Someone nudged my shoulder, stirring me from deep sleep. “Wake up, grandpa,” said an unfamiliar voice. Grandpa? Who’s that? I opened my eyes to see a young woman, dressed in black, looking back at me. Her face was brown, and her eyes looked like deep pools of water.

She smiled. Nothing in twenty-plus years of teaching could have prepared me for this, I thought. I looked around, trying to find my cell phone, without success. Nothing here was like anything I’d seen before. Small lights, like fireflies, circled us in the darkness.

“I know it’s confusing to be called ‘grandpa,'” she said, answering a question I had not yet had the chance to ask. “This is, well, complicated.” Her voice sounded excited, even though she was speaking softly. She reminded me of teachers new to the profession, positively bursting with new ideas, and looking forward, enthusiastically, to the new school year ahead.

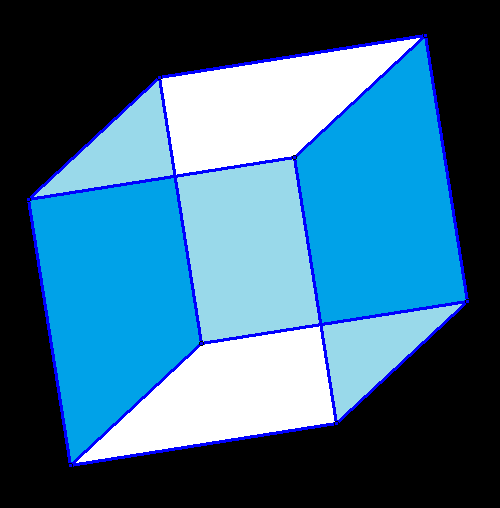

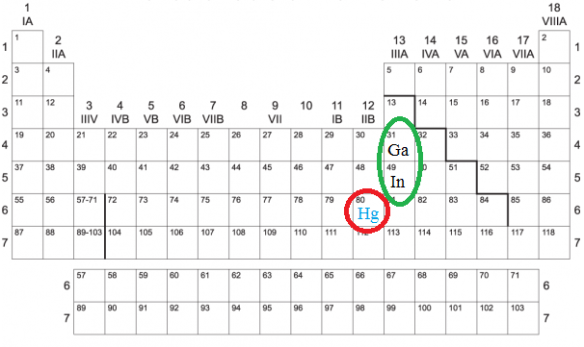

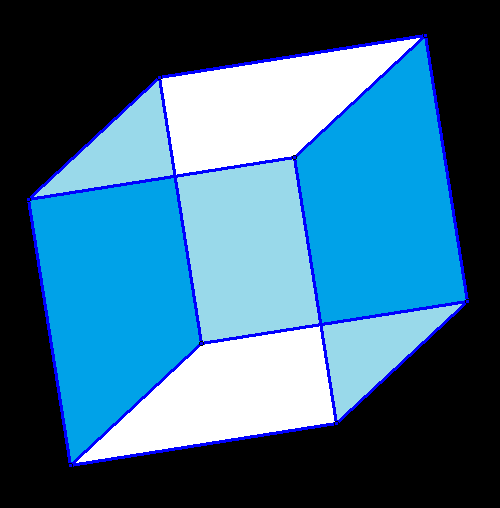

“It would have to be complicated,” I mumbled. Sleep was fading as I rubbed my eyes, trying to see where I was. A light came on, but it was unclear where the lightbulbs were. We were alone, inside a blue and white cube. The cube slowly moved, but its direction kept changing. “What am I doing here? Where’s my wife? Where am I, and who are you?”

“So many questions! I expected that, though. I will explain what I can.”

“That’s good, because . . . .”

“Please don’t interrupt,” she said. I stopped talking, but did not stop thinking. It appeared to be time to listen, not talk. “Thank you,” my alleged granddaughter continued. “In order, here are the answers to your questions. First, you are here for an important conversation. Second, your wife is peacefully sleeping. Third and fourth, you’re in my time-travel cube, and my name is Xiahong Al-Nasr. Technically, you’re my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, but . . . .” I raised my hand to ask a question, as if I were in class myself. She shook her head, and continued, “. . . I’ve always thought of you as, simply, ‘grandpa.’ It’s a time-saver. May I continue explaining why we are here, or can your question wait?”

I thought fast. What should I say next? There was only one logical response. “I’ll listen,” I replied, and put my hand back down.

“You’re about to go back to school,” she said, “and you’re the teacher. It’s important that you understand why you are doing what you do, this year, above all others.” This reminded me of advice I’d heard before, but this time I was listening as if I were hearing for the first time.

This woman’s name, Xiaohong Al-Nasr, combined a Chinese given name with an Arabic surname. I hoped she would explain how that had happened.

