On numerous occasions, I have repeated this experiment, in keeping with the scientific method. I have obtained the same null result as Carlin obtained, each and every time.

On numerous occasions, I have repeated this experiment, in keeping with the scientific method. I have obtained the same null result as Carlin obtained, each and every time.

Because of the price of silver being literally on fire, they will not be buying and selling troy ounces of metallic silver when the markets open in New York tomorrow morning. Instead, they will be selling “oxide ounces” of silver oxide, in sealed-plastic capsules of this black powder, with an oxide ounce of silver oxide being defined as that amount of silver oxide which contains one troy ounce of silver.

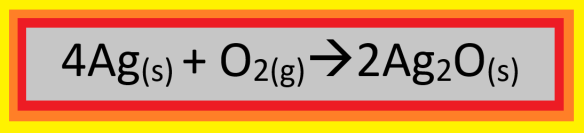

A troy ounce of silver is 31.1 grams of that element, which has a molar mass of 107.868 g/mole. Therefore, a troy ounce of silver contains (31.1 g)(1 mol/107.868 g) = 0.288 moles of silver. An oxide ounce of silver oxide would also contain oxygen, of course, and the formula on the front side of a silver oxide capsule (shown above; information on the back of the capsule gives the number of oxide ounces, which can vary from one capsule to another) is all that is needed to know that the number of moles of oxygen atoms (not molecules) is half the number of moles of silver, or (0.288 mol)/2 = 0.144 moles of oxygen atoms. Oxygen’s non-molecular molar mass is 15.9994 g, so this is (0.144 mol)(15.9994 g/mol) = 2.30 g of oxygen. Add that to the 31.1 g of silver in an oxide ounce of silver oxide, and you have 31.1 g + 2.30 g = 33.4 grams of silver oxide in an oxide ounce of that compound.

In practice, however, silver oxide (a black powder) is much less human-friendly than metallic silver bars, coins, or rounds. As you can easily verify for yourself using Google, silver oxide powder can, and has, caused health problems in humans, especially when inhaled. This is the reason for encapsulation in plastic, and the plastic, for health reasons, must be far more substantial than a mere plastic bag. For encapsulated silver oxide, the new industry standard will be to use exactly 6.6 g of hard plastic per oxide ounce of silver oxide, and this standard will be maintained when they begin manufacturing bars, rounds, and coins of silver oxide powder enclosed in hard plastic. This has created a new unit of measure — the “encapsulated ounce” — which is the total mass of one oxide ounce of silver oxide, plus the hard plastic surrounding it on all sides, for a total of 33.4 g + 6.6 g = 40.0 grams, which will certainly be a convenient number to use, compared to its predecessor-units.

# # #

[This is not from The Onion. We promise. It is, rather, a production of the Committee to Give Up on Getting People to Ever Understand the Meaning of the Word “Literally,” or CGUGPEUMWL, which is fun to try to pronounce.]

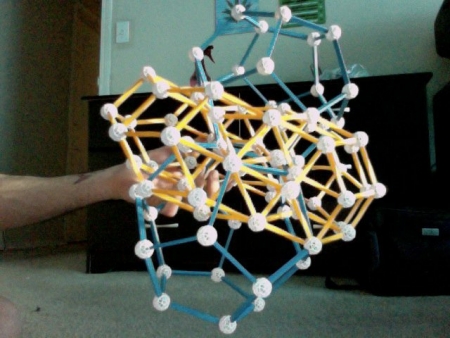

I’ve been using Zometools, available at http://www.zometool.com, to build interesting geometrical shapes since long before I started this blog. I recently found this: a 2011 photograph of myself, holding a twisting Zome torus. While I don’t remember who was holding the camera, I do remember that the torus is made of adjacent parallelopipeds.

After building this torus, I imagined it as an accretion disk surrounding a neutron star — and now I am imagining it as a neutron star on the verge of gaining enough mass, from the accretion disk, to become a black hole. Such an object would emit intense jets of high-energy radiation in opposite directions, along the rotational axis of this neutron star. These jets of radiation are perpendicular to the plane in which the rotation takes place, and these two opposite directions are made visible in this manner, below, as two dodecahedra pointing out, on opposite sides of the torus — at least if my model is held at just the right angle, relative to the direction the camera is pointing, as shown below, to create an illusion of perpendicularity. The two photographs were taken on the same day.

In reality, of course, these jets of radiation would be much narrower than this photograph suggests, and the accretion disk would be flatter and wider. When one of the radiation jets from such neutron stars just happens to periodically point at us, often at thousands of times per second, we call such rapidly-rotating objects pulsars. Fortunately for us, there are no pulsars near Earth.

