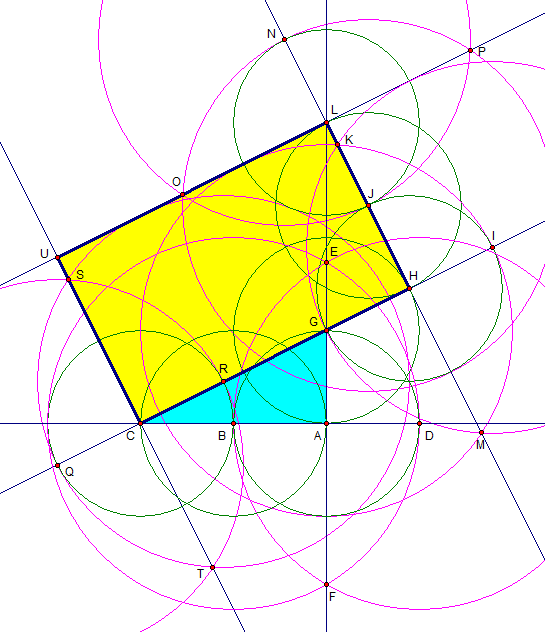

I found the image above through the Wikipedia article on the golden ratio. After using what appears above to define the golden ratio, the article then reveals its exact and approximate values. Later, the writers of the article do show the calculations involved in doing this, but they seem unnecessarily complicated. I’m going to try to simplify the process here, and might later edit/simplify this Wikipedia article to make it more understandable.

So, first, “a + b is to a as a is to b” need to be written as a fraction, which is easy enough: (a + b)/a = a/b. The value of this fraction, a/b, is, by definition, φ, the golden ratio. As an equation, this can be written a/b = φ.

Next, apply cross-multiplication to (a + b)/a = a/b, and it becomes (a + b)(b) = (a)(a), which simplifies to ab + b² = a².

Also, since a/b = φ, this means that a = φb (via the multiplication property). Next, ab + b² = a² is rewritten, with φb substituted for each a. The result of this substitution is (φb)(b) + b² = (φb)², which then becomes φb² + b² = φ²b². To simplify this, b² may be cancelled (via the division property), producing φ + 1 = φ². This may then be rearranged (via the subtraction and symmetric properties) to φ² – φ – 1 = 0. Two values of φ can then be found via the quadratic formula, and they are {1 ± sqrt[1 – (4)(1)(-1)]}/2 = [1 ± sqrt(5)]/2. Use “+,” and calculate a decimal approximation for this irrational number, and you get ~1.618, which is the golden ratio. Use “-” instead, and you get a negative number (approximately -0.618), which can be rejected on the grounds that a ratio of two lengths must be positive, since all lengths, themselves, are positive.

Also, I’m changing my mind regarding changing Wikipedia, on this subject. The two versions of the calculation (the one now on Wikipedia, and mine) don’t match, but both are mathematically valid — and, while my version makes more intuitive sense to me, that doesn’t mean it would make more sense to others, and Wikipedia isn’t there for me alone. Until I actually wrote the calculation out, I thought my version would be simpler, but I cannot claim that now.

[Later addition: see the first comment below for a way, suggested by a reader of this blog, to simplify the calculation, as I wrote it above. I’m not going to take credit for his improvement, of course — that would violate mathematical etiquette!]