“You’re wondering about my name,” she said. I swallowed, and nodded. My mouth was too dry to speak. “I’m from the 23rd Century,” she continued. “Nearly everyone where I work and learn, including me, has DNA from every continent on Earth. I’ve also got a little from off-world colonies, but I’m 100% human, just as you are. I was given my name by all of my parents.” She paused. Her gaze was locked to my own. “I’ve been authorized to tell you that much, but I have to be careful about revealing more, to prevent altering the timestream. Do you believe me?”

“If you know anything about me, you know that I teach science, as well as other subjects.” It was a relief to finally have my turn to speak. My alleged descendant, Xiaohong, was listening to me now. Finally! “You’ve either studied me, somehow, or you’re reading my mind, or it’s something else even more complicated, but you seem to know what I know. You must know, then, that scientists are trained to be skeptical. Everything has to have evidence to support it. In science, there is no higher authority than experiment.”

“I understand that, grandpa. We knew you would need evidence, so I do have a gift for you. It’s a t-shirt. You like t-shirts, after all.” Xiaohong smiled, and removed a small capsule from her pocket, no larger than a quarter. She opened it, and — somehow — pulled a full-size t-shirt from that impossibly small place.

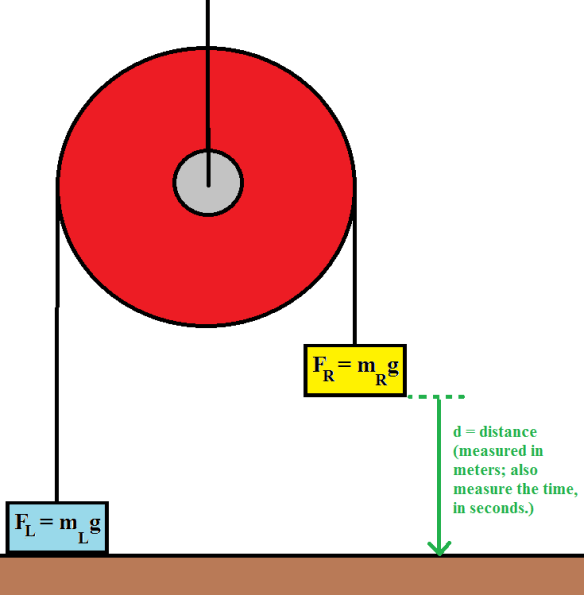

I took the t-shirt from my descendant. Touching it was, well, real! I turned it over. It said “Go Bears!” on the back. Even if I believed her, though, I knew I would need more than just a t-shirt to convince anyone else. After all, time travel to the past was considered impossible by every scientist I had studied. Quickly, I did the arithmetic, using the year on the shirt. “That’s the year I would turn 300 years old, if I could live that long!” I was now catching Xiaohong’s excitement. “Clearly, Arthur C. Clarke’s Three Laws apply here, as does the Sagan Standard, Feynman’s First Principle, the grandfather paradox, and — and — and — the entire scientific method!”

“You’re absolutely correct, and it will be important for your students to understand all those things as well.” She was right; these are all things I talked about in science class, every year. This year, though, I can try to explain them differently, or perhaps have my students research them, and then have the students explain them to my class. Correction: my classes. My students. All of them.

Something fell into place in my mind at that moment, and I finally understood what was going on. It wasn’t my own accomplishments that had brought my descendant back in time to visit me, but the unknown creations of a student of mine — from the school year about to begin. Xiaohong smiled.

“You’ve figured it out, haven’t you?” She was asking a question, and, this time, I had the answer.

“Yes. You came back through time to refocus my attention to my own true purpose in the classroom. My job is to help my students learn to do great things. It’s not about me. It’s about them!” Xiaohong’s smile grew larger. I continued. “This school year is critical. This is true of all school years, in fact. Each year is both important, and urgent. In every school, and for every student, we must always do our best to learn — together.”

Xiaohong extended her hand, and received a firm handshake from me. “Now that you know the truth, grandpa, our work here is finished. You’ll wake up in the morning, in bed with your sleeping wife, and after that, you’ll find your t-shirt, in the dryer, at home. I have to go, though; I’m needed back in the 23rd Century. After all, I have my own classes to teach, quite soon, at our Time Travel Academy, where I got your t-shirt. Goodbye, and have a great school year! I know I will, as I continue my training to become a teacher myself.”

“I will do that,” I replied. “Thank you so much! As for this evidence you’ve given me, I know how I’ll handle that. I will let the students evaluate it, with help from me, on an ‘as needed’ basis.”

“Exactly,” Xiaohong said, and then she spoke to the ceiling of her time travel cube. “Send us both back to where we were — now.” A humming sound started, then became louder. The lights began to dim. After a few minutes, everything faded to darkness, and silence, once more.

When I awoke, home again, I checked the dryer, and found it — my t-shirt from the future — waiting for me. This school year will be amazing!