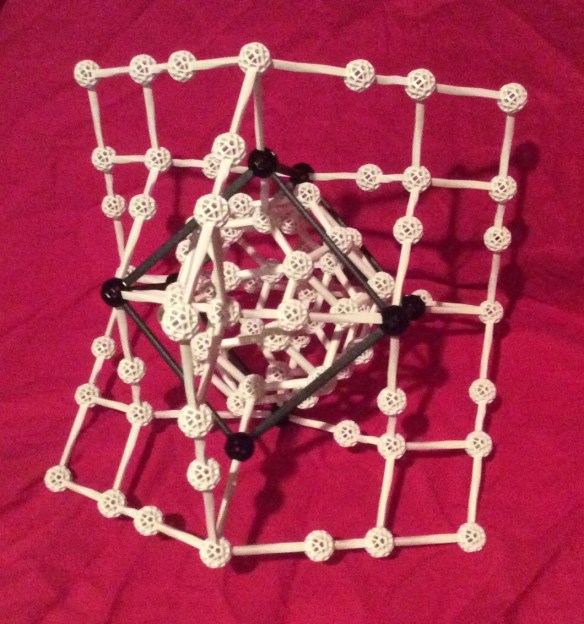

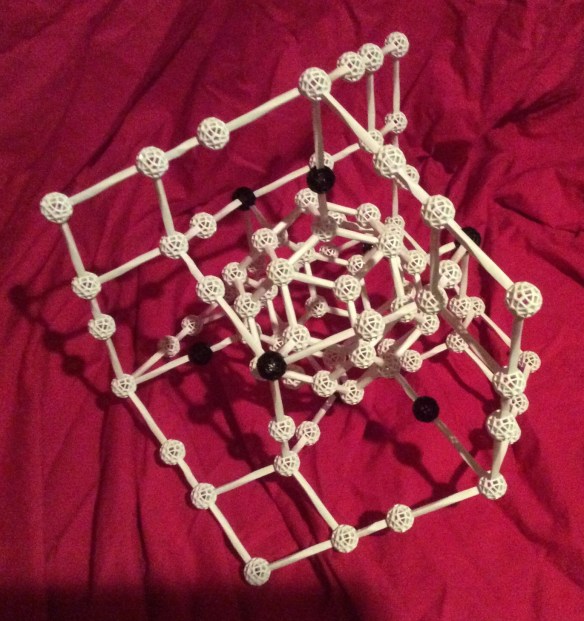

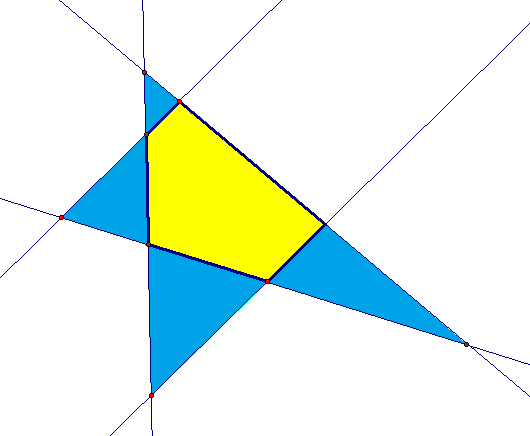

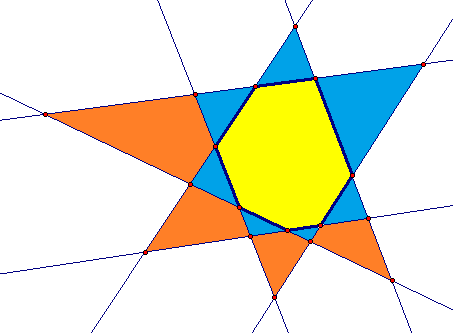

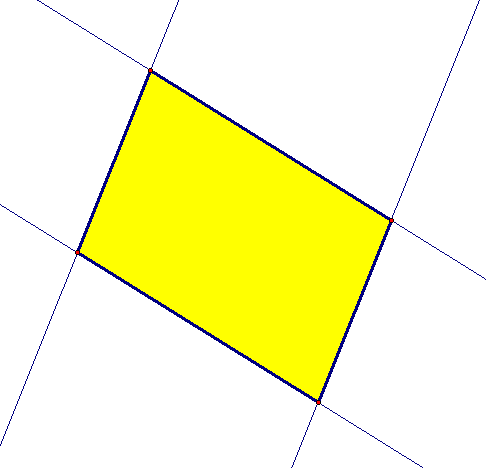

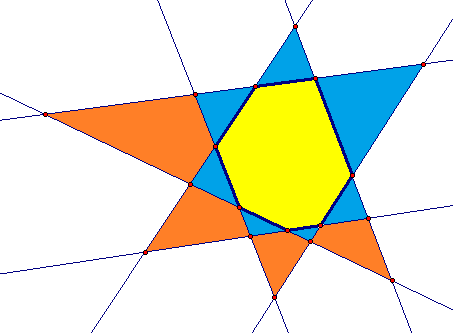

A few days ago, I came across the phrase, while surfing the Internet, “the extended quadrilateral has six vertices.” Not understanding this, I researched the matter, and found out what this phrase means. If the normal four vertices of a quadrilateral are placed such that the quadrilateral has no parallel sides, then two additional vertices are created when the four sides are extended as lines, as shown below. This gives a total of six vertices for this extended quadrilateral.

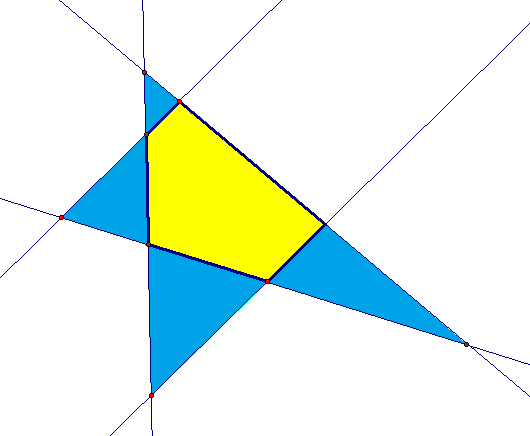

Of course, one need not position the vertices in this way. Trapezoids, by definition, have one pair of parallel sides. The non-parallel sides of an extended trapezoid still intersect outside this quadrilateral, creating a five-vertex situation.

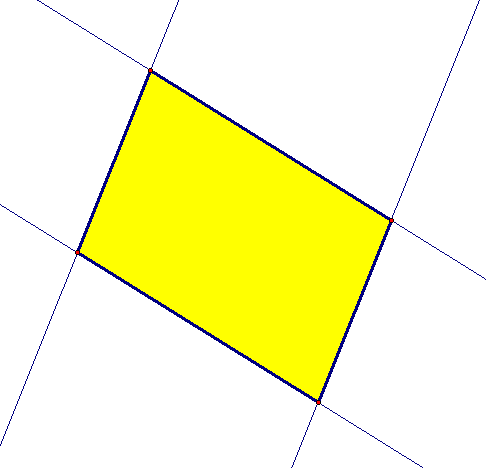

The other option is the parallelogram, with two pairs of parallel sides. This eliminates additional vertices altogether, so there are only four.

This exhausts the possibilities, so the possible numbers of vertices for extended quadrilaterals are 4, 5, and 6.

Realizing this, of course, just raises other questions: what about other extended convex polygons? What are the numbers of possible intersections for such polygons with varying numbers of sides? Is there a pattern? To investigate this, I needed data, and started by taking a step back from quadrilaterals, to briefly consider extended triangles.

Extending the sides of any triangle creates no additional vertices, beyond the three which exist before the extension. This is a result of the fact that three is the maximum number of intersections created by three coplanar lines. Three is, therefore, for triangles, the only answer.

The next step: consider extended convex pentagons. I decided to start by maximizing the number of vertices, by having no parallel sides at all.

