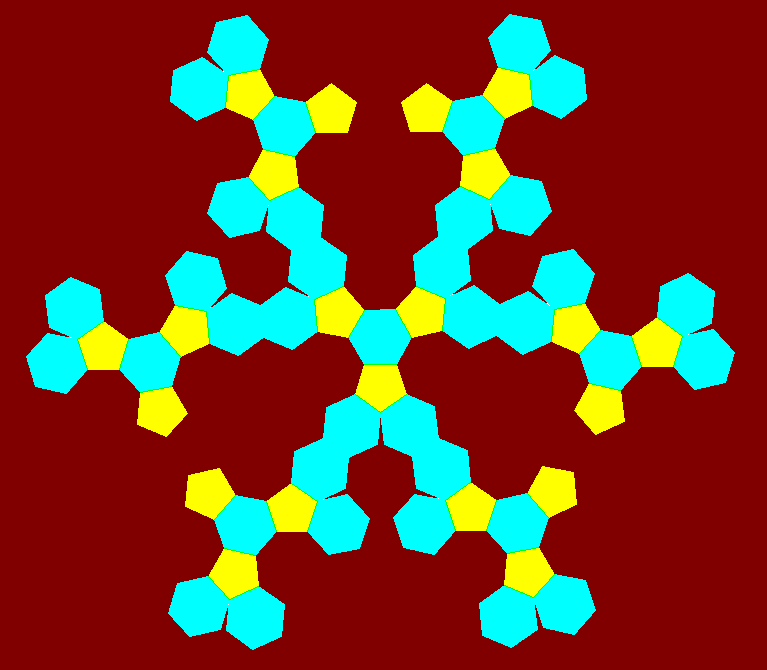

I call the polyhedron above the rhombcuboctahedron. Other names for it are the rhombicuboctahedron (note the “i”), the small rhombcuboctahedron, and the small rhombicuboctahedron. Sometimes, the word “small,” when it appears, is put in parentheses. Of these multiple names, all of which I have seen in print, the second one given above is the most common, but I prefer to leave the “i” out, simply to make the word look and sound less like “rhombicosidodecahedron,” one of the polyhedra coming later in this post.

My preferred name for this polyhedron is the great rhombcuboctahedron, and it is also called the great rhombicuboctahedron. The only difference there is the “i,” and my reasoning for preferring the first name is the same as with its “little brother,” above. However, as with the first polyhedron in this post, the “i”-included version is more common than the name I prefer.

Unfortunately, this second polyhedron has another name, one I intensely dislike, but probably the most popular one of all — the truncated cuboctahedron. Johannes Kepler came up with this name, centuries ago, but there’s a big problem with it: if you truncate a cuboctahedron, you don’t get square faces where the truncated parts are removed. Instead, you get rectangles, and then have to deform the result to turn the rectangles into squares. Other names for this same polyhedron include the rhombitruncated cuboctahedron (given it by Magnus Wenninger) and the omnitruncated cube or cantitruncated cube (both of these names originated with Norman Johnson). My source for the named originators of these names is the Wikipedia article for this polyhedron, and, of course, the sources cited there.

This third polyhedron (which, incidentally, is the one of the thirteen Archimedean solids I find most attractive) is most commonly called the rhombicosidodecahedron. To my knowledge, no one intentionally leaves out the “i” after “rhomb-” in this name, and, for once, the most popular name is also the one I prefer. However, it also has a “big brother,” just like the polyhedron at the top of this post. For that reason, this polyhedron is sometimes called the small rhombicosidodecahedron, or even the (small) rhombicosidodecahedron, parentheses included.

I call this polyhedron the great rhombicosidodecahedron, and many others do as well — that is its second-most-popular name, and identifies it as the “big brother” of the third polyhedron shown in this post. Less frequently, you will find it referred to as the rhombitruncated icosidodecahedron (coined by Wenninger) or the omnitruncated dodecahedron or icosahedron (names given it by Johnson). Again, Wikipedia, and the sources cited there, are my sources for these attributions.

While I don’t use Wenninger’s nor Johnson’s names for this polyhedron, their terms for it don’t bother me, either, for they represent attempts to reduce confusion, rather than increase it. As with the second polyhedron shown above, this confusion started with Kepler, who, in his finite wisdom, called this polyhedron the truncated icosidodecahedron — a name which has “stuck” through the centuries, and is still its most popular name. However, it’s a bad name, unlike the others given it by Wenninger and Johnson. Here’s why: if you truncate an icosidodecahedron (just as with the truncation of a cuboctahedron, described in the commentary about the second polyhedron pictured above), you don’t get the square faces you see here. Instead, the squares come out of the truncation as rectangles, and then edge lengths must be adjusted in order to make all the faces regular, once more. I see that as cheating, and that’s why I wish the name “truncated icosidodecahedron,” along with “truncated cuboctahedron” for the great rhombcuboctahedron, would simply go away.

Here’s the last of the Archimedean solids with more than one English name:

Most who recognize this shape, including myself, call it the truncated cube. A few people, though, are extreme purists when it comes to Greek-derived words — worse than me, and I take that pretty far sometimes — and they won’t even call an ordinary (Platonic) cube a cube, preferring “hexahedron,” instead. These same people, predictably, call this Archimedean solid the truncated hexahedron. They are, technically, correct, I must admit. However, with the cube being, easily, the polyhedron most familiar to the general public, almost none of whom know, let alone use, the word “hexahedron,” this alternate term for the truncated cube will, I am certain, never gain much popularity.

It is unfortunate that five of the thirteen Archimedean solids have multiple names, for learning to spell and pronounce just one name for each of them would be task enough. Unlike in the field of chemistry, however, geometricians have no equivalent to the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemists), the folks who, among other things, select official, permanent names and symbols for newly-synthesized elements. For this reason, the multiple-name problem for certain polyhedra isn’t going away, any time soon.

(Image credit: a program called Stella 4d, available at www.software3d.com/Stella.php, was used to create all of the pictures in this post.)