Nineteen years ago, I began my teaching career at a small, private Arkansas high school. One of the classes I taught was Chemistry, and my principal happened to be a former chemistry teacher, himself. We were both new to the school, and knew that there was a high turnover rate there for teachers in that field. They’d had perhaps eight teachers for that class in the previous five years. I stayed there six years, teaching chemistry every year.

The new principal saw the need for upgraded laboratory facilities, and we got them, including a new, larger chemical stockroom. The old stockroom was a nightmare, and the chemicals needed to be transferred to their new home. This was a massive undertaking, for many of my predecessors had ordered chemicals, not taking the time to inventory the stockroom to see if the school already had what they needed. Even worse, the chemicals were stored in approximate alphabetical order.

Experienced chemists and chemistry teachers know how scary the phrase “alphabetical order” is, in this context. For reasons of safety, chemicals need to be stored by families, using a shelving pattern that keeps incompatible chemicals far apart. I was not an experienced teacher of anything at this point, but the principal showed me the classification scheme he’d used before, himself. It’s the one recommended by Flinn Scientific, and you can see it at http://www.flinnsci.com/store/Scripts/prodView.asp?idproduct=16069. At his direction, over a couple of weeks, I took the chemicals from the old storage area to the new one, de-alphabetizing them into a much safer arrangement, onto category-labelled shelves. In the process, of course, I saw every laboratory chemical that school had, recognizing many (jar after jar of liquid mercury, for example) as highly dangerous, and making certain proper precautions were taken with such substances. If I didn’t recognize a chemical well enough to categorize it (sulfates together, halides together, etc.), I looked it up, in order to find its place. I wouldn’t even open a container with an unfamiliar chemical in it, until researching it. As it turned out, my caution with unfamiliar chemicals literally saved my life.

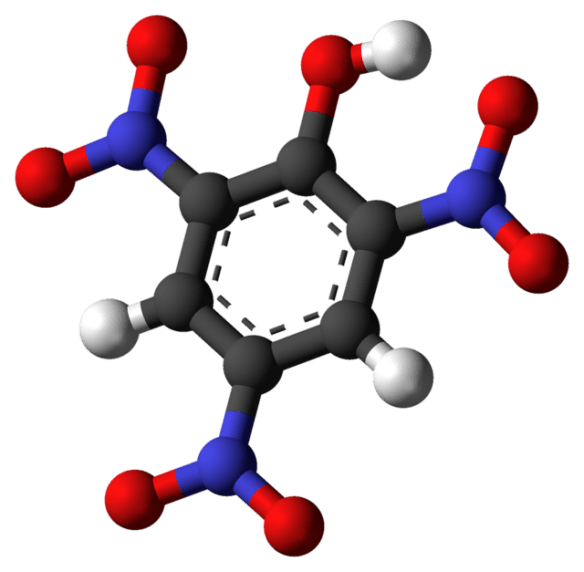

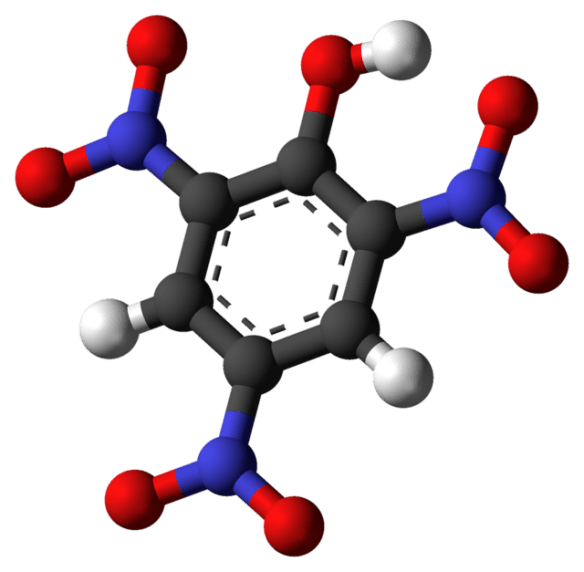

There are hundreds of different acids, and I doubt anyone knows them all. When I encountered a hand-labeled jar reading “picric acid,” I had never heard of that chemical, the structure for which is shown above. When I looked it up, I learned picric acid is safe if it is all in solution with water, but is a shock-sensitive explosive in solid form. I examined the liquid carefully, without actually touching the container. Sure enough, solid crystals had already started to form, over the years, as some of the water in the container slowly evaporated, and escaped.

Great, I thought, sarcastically — a shock-sensitive explosive. I then kept reading the hazard alerts, and noticed that they stated that picric acid should never be stored in any container with a metallic lid, because that invites the formation of explosive metal picrates which can be detonated simply by the friction caused by an attempt to open the lid. The picric acid I was dealing with, of course, not only had the dangerous solid crystals — it also had a metal lid, and a partially corroded one at that.