As you can see above, this produces ten vertices — five for the non-entended pentagon, plus five more formed by the entensions. To reduce this number, I simply moved vertices of the original, non-extended pentagon to eliminate external vertices, one at a time, by creating pairs of parallel sides.

With one pair of parallel sides, as shown above, the number of vertices is reduced by one, from ten to nine.

For pentagons, the maximum number of pairs of parallel sides is two, as shown above, which lowers the total number of vertices to eight. For pentagons, then, there are three solutions to this puzzle: 8, 9, and 10.

Next, I considered hexagons.

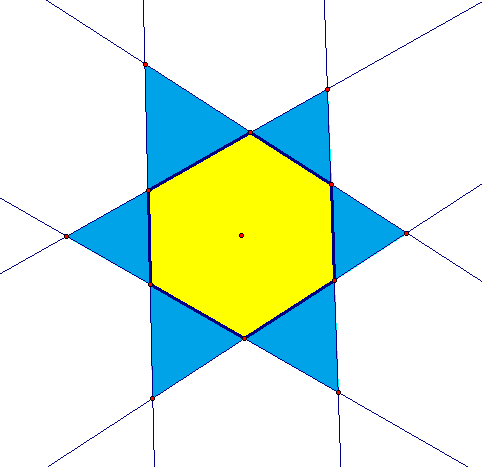

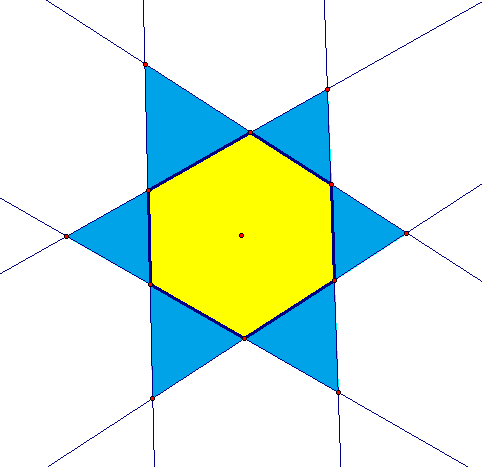

The extended hexagon above has no parallel sides, which gives it the maximum number of vertices: fifteen. In the figure below, by contrast, there is one pair of parallel sides, reducing this number to fourteen.

With two pairs of parallel sides, as shown above, this number again decreases by one, to thirteen. Three pairs of parallel sides is the maximum for hexagons, and is shown below; for this extended hexagon, there are twelve vertices.

For hexagons, then, there are four solutions: 15, 14, 13, and 12.

Still needing more data, I next investigated extended convex heptagons. With no parallel sides at all, as shown below, the total number of vertices is twenty-one.

If only one pair of parallel sides exist, there is one less vertex than the previous answer gave, and this number is twenty, as shown above. It is also possible for there to be two pairs of parallel sides, as shown below, and this yields nineteen vertices.

For heptagons, there is only one other option: three pairs of parallel sides. (A fourth pair would require eight sides.) This situation is shown below, and in it, there are eighteen vertices.

For heptagons, then, the solutions are four in number: 18, 19, 20, and 21.

Next: octagons. With no sides parallel, to obtain the maximum number of vertices (as shown below), there are twenty-eight of them.

In the diagram below, the solution immediately above is reduced by one, to twenty-seven, by making one pair of sides parallel.

The next solution is shown below, and is twenty-six. This is accomplished by making two pair of sides parallel.

To obtain twenty-five vertices, three pairs of sides are made to be parallel, as shown below.

Finally, twenty-four vertices, the minimum for octagons, requires all four pairs of opposite sides to be parallel. This solution is shown below.

Octagons, then, have five solutions: 24 to 28, inclusive.

Here is the data gathered above, in the form of a table, along with additional data obtained by extrapolation, work shown toward a generalized solution, and then that generalized solution itself, in three parts: one for triangles, one where the number of sides is even, and one where n, the number of sides, is odd, with n > 3.