It would take an extremely long time for a black hole to form, from a neutron star, in this manner. This is because most of the incoming mass and energy (mostly mass, from the accretion disk) leaves this thermodynamic system as outgoing mass and energy (mostly energy, in the radiation jets), mass and energy being equivalent via the most famous formula in all of science: E = mc².

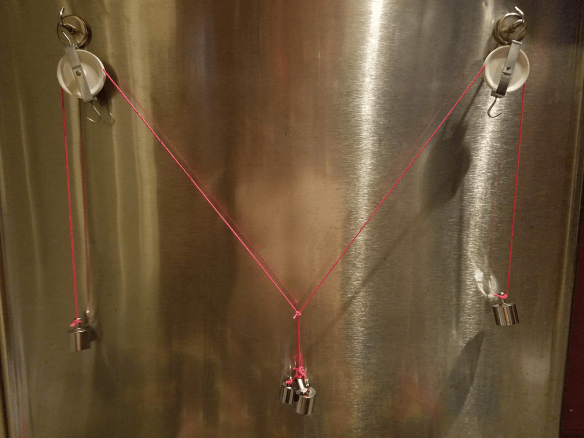

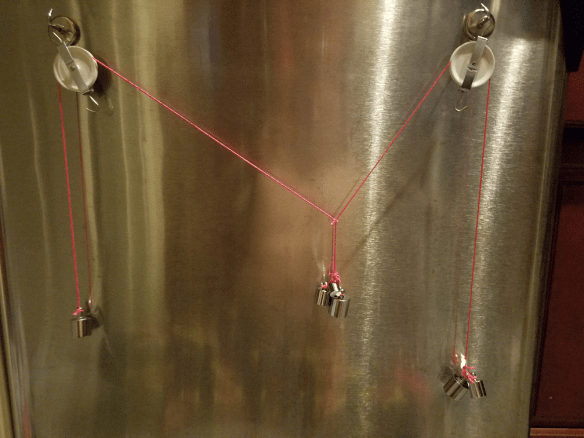

An interesting phenomenon in physics, and physics education, is the simplicity of symmetric situations, compared to the complexity of similar situations which are, instead, asymmetrical. Students generally learn the symmetrical versions first, such as this static equilibrium problem, with the hanging masses on both left and right equal.

The problem is to find the measures of the three angles shown above, with values given for all three masses. Here is the setup, using physical objects, rather than a diagram.

The masses on the left and right are each 100 g, or 0.100 kg, while the central masses total 170 g, or 0.170 kg. Since all hanging masses are in static equilibrium, the forces pulling at the central point (at the common vertex of angles λ, θ, and ρ) must be balanced. Specifically, downward tension in the strings must be balanced by upward tension, and the same is true of tension forces to the left and to the right. In the diagram below (deliberately asymmetrical, since that’s coming soon), these forces are shown, along with the vertical and horizontal components of the tension forces held in the diagonal strings.

