In which direction is the polyhedron above rotating? If you say “to the left,” you’re describing the direction faces are going when they pass right in front of you, on the side of the polyhedron which faces you. However, “to the left” won’t really do . . . for, if you consider the faces hidden on the side facing away from you, they’re going to the right. What’s more, both of these statements reverse themselves if you either turn your computer over, or stand upside-down and look at the screen. Also, if you do both these things, the situation re-reverses itself, which means it reverts to its original appearance.

In which direction is the polyhedron above rotating? If you say “to the left,” you’re describing the direction faces are going when they pass right in front of you, on the side of the polyhedron which faces you. However, “to the left” won’t really do . . . for, if you consider the faces hidden on the side facing away from you, they’re going to the right. What’s more, both of these statements reverse themselves if you either turn your computer over, or stand upside-down and look at the screen. Also, if you do both these things, the situation re-reverses itself, which means it reverts to its original appearance.

Rotating objects are more often, however, described at rotating clockwise or counterclockwise. Even that, though, requires a frame of reference to be made clear. If one describes this polyhedron as rotating clockwise, what is actually meant is “rotating clockwise as viewed from above.” If you view this spinning polyhedron from below, however, it is spinning counterclockwise.

Since I live on a large, spinning ball of rock — of all solid objects in the solar system, Earth has the greatest mass and volume, both — I tend to classify rotating objects as having Earthlike or counter-Earthlike rotation, as well. Most objects in the Solar system rotate, and revolve, in the same direction as Earth, and this is consistent with current theoretical models of the formation of the Solar system from a large, rotating, gravitationally-contracting disk of dust and gas. The original proto-Solar system rotated in a certain direction, and the conservation of angular momentum has caused it to keep that same direction of spin for billions of years. Today, it shows up in the direction that planets orbit the sun, the direction that most moons orbit planets, and the direction that almost everything in the Solar system rotates on its own axis. Because one direction dominates, astronomers call it the “prograde” direction, with the small number of objects with rotation (or revolution, in the case of orbital motion) in the opposite direction designated as moving in the “retrograde” direction.

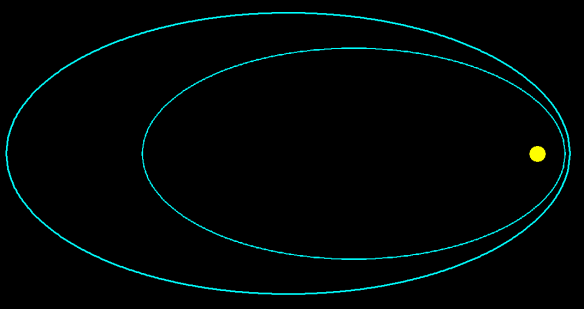

So which is which? Which non-astronomical directional terms, as used above when describing the spinning polyhedron there, should be used to describe the prograde rotation of Earth, its prograde orbital revolution around the sun, and the numerous other examples of prograde circular or elliptical motion of solar system objects? And, for the few “oddballs,” such as Neptune’s moon Triton, which non-astronomical terms should be used to describe retrogade motion? To find out, let’s take a look at Earth’s revolution around the Sun, and the Moon’s around the Earth, for those are prograde is well. This diagram is not to scale, and the view is from above the Solar, Terran, and Lunar North poles.

[Image found reblogged on Tumblr, creator unknown.]

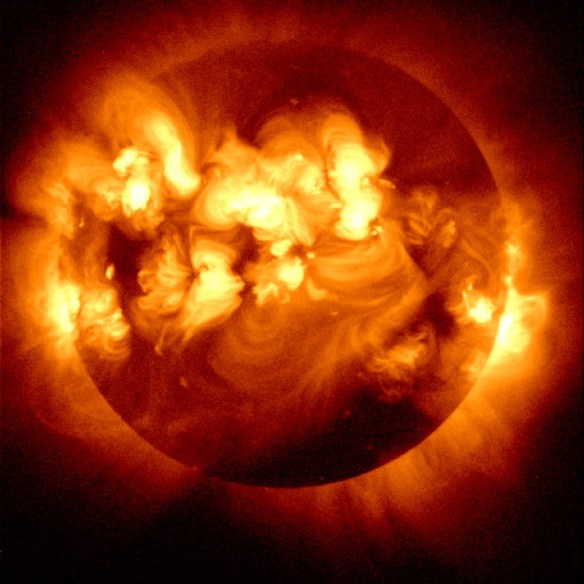

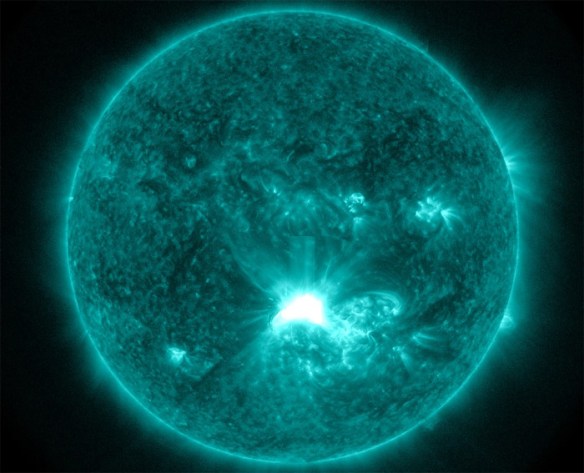

Prograde (Earthlike) motion, then, means “counterclockwise, as viewed from above the North pole.” To describe retrograde (counter-Earthlike) motion, simply substitute “clockwise” for “counterclockwise,” or “South pole” for “North pole,” but not both. Here’s the spinning Earth, as viewed from the side:

[Image source: http://brianin3d.wordpress.com/2011/03/17/animated-gif-of-rotating-earth-via-povray/ ]

If you’ll go back and check the polyhedron at the top of this page, you’ll see that its spin is opposite that of this view of the Earth, and it was described as moving clockwise, viewed from above. That polyhedron, and the image of Earth above, would have the same direction of rotation, though, if either of them, but not both, were simply viewed upside-down, relative to the orientation shown.

Stella 4d, the software I use to make rotating polyhedral .gifs (such as the one that opened this post), then, has them spin, by default, in the same direction as the Earth — if the earth’s Southern hemisphere is on top! As I live in the Northern hemisphere, I wondered if that was deliberate, for the person who wrote Stella 4d, available at www.software3d.com/Stella.php, lives in Australia. Not being shy, I simply asked him if this were the case, and he answered that it was a 50/50 shot, and simply a coincidence that it came out the way it did, for he had not checked. He also told me how to make polyhedral .gifs which rotate as the Earth does, at least with the Northern hemisphere viewed at the top: set the setting of Stella 4d to make .gifs with a negative number of rotations per .gif-loop. Sure enough, it works. Here’s an example of such a “prograde” polyhedron: