As a young child (before I started school), my strong interest in mathematics was always there. No one knew I had Asperger’s at that time, but it is clear to me now, in retrospect, that I was a young “Aspie,” in the early stages of the development of a special interest.

I cannot remember a time without my math-fascination, to the point where I speculate that I was motivated to learn to talk, read, and write English simply to bring more of the mathematics in my head into forms which I could express, and also to gain the ability to research forms of mathematics, by reading about them, which were new to me: negative numbers, fractions, names for extremely large numbers, and so on. I would devour one concept, internalize it, so it could not be forgotten, and quickly move on to my next mathematical “snack.” The shift to geometry-specialization took many years longer; at first, my special interest was simply mathematics in general, to the extent that I could understand it.

I was too young, then, to even understand the difference between actual numbers, and informal numbers I heard others use in conversation, such as zillion, jillion, and especially umpteen, and, armed with this lack of understanding, I endeavored to figure out the properties of these informal numbers. Zillion and jillion were uncountably large: that much seemed clear, although I could never figure out which one was larger. Umpteen, however, seemed more accessible, due to the “-teen” prefix. It seemed perfectly reasonable to me to simplify umpteen to a more fundamental informal number, “ump,” simply by subtracting ten from umpteen, following the pattern I had noticed which connects thirteen to three, seventeen to seven, and so on. This led to the following:

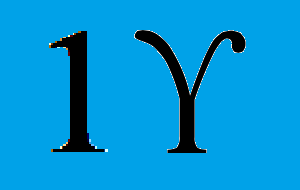

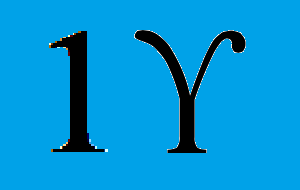

1ϒ – 10 = ϒ (umpteen minus ten equals ump)

I wasn’t using upsilon as a symbol for the informal number “ump” at that age. Rather, I simply needed a symbol, today, to write this blog-post, so I chose one. The capital Greek letter upsilon seems like a good pick. I’m using it more like a digit, here, rather than a variable — although, when I first reasoned this out, over forty years ago, I had not yet learned to distinguish between digits, variables, and numbers, at least not using other peoples’ terms.

Occasionally, I would hear people use ump-based informal numbers (I grew up in Arkansas, you see) which clearly seemed larger than umpteen. One such “number” I heard was, of all things, “umpty-ump.” Well, just how large is umpty-ump? I reasoned that it had to be umpteen minus ten, with this difference then multiplied by eleven.

1ϒ – 10 = ϒ (umpteen minus ten equals ump)

10(ϒ) = ϒ0 (ten times ump equals umpty)

ϒ0 + ϒ = ϒϒ (umpty plus ump equals umpty-ump)

Factoring ump out of the third equation above yields the following:

ϒ(10 + 1) = ϒ(11)

Next, ump cancels on both sides, leaving the following, which is known to be true without the involvement of informal numbers:

10 + 1 = 11

Having figured this out, I would then explain it, at great length, to anyone who didn’t make their escape quickly enough. It never occurred to me, at that age, that there actually are people who do not share my intense interest in mathematics. (Confession: I still do not understand the reason for the shockingly small amount of interest, in mathematics, found in the minds of most people. Why doesn’t everyone find math fascinating, since, well, it is fascinating?)

What I didn’t yet realize is that I was actually figuring out important concepts, with this self-motivated mathematical play: place value in base-ten, doing calculations in my head, some basic algebra, and, of course, the fact that playing with numbers is ridiculously fun. (That last one is a fact, by the way — just in case there is any doubt.)

I did not distinguish play from work at that age, and considered any interruption absolutely unacceptable. This is what I would typically say, if anyone, including my parents, disturbed me while I was working these things out, but was not yet ready to discuss them: “I’m BUSY!”

Everyone who knew me then, I am guessing, remembers me shouting this, as often as I found it necessary.