I just spent a couple of hours playing with triangles, their centers, and related things, using Geometer’s Sketchpad. Much of what I found was already known, but some of the things I found may not be. It will take more research to sort out which is which.

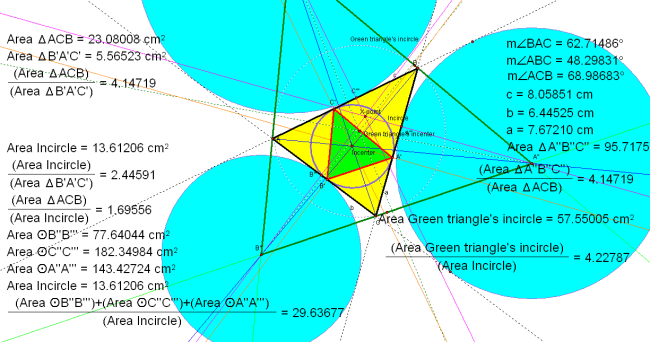

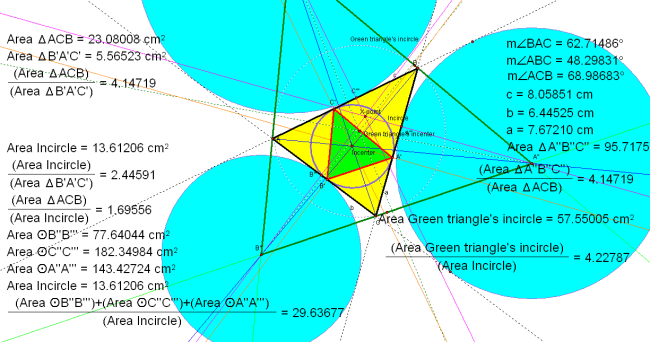

This is where I started. My original triangle, ABC, has heavy black sides and a yellow interior. The sides of ΔABC are extended as black dashed lines. I constructed ΔABC’s three angle bisectors to find its incenter, then constructed perpendicular lines to each side of the triangle from the incenter to find the three “touchpoints,” called A’, B’, and C’, allowing me to construct the incircle of my starting triangle. I also wanted the three excircles, and they are centered at A”, B”, and C” — the three excenters of triangle ABC. These points are found by bisecting all exterior angles of the original triangle, and then looking for the three point of concurrency among themselves, and the three interior angle bisectors previously used to locate the incenter. The heavy green, large triangle is the triangle which connects the three excenters, and probably has an established name, but I couldn’t find it — so I’ll just be calling it the “green triangle.” It is not to be confused with the small triangle in the diagram’s center, which has red sides and a green interior. This small triangle is simply formed by connecting the touchpoints A’, B’, and C’, and has several names already: the Gergonne triangle, the contact triangle, and the intouch triangle of ΔABC.

I set this up in such a way that I could move points A, B, and C around, and watch what happened to angle measures, segment lengths, areas, and area ratios. The picture above shows what happens near regularity, with all three interior angles very close to 60°. This is how I learned that certain area ratios are at a minimum when the triangle is equilateral — as you’ll see, they are all larger in subsequent pictures. At regularity, the green triangle has an area exactly four times that of the original triangle, which, in turn, has an area four times larger than the Gergonne triangle — and, away from regularity, these two area ratios remain equal to each other.

I also found that the green triangle’s incircle’s area is, at minimum, four times that of the original triangle’s incircle — but if you deviate from regularity even slightly, it can be seen that this “just above four” is not equal to the “just above four” area ratios described at the end of the last paragraph.

I also tried adding the areas of all three excircles, then dividing this sum by the area of the incircle. At regularity, this ratio is 27, so each excircle would have exactly nine times the area of an incircle for an equilateral triangle. From that, it follows that an equilateral triangle’s excircle’s radius is three times that of the radius of the incircle. These numbers are minimums; the get bigger if the triangle deviates from regularity in any way.

This second picture shows what happens when regularity is abandoned. I noticed that the green triangle’s incenter, the original triangle’s incenter, and a third point of concurrency I am calling the “x-point” (because I suspect it already has a name, but I don’t know what that name is) appeared as if they might be collinear — but might not be. I checked, and they are non-collinear. I then decided to investigate this x-point further. The x-point is the one point of concurrency of the three lines, one for each excircle, which contain that excircle’s center, as well as the point of tangency between that excircle and the original triangle.

To investigate this x-point further, I started locating other triangle centers, and also continued moving A, B, and C around. The picture above shows the Gergonne point added to the diagram. The Gergonne point is a point of concurrency of three lines — each being a line containing a triangle’s vertex, and the touchpoint opposite that vertex. As you can see, these points still refused to line up. I therefore decided to go all-out, and add many more triangle centers.

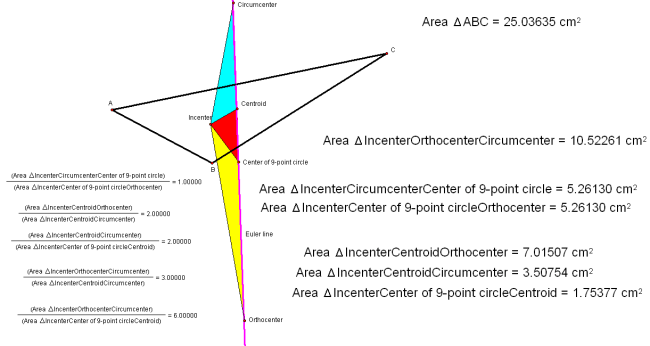

In this last picture, I’ve added the circumcenter (point of concurrence of the triangle’s sides’ three perpendicular bisectors), centroid (point of concurrence of the three medians), orthocenter (point of concurrence of the lines containing the triangle’s three altitudes), and several other things for which you can easily find definitions on Wikipedia — such as the 9-point circle, its center, the Nagel point, the Nagel line, and the Euler line. As you can see, the Euler Line (shown as a heavy orange line) passes through the orthocenter, the center of the nine-point circle, the centroid, and the circumcenter. It does not, however, contain the incenter. What does? The Nagel line (shown in heavy purple), for one thing, which also holds the Nagel point, as well as the centroid, where it intersects the Euler line.

Neither the Euler line nor the Nagel line contains the x-point I was investigating, though — but I found a line which does. It is shown in heavy grey, and passes through (in addition to the x-point) the circumcenter (where it intersects the Euler line) and the Gergonne point, which was completely unexpected. I suspect this line has already been discovered and named, but, until I find out what that name is, I’m calling it the “x-line.”

If anyone who reads this knows more about the x-point or x-line, such as their already-existing names (assuming they’ve been discovered before), please leave this information in a comment here.