.

- Integral calculus: this gives me headaches.

- Being handed a sheet of integration formulas, and told to memorize them: hey, this isn’t even slightly fun anymore. =(

- Studying polyhedra: I finally found the “sweet spot” where I can handle some, but not all, of the puzzles, and I even get to try to find solutions in ways different from those used by others, without being chastised. Yay! Math is fun again! =)

- Realizing, while starting to write this blog-post, that you can take the volume of a sphere, in terms of the radius, (4/3)πr³, take its derivative, and you get the surface area of the same sphere, 4πr²: what is this sorcery known as calculus, and how does it work, so it can stop looking like sorcery to me?

Until and unless I experience the demystification of calculus, this blog will continue to be utterly useless as a resource in that subfield of mathematics. (You’ve been warned.) The primary reason this is so unlikely is that I haven’t finished studying (read: playing with) polyhedra yet, using non-calculus tools I already have at my disposal. If I knew I would live to be 200 years old, or older, I’d make learning calculus right now a priority, for I’m sure my current tools’ usefulness will become inadequate in a century or so, and learning calculus now, at age 47, would likely be easier than learning it later. As things are, though, it’s on the other side of the wall between that which I understand, and that which I do not: the stuff that, at least for now, looks like magic — to me.

Please don’t misunderstand, though: I don’t “believe in” magic, but use it simply as a label of convenience. It’s a name for the “box ,” in my mind, where ideas are stored, but only if I don’t understand those ideas on first exposure. They remain there until I understand them, whether by figuring the ideas out myself, or hearing them explained, and successfully understanding the explanation, at which point the ideas are no longer thought of, on any level, as “magic.”

To empty this box, the first thing I would need would be an infinite amount of time. Once I accepted the inevitability of the heat death of the universe, I was then able to accept the fact that my “box of magic” would never be completely emptied, for I will not get an infinite amount of time.

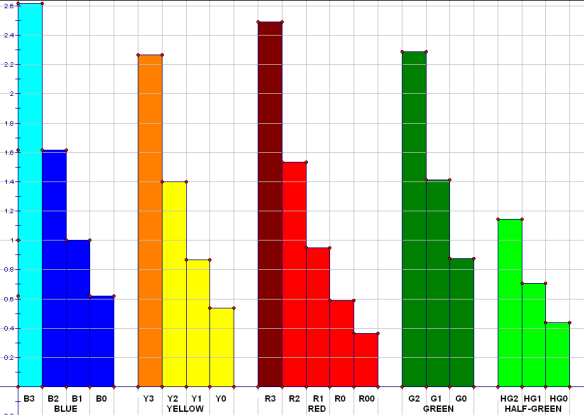

[Image credit: I made a rainbow-colored version of the compound of five cubes for the “magic box” picture at the top of this post, using Stella 4d, a program you may try here.]