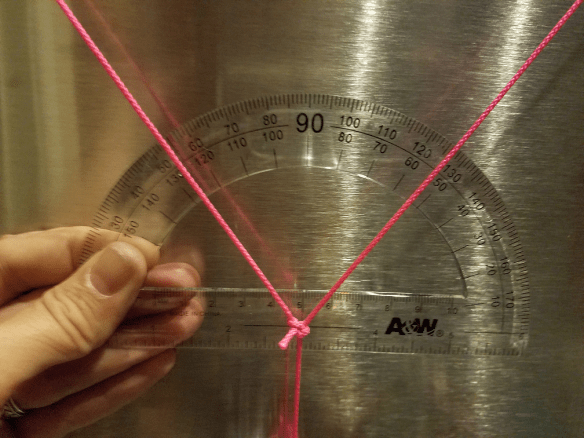

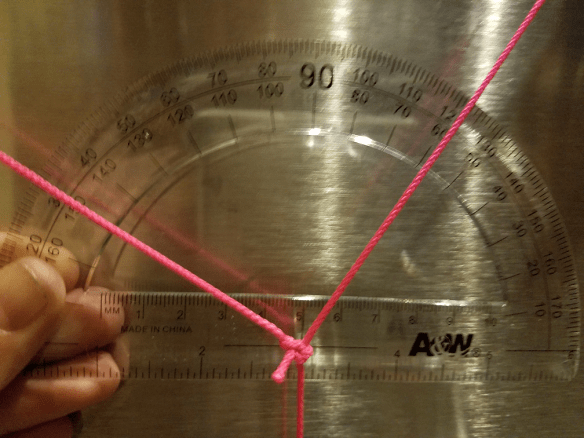

Because the horizontal forces are in balance, Tlx = Trx, so Mlgcosλ = Mrgcosρ — which is not useful now, but it will become important later. In the symmetrical situation, all that is really needed to solve the problem is the fact that the vertical forces are in balance. For this reason, Tc = Tly + Try, so Mcg = Mlgsinλ + Mrgsinρ. Since, due to symmetry, Ml = Mr and λ = ρ, Mr may be substituted for Ml, and ρ may be substituted for λ, in the previous equation Mcg = Mlgsinλ + Mrgsinρ, yielding Mcg = Mrgsinρ + Mrgsinρ, which simplifies to Mcg =2Mrgsinρ. Cancelling “g” from each side, and substituting in the actual masses used, this becomes 0.170 kg = 2(0.100 kg)sinρ, which simplifies to 0.170 kg = (0.200 kg)sinρ, then 0.170/0.200 = sinρ. Therefore, angle ρ = sin-1(0.170/0.200) = 58°, which, by symmetry, must also equal λ. Since all three angles add up to 180º, the central angle θ = 180° – 58° – 58° = 64°. These answers can then be checked against the physical apparatus.

When actually checked with a protractor, the angles on left and right are each about 53° — which is off from the predicted value of 58° by about 9%. The central angle, of course, is larger, at [180 – (2)53]° = 74°, to make up the difference in the two smaller angles. The error here could be caused by several factors, such as the mass of the string itself (neglected in the calculations above), friction in the pulleys, or possibly the fact that the pulleys did not hang straight down from the hooks which held them, but hung instead at a slight diagonal, as can be seen in the second image in this post. This is testable, of course, by using thinner, less massive string, as well as rigidly-fixed, lower-friction pulleys. However, reducing the error in a lab experiment is not my objective here — it is, rather, use of a simple change to turn a relatively easy problem into one which is much more challenging to solve.

In this case, the simple change I am choosing is to add 50 grams to the 100 g already on the right side, while leaving the central and left sides unchanged. This causes the angles where the strings meet to change, until the situation is once more in static equilibrium, with both horizontal and vertical forces balanced. With the mass on the left remaining at 0.100 kg, the central mass at 0.170 kg, and the mass on the right now 0.150 kg, what was an easy static equilibrium problem (finding the same three angles) becomes a formidable challenge.

For the same reasons as before (balancing forces), it remains true that Mlgcosλ = Mrgcosρ (force left = force right), and, this time, that equation will be needed. It also remains true that Mcg = Mlgsinλ + Mrgsinρ (downward force = sum of the two upward forces). The increased difficulty is caused by the newly-introduced asymmetry, for now Ml ≠ Mr, and λ ≠ ρ as well. It remains true, of course, that λ + θ + ρ = 180°.

In both the vertical and horizontal equations, “g,” the acceleration due to gravity, cancels, so Mlgcosλ = Mrgcosρ becomes Mlcosλ = Mrcosρ, and Mcg = Mlgsinλ + Mrgsinρ becomes Mc = Mlsinλ + Mrsinρ. The simplified horizontal equation, Mlcosλ = Mrcosρ, becomes Ml²cos²λ = Mr²cos²ρ when both sides are squared, in order to set up a substitution based on the trigonometric identity, which works for any angle φ, which states that sin²φ + cos²φ = 1. Rearranged to solve it for cos²φ, this identity states that cos²φ = 1 – sin²φ. Using this rearranged identity to make substitutions on both sides of the previous equation Ml²cos²λ = Mr²cos²ρ yields the new equation Ml²(1 – sin²λ) = Mr²(1 – sin²ρ). Applying the distributive property yields the equation Ml² – Ml²sin²λ = Mr² – Mr²sin²ρ. By addition, this then becomes -Ml²sin²λ = Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ. Solving this for sin²λ turns it into sin²λ = (Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ)/(-Ml²).

Next, Mc = Mlsinλ + Mrsinρ (the simplied version of the vertical-force-balance equation, from above), when solved for sinλ, becomes sinλ = (Mrsinρ – Mc)/(- Ml). Squaring both sides of this equation turns it into sin²λ = (Mr²sin²ρ – 2MrMcsinρ + Mc²)/(- Ml)².

