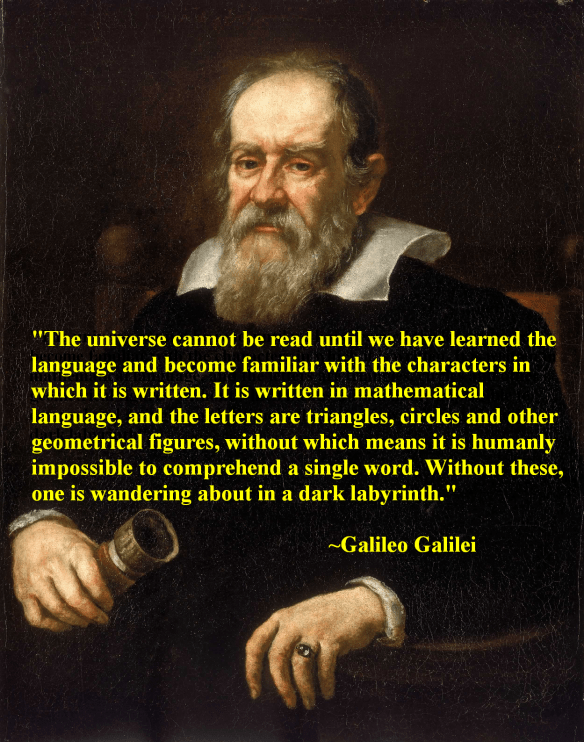

Given the name of this blog, and the familiarity of the number pictured above, I’m sure you recognize it as the beginning of my favorite number, pi. On various websites, you can find far more digits than are shown above. However, just the digits shown in the top row here are greater in number than that needed for any real-world, practical application. Is pi useful? Is mathematics itself useful? Of course they are . . . but those questions miss the point entirely.

Every teacher who has been in the field for long has heard the complaint, disguised as a question, “What are we ever going to use this for?” Unfortunately, most school systems, as well as teacher-training programs, have chosen to respond to this well-known complaint by repeatedly telling teachers, and teachers-in-training, that it is of extreme importance to show students how the curriculum is “relevant,” and adjust curricula to make them more so. This usually boils down, of course, to trying to convince students that learning is important because, supposedly, education = a better job in the future = more money. Sometime this “equation” works, and sometimes it does not, but it always misses a key point, one that should not be left out, but too often is.

It is a fallacy that learning has to have a practical application to be a worthwhile endeavor. There’s more to life than the fattening of bank accounts. Sadly, many of those making decisions in education do not realize this. Their attempts to reduce education to a strictly utilitarian approach are causing great harm.

This scenario has happened many times: a mathematician discovers an elegant proof to a surprising theorem, a physicist figures out something previously unknown about the nature of reality, or a researcher in another field does something comparable, and someone then asks them, “But what can this be used for?” On occasion, tired of hearing this utilitarian refrain, such researchers give unusually honest responses which surprise and confuse many people — such as, “Someone else might, at some point, find a practical application for this . . . but I sincerely hope that never happens.” Such a response is rarely understood, but it makes the person who says it feel better to vent some of their frustration with those who are obsessed with tawdry, real-world applications for everything.

Many humans — and this is a terrible shame — live almost their entire lives like rats in mazes, running down passages and around corners, chasing tangible rewards — cheese for the rats, or the ability to buy, say, a fancy new car, in the case of the people. People shouldn’t live like lab rats . . . and, unlike lab rats, we don’t have to. People are smart enough to find higher purposes in life. People can, in other words, find, understand, and appreciate beauty — in things which are useless, in the sense that they have no useful applications. We can appreciate things that transcend mere utility, if we choose to do so.

Much of life is utterly banal, for a great many people. They wake up each day, work themselves into exhaustion at horribly boring jobs, go home, numb themselves with television, massive alcohol consumption, or other hollow pursuits, fall asleep, and then get up and repeat the process the next day . . . and then they finally get old and die. Life can be so much more than that, though, and it should be.

The researchers I described earlier aren’t doing what they do for money, or even the potential for fame. Are such things as mathematics and physics useful? Yes, they are, but that isn’t why pure researchers do them. The same can be said for having sex: it’s useful because it produces replacement humans, but that isn’t why most people do it. People have sex, obviously, because they enjoy it. In simpler terms: it’s fun. Most people understand this concept as it relates to sex, but far fewer understand it when it relates to other aspects of life, particularly those of an academic nature.

Academic pursuits are of much greater value when the motivation involved is joy, and the fun involved, rather than avarice. As scrolling through this blog will show you, I enjoy searching for polyhedra which have not been seen before. I certainly don’t expect to get rich from any such discoveries I make in this esoteric branch of geometry, which is itself one subfield, among many, in mathematics. I do it because it is fun. It makes me happy.

Much of life is pure drudgery, but our lives can be enriched by finding joyous escapes from our routines. An excellent way to do that is to learn to appreciate the beauty of uselessness — uselessness of the type that elevates the human spirit, in a way that the pursuit of material goods never can.

This is the approach we should encourage students to have toward education. Learning is far too valuable an activity to be limited, in its purpose, to the pursuit of future wealth. It’s time to change our approach.