I never so much as touched that lid. Very carefully, I gently carried this container to the new stockroom, gave it a shelf all by itself, and didn’t so much as give it a nasty look, for the rest of the time I taught there. Leaving it alone, with me being the only person with access to that room, was the safest thing I could think of to do, as long as I was teaching there. For six school years, since it was carefully undisturbed, the picric acid behaved itself — and then, seeking a higher salary, I found a job for the following Fall, teaching at a public school. I knew I would not be able to leave this private school, though, without dealing with this picric acid problem once and for all, along with other dangerous chemicals the school did not need. I could have simply turned my keys in, and left, but that would have risked a potentially-fatal explosion in that school in future years, for I could not safely assume the next chemistry teacher would be familiar with, nor research, picric acid. My conscience would not permit that.

The school year being over, I went to see the school’s new principal. Unlike his predecessor, the new principal had never taught chemistry, but he’d been on the faculty, before his promotion, for longer than I had been there, and so we knew each other well. When I went into his office, with my keys, for end-of-the-year checkout, and calmly told him that there were many serious toxins and an unexploded bomb down the hall, he knew immediately that I wasn’t joking. With his permission, I kept my keys into the beginning of the Summer, getting things ready for professional chemical-disposal experts to come in and remove the dangerous materials. Before long, four cardboard boxes had been filled with dangerous chemicals the school did not need, slated for disposal — and that’s after I had already disposed of most things that needed to go, if I had the knowledge, and means, to dispose of them properly.

The first group of professionals who were called in, for help, were from the local fire department. They took some of the chemicals away, without charge, but only the ones that they knew how to deal with safely. The principal and I were informed that, for the remaining chemicals (down to one box now, in which was the picric acid), a professional “hazmat” team would need to be called in, and it wouldn’t be cheap.

It wasn’t. The bill from the hazmat team exceeded US$2000. They took away three or four kilograms of mercury, as well as a lot of other nasty stuff, but also told us, with apologies, that they weren’t taking the picric acid, it being too dangerous for a “mere” professional hazmat team. To get rid of that, we were told, we’d need to call in the bomb squad from the state’s capital city, Little Rock.

I had heard the phrase “bomb squad” in movies, and on TV, but not in real life. Judging from the look on his face, the same can be said for the principal. As it happened, I wasn’t in town on the day the bomb squad came to school, but I did hear numerous first-hand accounts of what transpired, when I came back the following day to turn in my keys.

One of many surprises reported to me by these witnesses is that the FBI arrived with the bomb squad, asking questions and interviewing people. Apparently there wasn’t supposed to be any picric acid in Arkansas schools, for a statewide sweep had been made to gather it all up, and dispose of it, in the 1970s. My guess, and that’s all it is, is that this very old bottle had been overlooked because of it being in a private, rather than a public, school. If the FBI wants to contact me now to ask me questions about this stuff, I’ll answer them, but, at the time, I didn’t mind a bit that I missed out on the interrogation-portion of these events. After the FBI had finished their on-site investigation, the bomb squad began their work.

This K-12 school has a very large campus, with multiple buildings, and my classroom was at one corner of it. The disposal site they chose — the nearest area sufficiently remote from people and buildings — was far behind the gymnasium, at least half a kilometer away, at the opposite corner of the campus. As it was described to me, two bomb squad guys put on what I call “moon suits,” wrapped the picric acid bottle up, with a lot of padding, and placed this padded bundle on a stretcher. They then walked the stretcher, with its deadly cargo, around and between buildings, across railroad tracks and a street, around the gymnasium, and back into an empty lot, where a deep hole was dug. One of the guys in moon suits then put the picric acid container at the bottom of the hole, along with a stick of dynamite, the idea being to use the smaller dynamite explosion to trigger the much larger explosion of the picric acid.

The bomb-squad “astronaut” lit the long fuse on the dynamite, and scrambled out of the hole as quickly as his moon suit would permit. The fuse burned, right up to the dynamite — and then, just as everyone expected a deafening explosion, it fizzled out. They had unknowingly used a stick of dynamite with a defective fuse.

After waiting a while, just to give the dynamite time to, well, change its “mind” about exploding (which didn’t happen), the suited-up bomb squad guy was sent back into the hole, with a second stick of dynamite, which he placed next to the first one. I hope he got paid extra for this, for I would have quit, immediately, rather than re-enter that hole. He, however, did enter, lit the second dynamite stick, and got out in time. This time, the detonation was successful, and the picric acid and both sticks of dynamite were utterly obliterated.

At the time of the explosion, a former student of mine, who had graduated from this same school a few years before, was working in an office building, three or four kilometers away. I got an e-mail from him, and laughed when I read it. Apparently the entire building he was working in had just been shaken by an explosion in the direction of his former school, and he had one question for me: had I had anything to do with this? I laughed, and replied with an honest answer.