There are now two equations solved for sin²λ, each shown in bold at the end of one of the previous two paragraphs. Setting the two expressions shown equal to sin²λ equal to each other yields the new equation (Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ)/(-Ml²) = (Mr²sin²ρ – 2MrMcsinρ + Mc²)/(- Ml)², which then becomes (Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ)/(-Ml²) = (Mr²sin²ρ – 2MrMcsinρ + Mc²)/(Ml)², and then, by multiplying both sides by -Ml², this simplifies to Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ = – (Mr²sin²ρ – 2MrMcsinρ + Mc²), and then Mr² – Ml² – Mr²sin²ρ = – Mr²sin²ρ + 2MrMcsinρ – Mc². Since this equation has the term – Mr²sin²ρ on both sides, cancelling it simplifies this to Mr² – Ml² = 2MrMcsinρ – Mc², which then becomes Mr² – Ml² + Mc² = 2MrMcsinρ, and then sinρ = (Mr² – Ml² + Mc²)/2MrMc = [(0.150 kg)² – (0.100 kg)² + (0.170 kg)²]/[2(0.150 kg)(0.170 kg)] = (0.0225 – 0.0100 + 0.0289)/0.0510 = 0.0414/0.510 = 0.812. The inverse sine of this value gives us ρ = 54°.

Having one angle’s measure, of course, makes it far easier to find the others. Two paragraphs up, an equation in italics stated that sinλ = (Mrsinρ – Mc)/(- Ml). It follows that λ = sin-1[(Mrsinρ – Mc)/(- Ml)] = sin-1[(0.150kg)sinρ – 0.170kg)/(-0.100kg)] = 29°. These two angles sum to 83°, leaving 180° – 83° = 97° as the value of θ.

As can be seen above, these derived values are close to demonstrated experimental values. The first angle found, ρ, measures ~58°, which differs from the theoretical value of 54° by approximately 7%. The next, λ, measures ~31°, also differing from the theoretical value, 29°, by about 7%.The experimental value for θ is (180 – 58 – 31)° = 91°, which is off from the theoretical value of 97° by ~6%. All of these errors are smaller than the 9% error found for both λ and ρ in the easier, symmetrical version of this problem, and the causes of this error should be the same as before.

Before an undertaking as great as building a Dyson Sphere, it’s a good idea to plan ahead first. This rotating image shows what my plan for an enneagonal-antiprism-based Dyson Sphere looked like, at the hemisphere stage. At this point, the best I could hope for is was three-fold dihedral symmetry.

I didn’t get what I was hoping for, but only ended up with plain old three-fold polar symmetry, once my Dyson Sphere plan got at far as it could go without the unit enneagonal antiprisms running into each other. Polyhedra-obsessives tend to also be symmetry-obsessives, and this just isn’t good enough for me.

If we filled in the gaps by creating the convex hull of the above complex of enneagonal antiprisms, in order to capture all the sun’s energy (and make our Dyson Sphere harder to see from outside it), here’s what this would look like, in false color (the real thing would be black) — and the convex hull of this Dyson Sphere design, in my opinion, especially when colored by number of sides per face, really reveals how bad an idea it would be to build our Dyson sphere in this way.

We could find ourselves laughed out of the Galactic Alliance if we built such a low-order-of-symmetry Dyson Sphere — so, please, don’t do it. On the other hand, please also stay away from geodesic spheres or their duals, the polyhedra which resemble fullerenes, for we certainly don’t want our Dyson Sphere looking like all the rest of them. We need to find something better, before construction begins. Perhaps a snub dodecahedron? But, if we use a chiral polyhedron, how do we decide which enantiomer to use?

[All three images of my not-good-enough Dyson Sphere plan were created using Stella 4d, which you can get for yourself at this website.]

Because there’s nothing wrong with mixing a little Rolling Stones with your physics, that’s why.

Since I like spiders, I was pleased to read a rough estimate of 21 quadrillion for the world’s population of spiders (source: here).

The website http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ gives the current human population as ~7.4 billion. Dividing the estimated spider population by the estimated human population yields Earth’s estimated spider-to-human ratio: 2.8 million.

Yes, your share approaches three million spiders. At least they are good at taking care of themselves!

[Source of the image of the spider above, an adult male phidippus audax: https://www.flickr.com/photos/opoterser/2989573241]

The last workweek having left me rather tired, I went to bed early Friday, after work, and then, having slept all I could sleep, I then woke back up quite early Saturday morning, before sunrise, and couldn’t get back to sleep. I was tired all day Saturday, but not too weary to think. What I thought was simple: as tired as I am, it sure would be nice to have a three-day weekend this weekend. Next, I thought, yeah, this would be nice, but that won’t make it happen. Finally, I realized that I actually could, perhaps, come up with some hopefully-clever and effective way to get the three-day weekend I want . . . and, having had an idea to do exactly that, I’m trying it right now.

I’ve tested the 24-hour sleep/wake cycle before, trying to find ways to lengthen that period of time. (Ever wanted more hours in the day? Well, I actually tried to make that happen, once, but the results were less than successful.) This time, however, I’m not trying to get extra hours in a day, but an extra day in the weekend — by simply using shorter “days,” and thus making “room,” temporally, to add an extra sleep-period and wake-period into the weekend. So, Friday, I fell asleep around 5:00 pm, and did so without the prescribed medication (which includes sedatives) which I usually take at bedtime, since it wasn’t that late yet . . . so I simply fell asleep because I was tired.

Without the sedatives I am used to taking, of course, I didn’t stay asleep anything like a full eight hours, and instead “popped” back awake at around 9 pm, which was less than an hour ago, as I write this. Rather than sedating and returning to sleep, however, I took the other medication I am prescribed for this time of the day (such as that needed to regulate blood pressure), and then made my “morning” coffee, which I am enjoying now . . . to begin the extra “day” I’m attempting to add to this weekend, between Saturday and Sunday. My hypothesis is that I can deliberately alter my sleep/wake cycle in such a way that I have three (shorter) sleep/wake cycles in two calendar days, thus giving myself a three-day weekend, of a sort, and enjoy the benefits of a three-day weekend as a result. If, come Monday, I feel like I’ve had a three-day weekend — in that I feel unusually well-rested — I will consider this experiment to “create” a working illusion of a three-day weekend, without any actual extra time, to be a success (subject to the opinion of my doctors, to whom I will describe all of this).

I plan to stay awake until roughly dawn on Sunday, and then go to sleep until, well, whenever I wake up. I’ll then have a shortened post-sleep Sunday wakefulness-period, go to sleep at a reasonable hour Sunday night, and get a good, full night’s sleep then, before going to work on Monday.

Right now, therefore, I’m having the middle “day” of what feels, subjectively, like a three-day weekend, and having it at night, between what seems, now, like it was yesterday (the shortened Saturday), and what I anticipate as my shortened Sunday, after I sleep again, tomorrow. Since it’s easier to talk about this extra “day” I’m having tonight if I give it a name, I’m doing so: I’m calling it “Nightday.”

Some readers may object that I’ve merely come up with an overly-convoluted way to analyze a four-hour Saturday-afternoon nap. I’ll concede that they do have a point . . . but if my calling this “Nightday,” and telling myself that I’m enjoying a three-day weekend, actually turns out to help me feel and act more rested next week, then I’ll take those benefits and run with them, regardless of what any critics tell me (unless, of course, my doctors are among those critics). If this experiment has only beneficial results, and passes medical review, then I’ll likely use more Nightdays to get additional three-day weekends in the future, whenever I need, or simply want, them.

~~~

Important disclaimer: nothing in this blog-post should be taken as any form of medical advice, for I am not medically trained. I have taken the precaution of discussing my practice of occasionally inventing and conducting experiments such as this with my own physicians, and will continue to do so. No one should attempt to replicate this experiment without first consulting their own physician(s).

[Image credit: the photo of the Moon shown above was found here — https://photographylife.com/moon-waning-gibbous. It isn’t identical in appearance to the current waning gibbous Moon, having been photographed quite some time earlier, but it is close.]

In the Summer of 2014, with many other science teachers, I took a four-day-long A.P. Physics training session, which was definitely a valuable experience, for me, as a teacher. On the last day of this training, though, in the late afternoon, as the trainer and trainees were winding things up, some of us, including me, started getting a little silly. Physics teachers, of course, have their own version of silly behavior. Here’s what happened.

The trainer: “Let’s see how well you understand the different forces which can serve as centripetal forces, in different situations. When I twirl a ball, on a string, in a horizontal circle, what is the centripetal force?”

The class of trainees, in unison: “Tension!”

Trainer: “In the Bohr model of a hydrogen atom, the force keeping the electron traveling in a circle around the proton is the . . . ?”

Class: “Electromagnetic force!”

Trainer: “What force serves as the centripetal force keeping the Earth in orbit around the Sun?”

Me, loudly, before any of my classmates could answer: “God’s will!”

I was, remember, surrounded by physics teachers. It took the trainer several minutes to restore order, after that.